Algebra, Sequences

A sequence is an ordered list of numbers (or other items) that often follows a specific rule or pattern. This topic covers identifying patterns, finding specific terms, determining general formulas (`n`-th term), and understanding different types of sequences (arithmetic, geometric, recursive).

Arithmetic Progression / Arithmetic Sequence Complete/Continue the Sequence Recurrence Relations-

50 to the Power of

Show that in the rightmost 504 digits of `1+50+50^2+...+50^1000`

Each digit appears a number of times divisible by 12

Sources: -

Question

By what factor is the sum of all numbers from 1 to 99 smaller than the sum of all numbers from 1 to 9999?

Sources:Topics:Algebra -> Sequences -> Arithmetic Progression / Arithmetic Sequence -

Divisible by 13

All natural numbers from 1 to 2006 are written on a sheet of paper, and a series of operations is performed as described below. At each step, any number of numbers are deleted from the list and their sum is denoted by S. Instead of the deleted numbers, a single number is added, which is the remainder obtained from the division of S by 13. After some number of such steps, only two numbers remain on the paper. One of them is 100. Find the other number.

Sources:Topics:Number Theory -> Modular Arithmetic / Remainder Arithmetic Number Theory -> Division -> Parity (Even/Odd) Algebra -> Sequences -> Arithmetic Progression / Arithmetic Sequence- Grossman Math Olympiad, 2006 Question 2

-

Maximum Length Game

The game begins with a row of 42 coins, all showing 'Heads' up.

Each player, in their turn, chooses one of the coins showing 'Heads' up - flips the chosen coin, and also the coin immediately to its right (if one exists).

If you manage to make all the coins show 'Tails' up on your turn, you win the game!

At most, after how many turns will the game end?

Sources:Topics:Algebra -> Sequences -> Arithmetic Progression / Arithmetic Sequence -

THE BASKET OF POTATOES

A man had a basket containing fifty potatoes. He proposed to his son, as a little recreation, that he should place these potatoes on the ground in a straight line. The distance between the first and second potatoes was to be one yard, between the second and third three yards, between the third and fourth five yards, between the fourth and fifth seven yards, and so on—an increase of two yards for every successive potato laid down. Then the boy was to pick them up and put them in the basket one at a time, the basket being placed beside the first potato. How far would the boy have to travel to accomplish the feat of picking them all up? We will not consider the journey involved in placing the potatoes, so that he starts from the basket with them all laid out.Sources:Topics:Algebra -> Word Problems Algebra -> Sequences -> Arithmetic Progression / Arithmetic Sequence- Amusements in Mathematics, Henry Ernest Dudeney Question 74

-

THE THIRTY-THREE PEARLS

"A man I know," said Teddy Nicholson at a certain family party, "possesses a string of thirty-three pearls. The middle pearl is the largest and best of all, and the others are so selected and arranged that, starting from one end, each successive pearl is worth £`100` more than the preceding one, right up to the big pearl. From the other end the pearls increase in value by £`150` up to the large pearl. The whole string is worth £`65,000`. What is the value of that large pearl?"

"Pearls and other articles of clothing," said Uncle Walter, when the price of the precious gem had been discovered, "remind me of Adam and Eve. Authorities, you may not know, differ as to the number of apples that were eaten by Adam and Eve. It is the opinion of some that Eve `8` (ate) and Adam `2` (too), a total of `10` only. But certain mathematicians have figured it out differently, and hold that Eve `8` and Adam a total of `16`. Yet the most recent investigators think the above figures entirely wrong, for if Eve `8` and Adam `82`, the total must be `90`."

"Well," said Harry, "it seems to me that if there were giants in those days, probably Eve `81` and Adam `82`, which would give a total of `163`."

"I am not at all satisfied," said Maud. "It seems to me that if Eve `81` and Adam `812`, they together consumed `893`."

"I am sure you are all wrong," insisted Mr. Wilson, "for I consider that Eve `814` Adam, and Adam `8124` Eve, so we get a total of `8,938`."

"But, look here," broke in Herbert. "If Eve `814` Adam and Adam `81242` oblige Eve, surely the total must have been `82,056`!"

At this point Uncle Walter suggested that they might let the matter rest. He declared it to be clearly what mathematicians call an indeterminate problem.

Sources:Topics:Arithmetic Algebra -> Equations Algebra -> Word Problems Algebra -> Sequences -> Arithmetic Progression / Arithmetic Sequence- Amusements in Mathematics, Henry Ernest Dudeney Question 99

-

A PROBLEM IN SQUARES

We possess three square boards. The surface of the first contains five square feet more than the second, and the second contains five square feet more than the third. Can you give exact measurements for the sides of the boards? If you can solve this little puzzle, then try to find three squares in arithmetical progression, with a common difference of `7` and also of `13`.Sources:Topics:Number Theory Algebra -> Sequences -> Arithmetic Progression / Arithmetic Sequence Algebra -> Equations -> Diophantine Equations- Amusements in Mathematics, Henry Ernest Dudeney Question 128

-

THE NINE TREASURE BOXES

The following puzzle will illustrate the importance on occasions of being able to fix the minimum and maximum limits of a required number. This can very frequently be done. For example, it has not yet been ascertained in how many different ways the knight's tour can be performed on the chess board; but we know that it is fewer than the number of combinations of `168` things taken `63` at a time and is greater than `31,054,144`—for the latter is the number of routes of a particular type. Or, to take a more familiar case, if you ask a man how many coins he has in his pocket, he may tell you that he has not the slightest idea. But on further questioning you will get out of him some such statement as the following: "Yes, I am positive that I have more than three coins, and equally certain that there are not so many as twenty-five." Now, the knowledge that a certain number lies between `2` and `12` in my puzzle will enable the solver to find the exact answer; without that information there would be an infinite number of answers, from which it would be impossible to select the correct one.

This is another puzzle received from my friend Don Manuel Rodriguez, the cranky miser of New Castile. On New Year's Eve in `1879` he showed me nine treasure boxes, and after informing me that every box contained a square number of golden doubloons, and that the difference between the contents of A and B was the same as between B and C, D and E, E and F, G and H, or H and I, he requested me to tell him the number of coins in every one of the boxes. At first I thought this was impossible, as there would be an infinite number of different answers, but on consideration I found that this was not the case. I discovered that while every box contained coins, the contents of A, B, C increased in weight in alphabetical order; so did D, E, F; and so did G, H, I; but D or E need not be heavier than C, nor G or H heavier than F. It was also perfectly certain that box A could not contain more than a dozen coins at the outside; there might not be half that number, but I was positive that there were not more than twelve. With this knowledge I was able to arrive at the correct answer.

In short, we have to discover nine square numbers such that A, B, C; and D, E, F; and G, H, I are three groups in arithmetical progression, the common difference being the same in each group, and A being less than `12`. How many doubloons were there in every one of the nine boxes?

Sources:Topics:Number Theory Algebra -> Sequences -> Arithmetic Progression / Arithmetic Sequence Algebra -> Equations -> Diophantine Equations- Amusements in Mathematics, Henry Ernest Dudeney Question 132

-

THE FIVE BRIGANDS

The five Spanish brigands, Alfonso, Benito, Carlos, Diego, and Esteban, were counting their spoils after a raid, when it was found that they had captured altogether exactly `200` doubloons. One of the band pointed out that if Alfonso had twelve times as much, Benito three times as much, Carlos the same amount, Diego half as much, and Esteban one-third as much, they would still have altogether just `200` doubloons. How many doubloons had each?

There are a good many equally correct answers to this question. Here is one of them:

A 6 × 12 = 72 B 12 × 3 = 36 C 17 × 1 = 17 D 120 × ½ = 60 E 45 × 1/3 = 15 200 200 The puzzle is to discover exactly how many different answers there are, it being understood that every man had something and that there is to be no fractional money—only doubloons in every case.

This problem, worded somewhat differently, was propounded by Tartaglia (died `1559`), and he flattered himself that he had found one solution; but a French mathematician of note (M.A. Labosne), in a recent work, says that his readers will be astonished when he assures them that there are `6,639` different correct answers to the question. Is this so? How many answers are there?

Sources:Topics:Number Theory Arithmetic Algebra -> Word Problems Algebra -> Sequences -> Arithmetic Progression / Arithmetic Sequence Combinatorics -> Case Analysis / Checking Cases -> Processes / Procedures Algebra -> Equations -> Diophantine Equations- Amusements in Mathematics, Henry Ernest Dudeney Question 133

-

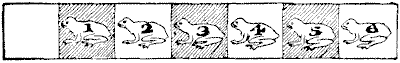

THE SIX FROGS

The six educated frogs in the illustration are trained to reverse their order, so that their numbers shall read `6, 5, 4, 3, 2, 1`, with the blank square in its present position. They can jump to the next square (if vacant) or leap over one frog to the next square beyond (if vacant), just as we move in the game of draughts, and can go backwards or forwards at pleasure. Can you show how they perform their feat in the fewest possible moves? It is quite easy, so when you have done it add a seventh frog to the right and try again. Then add more frogs until you are able to give the shortest solution for any number. For it can always be done, with that single vacant square, no matter how many frogs there are.

Sources:Topics:Algebra -> Sequences -> Arithmetic Progression / Arithmetic Sequence

The six educated frogs in the illustration are trained to reverse their order, so that their numbers shall read `6, 5, 4, 3, 2, 1`, with the blank square in its present position. They can jump to the next square (if vacant) or leap over one frog to the next square beyond (if vacant), just as we move in the game of draughts, and can go backwards or forwards at pleasure. Can you show how they perform their feat in the fewest possible moves? It is quite easy, so when you have done it add a seventh frog to the right and try again. Then add more frogs until you are able to give the shortest solution for any number. For it can always be done, with that single vacant square, no matter how many frogs there are.

Sources:Topics:Algebra -> Sequences -> Arithmetic Progression / Arithmetic Sequence- Amusements in Mathematics, Henry Ernest Dudeney Question 214