Number Theory

Number Theory is a branch of mathematics concerned with the properties of integers. Topics include prime numbers, divisibility, congruences (modular arithmetic), Diophantine equations, and functions of integers. Questions often require analytical and creative thinking about numbers.

Prime Numbers Chinese Remainder Theorem Modular Arithmetic / Remainder Arithmetic Greatest Common Divisor (GCD) and Least Common Multiple (LCM) Triangular Numbers Division-

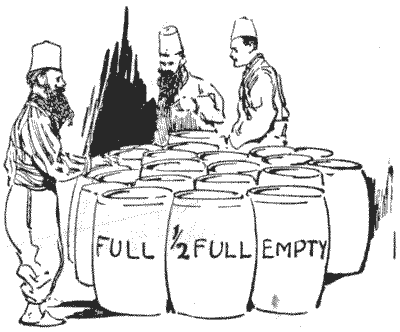

THE BARRELS OF HONEY

Once upon a time there was an aged merchant of Bagdad who was much respected by all who knew him. He had three sons, and it was a rule of his life to treat them all exactly alike. Whenever one received a present, the other two were each given one of equal value. One day this worthy man fell sick and died, bequeathing all his possessions to his three sons in equal shares.

The only difficulty that arose was over the stock of honey. There were exactly twenty-one barrels. The old man had left instructions that not only should every son receive an equal quantity of honey, but should receive exactly the same number of barrels, and that no honey should be transferred from barrel to barrel on account of the waste involved. Now, as seven of these barrels were full of honey, seven were half-full, and seven were empty, this was found to be quite a puzzle, especially as each brother objected to taking more than four barrels of, the same description—full, half-full, or empty. Can you show how they succeeded in making a correct division of the property?

Sources:Topics:Algebra -> Word Problems Arithmetic -> Fractions Combinatorics -> Case Analysis / Checking Cases -> Processes / Procedures Number Theory -> Division- Amusements in Mathematics, Henry Ernest Dudeney Question 372

-

Question

`120` identical spheres are arranged in the shape of a triangular pyramid. How many layers are there in the pyramid?

Note: This is a pyramid, which is a three-dimensional shape, and not a triangle in a plane.

Topics:Geometry -> Solid Geometry / Geometry in Space Arithmetic Logic -> Reasoning / Logic Proof and Example -> Constructing an Example / Counterexample Algebra -> Sequences -> Arithmetic Progression / Arithmetic Sequence Algebra -> Sequences -> Complete/Continue the Sequence Number Theory -> Triangular Numbers -

A STUDY IN THRIFT

Certain numbers are called triangular, because if they are taken to represent counters or coins they may be laid out on the table so as to form triangles. The number `1` is always regarded as triangular, just as `1` is a square and a cube number. Place one counter on the table—that is, the first triangular number. Now place two more counters beneath it, and you have a triangle of three counters; therefore `3` is triangular. Next place a row of three more counters, and you have a triangle of six counters; therefore `6` is triangular. We see that every row of counters that we add, containing just one more counter than the row above it, makes a larger triangle.

Now, half the sum of any number and its square is always a triangular number. Thus half of `2` + `2``2` = `3`; half of `3` + `3``2` = `6`; half of `4 + 4``2` = `10`; half of `5` + `5``2`= `15`; and so on. So if we want to form a triangle with `8` counters on each side we shall require half of `8 + 8``2`, or `36` counters. This is a pretty little property of numbers. Before going further, I will here say that if the reader refers to the "Stonemason's Problem" (No. `135`) he will remember that the sum of any number of consecutive cubes beginning with `1` is always a square, and these form the series `1``2`, `3``2`, `6``2`, `10``2`, etc. It will now be understood when I say that one of the keys to the puzzle was the fact that these are always the squares of triangular numbers—that is, the squares of `1, 3, 6, 10, 15, 21, 28`, etc., any of which numbers we have seen will form a triangle.

Every whole number is either triangular, or the sum of two triangular numbers or the sum of three triangular numbers. That is, if we take any number we choose we can always form one, two, or three triangles with them. The number `1` will obviously, and uniquely, only form one triangle; some numbers will only form two triangles (as `2, 4, 11`, etc.); some numbers will only form three triangles (as `5, 8, 14`, etc.). Then, again, some numbers will form both one and two triangles (as `6`), others both one and three triangles (as `3` and `10`), others both two and three triangles (as `7` and `9`), while some numbers (like `21`) will form one, two, or three triangles, as we desire. Now for a little puzzle in triangular numbers.

Sandy McAllister, of Aberdeen, practised strict domestic economy, and was anxious to train his good wife in his own habits of thrift. He told her last New Year's Eve that when she had saved so many sovereigns that she could lay them all out on the table so as to form a perfect square, or a perfect triangle, or two triangles, or three triangles, just as he might choose to ask he would add five pounds to her treasure. Soon she went to her husband with a little bag of £`36` in sovereigns and claimed her reward. It will be found that the thirty-six coins will form a square (with side `6`), that they will form a single triangle (with side `8`), that they will form two triangles (with sides `5` and `6`), and that they will form three triangles (with sides `3, 5`, and `5`). In each of the four cases all the thirty-six coins are used, as required, and Sandy therefore made his wife the promised present like an honest man.

The Scotsman then undertook to extend his promise for five more years, so that if next year the increased number of sovereigns that she has saved can be laid out in the same four different ways she will receive a second present; if she succeeds in the following year she will get a third present, and so on until she has earned six presents in all. Now, how many sovereigns must she put together before she can win the sixth present?

What you have to do is to find five numbers, the smallest possible, higher than `36`, that can be displayed in the four ways—to form a square, to form a triangle, to form two triangles, and to form three triangles. The highest of your five numbers will be your answer.

Sources:Topics:Number Theory -> Triangular Numbers- Amusements in Mathematics, Henry Ernest Dudeney Question 137

-

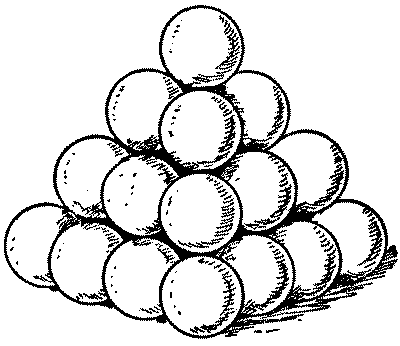

THE ARTILLERYMEN'S DILEMMA

"All cannon-balls are to be piled in square pyramids," was the order issued to the regiment. This was done. Then came the further order, "All pyramids are to contain a square number of balls." Whereupon the trouble arose. "It can't be done," said the major. "Look at this pyramid, for example; there are sixteen balls at the base, then nine, then four, then one at the top, making thirty balls in all. But there must be six more balls, or five fewer, to make a square number." "It must be done," insisted the general. "All you have to do is to put the right number of balls in your pyramids." "I've got it!" said a lieutenant, the mathematical genius of the regiment. "Lay the balls out singly." "Bosh!" exclaimed the general. "You can't pile one ball into a pyramid!" Is it really possible to obey both orders?

Sources:

"All cannon-balls are to be piled in square pyramids," was the order issued to the regiment. This was done. Then came the further order, "All pyramids are to contain a square number of balls." Whereupon the trouble arose. "It can't be done," said the major. "Look at this pyramid, for example; there are sixteen balls at the base, then nine, then four, then one at the top, making thirty balls in all. But there must be six more balls, or five fewer, to make a square number." "It must be done," insisted the general. "All you have to do is to put the right number of balls in your pyramids." "I've got it!" said a lieutenant, the mathematical genius of the regiment. "Lay the balls out singly." "Bosh!" exclaimed the general. "You can't pile one ball into a pyramid!" Is it really possible to obey both orders?

Sources:

- Amusements in Mathematics, Henry Ernest Dudeney Question 138

-

COUNTING THE RECTANGLES

Can you say correctly just how many squares and other rectangles the chessboard contains? In other words, in how great a number of different ways is it possible to indicate a square or other rectangle enclosed by lines that separate the squares of the board? Sources:- Amusements in Mathematics, Henry Ernest Dudeney Question 347