Number Theory

Number Theory is a branch of mathematics concerned with the properties of integers. Topics include prime numbers, divisibility, congruences (modular arithmetic), Diophantine equations, and functions of integers. Questions often require analytical and creative thinking about numbers.

Prime Numbers Chinese Remainder Theorem Modular Arithmetic / Remainder Arithmetic Greatest Common Divisor (GCD) and Least Common Multiple (LCM) Triangular Numbers Division-

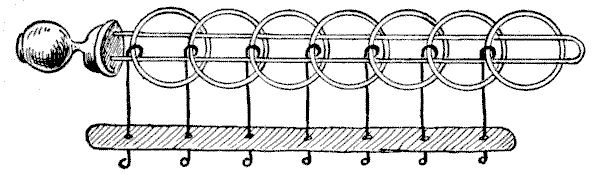

THE TIRING IRONS

The illustration represents one of the most ancient of all mechanical puzzles. Its origin is unknown. Cardan, the mathematician, wrote about it in `1550`, and Wallis in `1693`; while it is said still to be found in obscure English villages (sometimes deposited in strange places, such as a church belfry), made of iron, and appropriately called "tiring-irons," and to be used by the Norwegians to-day as a lock for boxes and bags. In the toyshops it is sometimes called the "Chinese rings," though there seems to be no authority for the description, and it more frequently goes by the unsatisfactory name of "the puzzling rings." The French call it "Baguenaudier."

The puzzle will be seen to consist of a simple loop of wire fixed in a handle to be held in the left hand, and a certain number of rings secured by wires which pass through holes in the bar and are kept there by their blunted ends. The wires work freely in the bar, but cannot come apart from it, nor can the wires be removed from the rings. The general puzzle is to detach the loop completely from all the rings, and then to put them all on again.

Now, it will be seen at a glance that the first ring (to the right) can be taken off at any time by sliding it over the end and dropping it through the loop; or it may be put on by reversing the operation. With this exception, the only ring that can ever be removed is the one that happens to be a contiguous second on the loop at the right-hand end. Thus, with all the rings on, the second can be dropped at once; with the first ring down, you cannot drop the second, but may remove the third; with the first three rings down, you cannot drop the fourth, but may remove the fifth; and so on. It will be found that the first and second rings can be dropped together or put on together; but to prevent confusion we will throughout disallow this exceptional double move, and say that only one ring may be put on or removed at a time.

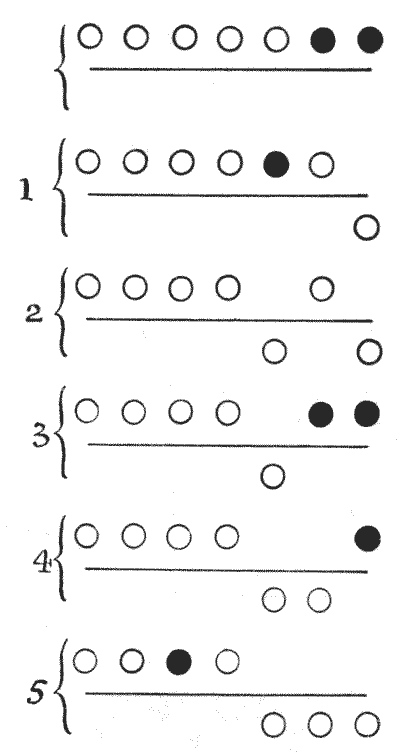

We can thus take off one ring in `1` move; two rings in `2` moves; three rings in `5` moves; four rings in `10` moves; five rings in `21` moves; and if we keep on doubling (and adding one where the number of rings is odd) we may easily ascertain the number of moves for completely removing any number of rings. To get off all the seven rings requires `85` moves. Let us look at the five moves made in removing the first three rings, the circles above the line standing for rings on the loop and those under for rings off the loop.

Drop the first ring; drop the third; put up the first; drop the second; and drop the first—`5` moves, as shown clearly in the diagrams. The dark circles show at each stage, from the starting position to the finish, which rings it is possible to drop. After move `2` it will be noticed that no ring can be dropped until one has been put on, because the first and second rings from the right now on the loop are not together. After the fifth move, if we wish to remove all seven rings we must now drop the fifth. But before we can then remove the fourth it is necessary to put on the first three and remove the first two. We shall then have `7, 6, 4, 3` on the loop, and may therefore drop the fourth. When we have put on `2` and `1` and removed `3, 2, 1`, we may drop the seventh ring. The next operation then will be to get `6, 5, 4, 3, 2, 1` on the loop and remove `4, 3, 2, 1`, when `6` will come off; then get `5, 4, 3, 2, 1` on the loop, and remove `3, 2, 1`, when `5` will come off; then get `4, 3, 2, 1` on the loop and remove `2, 1`, when `4` will come off; then get `3, 2, 1` on the loop and remove `1`, when `3` will come off; then get `2, 1` on the loop, when `2` will come off; and `1` will fall through on the 85th move, leaving the loop quite free. The reader should now be able to understand the puzzle, whether or not he has it in his hand in a practical form.

The particular problem I propose is simply this. Suppose there are altogether fourteen rings on the tiring-irons, and we proceed to take them all off in the correct way so as not to waste any moves. What will be the position of the rings after the `9`,999th move has been made?

Sources:Topics:Arithmetic Number Theory -> Division -> Parity (Even/Odd) Algebra -> Sequences -> Recurrence Relations Combinatorics -> Case Analysis / Checking Cases -> Processes / Procedures Combinatorics -> Case Analysis / Checking Cases -> Processes / Procedures- Amusements in Mathematics, Henry Ernest Dudeney Question 417

-

Question

There are chairs with `4` legs and with `3` legs in a room. When people sat on all the chairs, there were `39` legs in the room (no one remained standing). How many chairs of each type are there in the room?

-

Question

In the magical land, there are only two types of coins: `16` LC (Magical Pounds) and `27` LC. Is it possible to buy a notebook that costs one Magical Pound and receive exact change?

-

SIMPLE DIVISION

Sometimes a very simple question in elementary arithmetic will cause a good deal of perplexity. For example, I want to divide the four numbers, `701, 1,059, 1,417`, and `2,312`, by the largest number possible that will leave the same remainder in every case. How am I to set to work Of course, by a laborious system of trial one can in time discover the answer, but there is quite a simple method of doing it if you can only find it.Sources:Topics:Arithmetic Number Theory -> Greatest Common Divisor (GCD) and Least Common Multiple (LCM) -> Euclidean Algorithm Number Theory -> Division- Amusements in Mathematics, Henry Ernest Dudeney Question 127

-

Question

a. Prove that among `11` natural numbers, it is always possible to choose two such that their units digit is the same.

b. Prove that among `11` natural numbers, it is always possible to choose two such that their difference is divisible by `10`.

-

Question

Find all integer solutions `(k>1) y^k=x^2+x`

Sources:Topics:Number Theory -> Prime Numbers -> Prime Factorization Number Theory -> Greatest Common Divisor (GCD) and Least Common Multiple (LCM) Algebra -> Equations -> Diophantine Equations- Tournament of Towns, 1980-1981, Spring, Main Version, Grades 9-10 Question 1 Points 3

-

Question

Represent the number `203` as the product of several natural numbers different from `203`, such that the sum of these numbers is also equal to `203`.

Sources:Topics:Number Theory -> Prime Numbers -> Prime Factorization -

Question

It is known that every prime number has two divisors – `1` and the number itself. What numbers have exactly three divisors?

Sources:Topics:Number Theory -> Prime Numbers -> Prime Factorization -

Question

How many solutions in natural numbers are there to the equation `(2013 - x)(2013-y)=2013^2`?

Sources:Topics:Number Theory -> Prime Numbers -> Prime Factorization Algebra -> Equations -> Diophantine Equations- Beno Arbel Olympiad, 2013, Grade 7 Question 6

-

Question

Does there exist a natural number such that the product of its digits is equal to `99`?

Topics:Number Theory -> Prime Numbers -> Prime Factorization