Algebra, Sequences

A sequence is an ordered list of numbers (or other items) that often follows a specific rule or pattern. This topic covers identifying patterns, finding specific terms, determining general formulas (`n`-th term), and understanding different types of sequences (arithmetic, geometric, recursive).

Arithmetic Progression / Arithmetic Sequence Complete/Continue the Sequence Recurrence Relations-

The Confrontation

Ehud and Benjamin are participating in a public confrontation. Each presents, in turn, a question to their opponent. Ehud is chosen to be the first to present a question. A "tricky question" is a question for which the opponent has no answer. A contestant who manages to ask a tricky question immediately wins the confrontation. The probability of each of the two contestants finding (in turn) a tricky question is exactly 1/2. It is also known that there is no dependence between the questions. What is the probability of Ehud winning the confrontation?

-

The Confrontation

Ehud and Benjamin are participating in a public debate. Each one presents a question to his opponent in turn. Ehud is chosen to be the first to present a question. A "tricky question" is a question that the opponent has no answer to. A contestant who manages to ask a tricky question immediately wins the debate. The probability of each of the two contestants finding (in turn) a tricky question is exactly 1/2. Also, it is known that there is no dependence between the questions. What is the probability of Ehud winning the debate?

Sources:- Grossman Math Olympiad, 2006 Question 1

-

The 1224th Digit

We write the natural numbers in order, one after the other from left to right:

1234567891011...

Note, for example, that the digit in the 10th place is 1 and the digit in the 11th place is 0.

Continuing with this writing as much as needed...

Which digit will be in the 1224th place in the sequence?

Sources: -

Question

The numbers from 1 to `10^9` (inclusive) are written on the board. The numbers divisible by 3 are written in red, and the rest of the numbers are written in blue. The sum of all the red numbers is equal to `X`, and the sum of all the blue numbers is equal to `Y`. Which number is larger, `2X` or `Y`, and by how much?

Sources:Topics:Arithmetic Number Theory -> Modular Arithmetic / Remainder Arithmetic -> Divisibility Rules -> Divisibility Rules by 3 and 9 Logic -> Reasoning / Logic Algebra -> Sequences Algebra -> Inequalities -> Averages / Means Number Theory -> Division- Beno Arbel Olympiad, 2017, Grade 8 Question 2

-

A QUEER COINCIDENCE

Seven men, whose names were Adams, Baker, Carter, Dobson, Edwards, Francis, and Gudgeon, were recently engaged in play. The name of the particular game is of no consequence. They had agreed that whenever a player won a game he should double the money of each of the other players—that is, he was to give the players just as much money as they had already in their pockets. They played seven games, and, strange to say, each won a game in turn, in the order in which their names are given. But a more curious coincidence is this—that when they had finished play each of the seven men had exactly the same amount—two shillings and eightpence—in his pocket. The puzzle is to find out how much money each man had with him before he sat down to play. Sources: -

CURIOUS NUMBERS

The number `48` has this peculiarity, that if you add `1` to it the result is a square number (`49`, the square of `7`), and if you add `1` to its half, you also get a square number (`25`, the square of `5`). Now, there is no limit to the numbers that have this peculiarity, and it is an interesting puzzle to find three more of them—the smallest possible numbers. What are they? Sources:- Amusements in Mathematics, Henry Ernest Dudeney Question 114

-

THE STONEMASON'S PROBLEM

A stonemason once had a large number of cubic blocks of stone in his yard, all of exactly the same size. He had some very fanciful little ways, and one of his queer notions was to keep these blocks piled in cubical heaps, no two heaps containing the same number of blocks. He had discovered for himself (a fact that is well known to mathematicians) that if he took all the blocks contained in any number of heaps in regular order, beginning with the single cube, he could always arrange those on the ground so as to form a perfect square. This will be clear to the reader, because one block is a square, `1+8 = 9` is a square, `1+8+27=36` is a square, `1+8+27+64=100` is a square, and so on. In fact, the sum of any number of consecutive cubes, beginning always with `1`, is in every case a square number.

One day a gentleman entered the mason's yard and offered him a certain price if he would supply him with a consecutive number of these cubical heaps which should contain altogether a number of blocks that could be laid out to form a square, but the buyer insisted on more than three heaps and declined to take the single block because it contained a flaw. What was the smallest possible number of blocks of stone that the mason had to supply?

Sources:- Amusements in Mathematics, Henry Ernest Dudeney Question 135

-

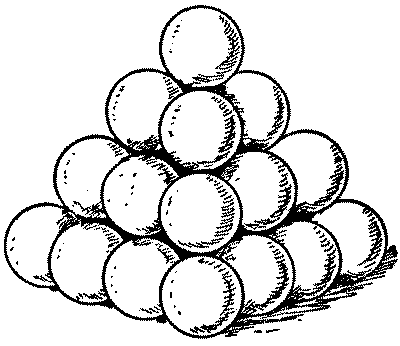

THE ARTILLERYMEN'S DILEMMA

"All cannon-balls are to be piled in square pyramids," was the order issued to the regiment. This was done. Then came the further order, "All pyramids are to contain a square number of balls." Whereupon the trouble arose. "It can't be done," said the major. "Look at this pyramid, for example; there are sixteen balls at the base, then nine, then four, then one at the top, making thirty balls in all. But there must be six more balls, or five fewer, to make a square number." "It must be done," insisted the general. "All you have to do is to put the right number of balls in your pyramids." "I've got it!" said a lieutenant, the mathematical genius of the regiment. "Lay the balls out singly." "Bosh!" exclaimed the general. "You can't pile one ball into a pyramid!" Is it really possible to obey both orders?

Sources:

"All cannon-balls are to be piled in square pyramids," was the order issued to the regiment. This was done. Then came the further order, "All pyramids are to contain a square number of balls." Whereupon the trouble arose. "It can't be done," said the major. "Look at this pyramid, for example; there are sixteen balls at the base, then nine, then four, then one at the top, making thirty balls in all. But there must be six more balls, or five fewer, to make a square number." "It must be done," insisted the general. "All you have to do is to put the right number of balls in your pyramids." "I've got it!" said a lieutenant, the mathematical genius of the regiment. "Lay the balls out singly." "Bosh!" exclaimed the general. "You can't pile one ball into a pyramid!" Is it really possible to obey both orders?

Sources:

- Amusements in Mathematics, Henry Ernest Dudeney Question 138

-

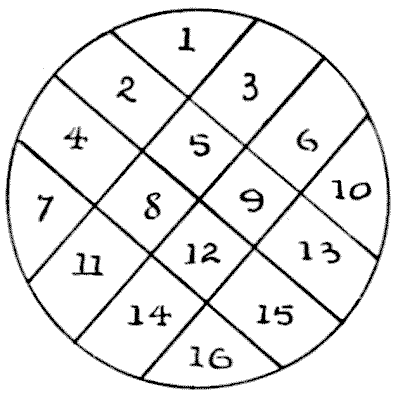

THE POTATO PUZZLE

Take a circular slice of potato, place it on the table, and see into how large a number of pieces you can divide it with six cuts of a knife. Of course you must not readjust the pieces or pile them after a cut. What is the greatest number of pieces you can make? The illustration shows how to make sixteen pieces. This can, of course, be easily beaten.

Sources:Topics:Geometry -> Plane Geometry Algebra -> Sequences Combinatorics -> Combinatorial Geometry -> Cut a Shape / Dissection Problems

The illustration shows how to make sixteen pieces. This can, of course, be easily beaten.

Sources:Topics:Geometry -> Plane Geometry Algebra -> Sequences Combinatorics -> Combinatorial Geometry -> Cut a Shape / Dissection Problems- Amusements in Mathematics, Henry Ernest Dudeney Question 164

-

SUCH A GETTING UPSTAIRS

In a suburban villa there is a small staircase with eight steps, not counting the landing. The little puzzle with which Tommy Smart perplexed his family is this. You are required to start from the bottom and land twice on the floor above (stopping there at the finish), having returned once to the ground floor. But you must be careful to use every tread the same number of times. In how few steps can you make the ascent? It seems a very simple matter, but it is more than likely that at your first attempt you will make a great many more steps than are necessary. Of course you must not go more than one riser at a time.

Tommy knows the trick, and has shown it to his father, who professes to have a contempt for such things; but when the children are in bed the pater will often take friends out into the hall and enjoy a good laugh at their bewilderment. And yet it is all so very simple when you know how it is done.

Sources:- Amusements in Mathematics, Henry Ernest Dudeney Question 418