Combinatorics, Number Tables

Problems in this category involve grids or tables filled with numbers. Tasks might include finding patterns, determining missing entries based on a rule, calculating sums of rows/columns/diagonals, or analyzing properties of specific arrangements like magic squares.

-

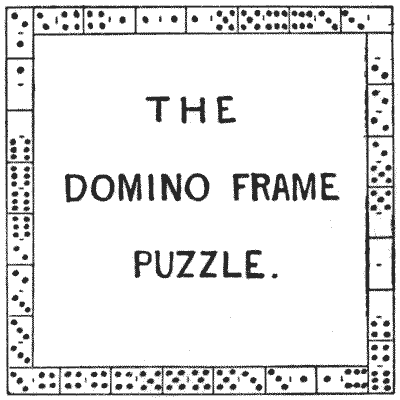

THE DOMINO FRAME PUZZLE

It will be seen in the illustration that the full set of twenty-eight dominoes is arranged in the form of a square frame, with `6` against `6, 2` against `2`, blank against blank, and so on, as in the game. It will be found that the pips in the top row and left-hand column both add up `44`. The pips in the other two sides sum to `59` and `32` respectively. The puzzle is to rearrange the dominoes in the same form so that all of the four sides shall sum to `44`. Remember that the dominoes must be correctly placed one against another as in the game.

Sources:

It will be seen in the illustration that the full set of twenty-eight dominoes is arranged in the form of a square frame, with `6` against `6, 2` against `2`, blank against blank, and so on, as in the game. It will be found that the pips in the top row and left-hand column both add up `44`. The pips in the other two sides sum to `59` and `32` respectively. The puzzle is to rearrange the dominoes in the same form so that all of the four sides shall sum to `44`. Remember that the dominoes must be correctly placed one against another as in the game.

Sources:

- Amusements in Mathematics, Henry Ernest Dudeney Question 380

-

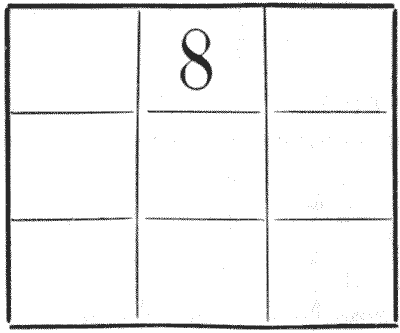

THE TROUBLESOME EIGHT

Nearly everybody knows that a "magic square" is an arrangement of numbers in the form of a square so that every row, every column, and each of the two long diagonals adds up alike. For example, you would find little difficulty in merely placing a different number in each of the nine cells in the illustration so that the rows, columns, and diagonals shall all add up `15`. And at your first attempt you will probably find that you have an `8` in one of the corners. The puzzle is to construct the magic square, under the same conditions, with the `8` in the position shown. Sources:Topics:Combinatorics -> Number Tables

Sources:Topics:Combinatorics -> Number Tables- Amusements in Mathematics, Henry Ernest Dudeney Question 399

-

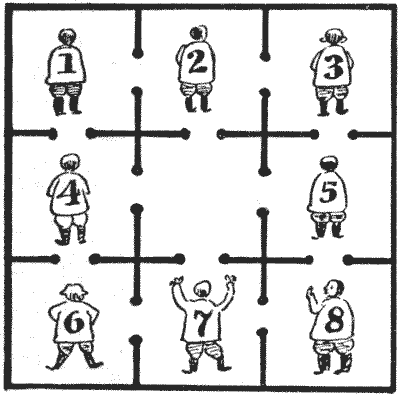

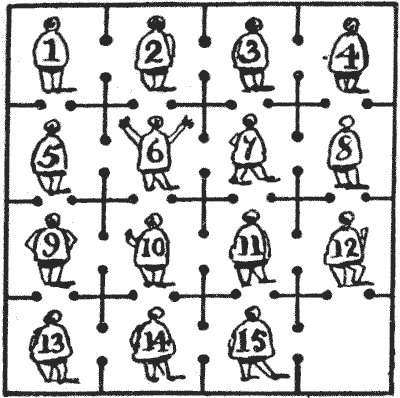

EIGHT JOLLY GAOL BIRDS

The illustration shows the plan of a prison of nine cells all communicating with one another by doorways. The eight prisoners have their numbers on their backs, and any one of them is allowed to exercise himself in whichever cell may happen to be vacant, subject to the rule that at no time shall two prisoners be in the same cell. The merry monarch in whose dominions the prison was situated offered them special comforts one Christmas Eve if, without breaking that rule, they could so place themselves that their numbers should form a magic square.

Now, prisoner No. `7` happened to know a good deal about magic squares, so he worked out a scheme and naturally selected the method that was most expeditious—that is, one involving the fewest possible moves from cell to cell. But one man was a surly, obstinate fellow (quite unfit for the society of his jovial companions), and he refused to move out of his cell or take any part in the proceedings. But No. `7` was quite equal to the emergency, and found that he could still do what was required in the fewest possible moves without troubling the brute to leave his cell. The puzzle is to show how he did it and, incidentally, to discover which prisoner was so stupidly obstinate. Can you find the fellow?

Sources:- Amusements in Mathematics, Henry Ernest Dudeney Question 401

-

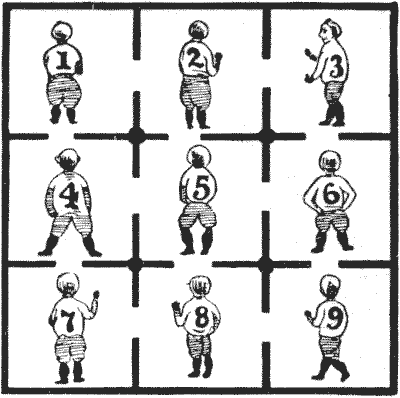

NINE JOLLY GAOL BIRDS

Shortly after the episode recorded in the last puzzle occurred, a ninth prisoner was placed in the vacant cell, and the merry monarch then offered them all complete liberty on the following strange conditions. They were required so to rearrange themselves in the cells that their numbers formed a magic square without their movements causing any two of them ever to be in the same cell together, except that at the start one man was allowed to be placed on the shoulders of another man, and thus add their numbers together, and move as one man. For example, No. `8` might be placed on the shoulders of No. `2`, and then they would move about together as `10`. The reader should seek first to solve the puzzle in the fewest possible moves, and then see that the man who is burdened has the least possible amount of work to do.

Sources:Topics:Combinatorics -> Number Tables

Shortly after the episode recorded in the last puzzle occurred, a ninth prisoner was placed in the vacant cell, and the merry monarch then offered them all complete liberty on the following strange conditions. They were required so to rearrange themselves in the cells that their numbers formed a magic square without their movements causing any two of them ever to be in the same cell together, except that at the start one man was allowed to be placed on the shoulders of another man, and thus add their numbers together, and move as one man. For example, No. `8` might be placed on the shoulders of No. `2`, and then they would move about together as `10`. The reader should seek first to solve the puzzle in the fewest possible moves, and then see that the man who is burdened has the least possible amount of work to do.

Sources:Topics:Combinatorics -> Number Tables- Amusements in Mathematics, Henry Ernest Dudeney Question 402

-

THE SPANISH DUNGEON

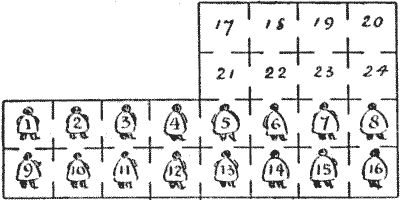

Not fifty miles from Cadiz stood in the middle ages a castle, all traces of which have for centuries disappeared. Among other interesting features, this castle contained a particularly unpleasant dungeon divided into sixteen cells, all communicating with one another, as shown in the illustration.

Now, the governor was a merry wight, and very fond of puzzles withal. One day he went to the dungeon and said to the prisoners, "By my halidame!" (or its equivalent in Spanish) "you shall all be set free if you can solve this puzzle. You must so arrange yourselves in the sixteen cells that the numbers on your backs shall form a magic square in which every column, every row, and each of the two diagonals shall add up the same. Only remember this: that in no case may two of you ever be together in the same cell."

One of the prisoners, after working at the problem for two or three days, with a piece of chalk, undertook to obtain the liberty of himself and his fellow-prisoners if they would follow his directions and move through the doorway from cell to cell in the order in which he should call out their numbers.

He succeeded in his attempt, and, what is more remarkable, it would seem from the account of his method recorded in the ancient manuscript lying before me, that he did so in the fewest possible moves. The reader is asked to show what these moves were.

Sources:Topics:Logic -> Reasoning / Logic Combinatorics -> Case Analysis / Checking Cases -> Processes / Procedures Combinatorics -> Number Tables Algebra -> Word Problems -> Solving Word Problems "From the End" / Working Backwards Puzzles and Rebuses -> Reconstruct the Exercise / Cryptarithmetic- Amusements in Mathematics, Henry Ernest Dudeney Question 403

-

THE SIBERIAN DUNGEONS

The above is a trustworthy plan of a certain Russian prison in Siberia. All the cells are numbered, and the prisoners are numbered the same as the cells they occupy. The prison diet is so fattening that these political prisoners are in perpetual fear lest, should their pardon arrive, they might not be able to squeeze themselves through the narrow doorways and get out. And of course it would be an unreasonable thing to ask any government to pull down the walls of a prison just to liberate the prisoners, however innocent they might be. Therefore these men take all the healthy exercise they can in order to retard their increasing obesity, and one of their recreations will serve to furnish us with the following puzzle.

Show, in the fewest possible moves, how the sixteen men may form themselves into a magic square, so that the numbers on their backs shall add up the same in each of the four columns, four rows, and two diagonals without two prisoners having been at any time in the same cell together. I had better say, for the information of those who have not yet been made acquainted with these places, that it is a peculiarity of prisons that you are not allowed to go outside their walls. Any prisoner may go any distance that is possible in a single move.

Sources:Topics:Number Theory Combinatorics -> Case Analysis / Checking Cases -> Processes / Procedures Combinatorics -> Number Tables- Amusements in Mathematics, Henry Ernest Dudeney Question 404

-

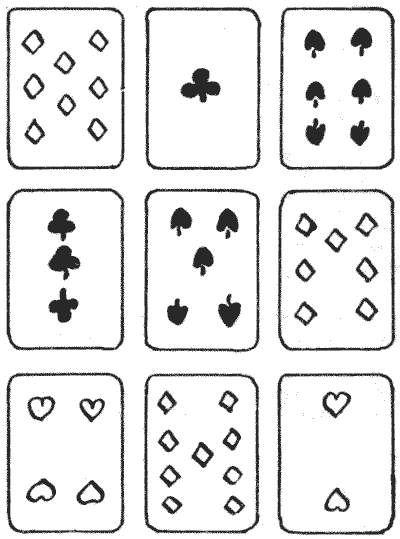

CARD MAGIC SQUARES

Take an ordinary pack of cards and throw out the twelve court cards. Now, with nine of the remainder (different suits are of no consequence) form the above magic square. It will be seen that the pips add up fifteen in every row in every column, and in each of the two long diagonals. The puzzle is with the remaining cards (without disturbing this arrangement) to form three more such magic squares, so that each of the four shall add up to a different sum. There will, of course, be four cards in the reduced pack that will not be used. These four may be any that you choose. It is not a difficult puzzle, but requires just a little thought.

Sources:Topics:Combinatorics -> Number Tables

Take an ordinary pack of cards and throw out the twelve court cards. Now, with nine of the remainder (different suits are of no consequence) form the above magic square. It will be seen that the pips add up fifteen in every row in every column, and in each of the two long diagonals. The puzzle is with the remaining cards (without disturbing this arrangement) to form three more such magic squares, so that each of the four shall add up to a different sum. There will, of course, be four cards in the reduced pack that will not be used. These four may be any that you choose. It is not a difficult puzzle, but requires just a little thought.

Sources:Topics:Combinatorics -> Number Tables- Amusements in Mathematics, Henry Ernest Dudeney Question 405

-

TWO NEW MAGIC SQUARES

Construct a subtracting magic square with the first sixteen whole numbers that shall be "associated" by subtraction. The constant is, of course, obtained by subtracting the first number from the second in line, the result from the third, and the result again from the fourth. Also construct a dividing magic square of the same order that shall be "associated" by division. The constant is obtained by dividing the second number in a line by the first, the third by the quotient, and the fourth by the next quotient.Sources:Topics:Combinatorics -> Number Tables- Amusements in Mathematics, Henry Ernest Dudeney Question 407

-

MAGIC SQUARES OF TWO DEGREES

While reading a French mathematical work I happened to come across, the following statement: "A very remarkable magic square of `8`, in two degrees, has been constructed by M. Pfeffermann. In other words, he has managed to dispose the sixty-four first numbers on the squares of a chessboard in such a way that the sum of the numbers in every line, every column, and in each of the two diagonals, shall be the same; and more, that if one substitutes for all the numbers their squares, the square still remains magic." I at once set to work to solve this problem, and, although it proved a very hard nut, one was rewarded by the discovery of some curious and beautiful laws that govern it. The reader may like to try his hand at the puzzle.

Sources:- Amusements in Mathematics, Henry Ernest Dudeney Question 408

-

THE MAGIC KNIGHT'S TOUR

Here is a problem that has never yet been solved, nor has its impossibility been demonstrated. Play the knight once to every square of the chessboard in a complete tour, numbering the squares in the order visited, so that when completed the square shall be "magic," adding up to `260` in every column, every row, and each of the two long diagonals. I shall give the best answer that I have been able to obtain, in which there is a slight error in the diagonals alone. Can a perfect solution be found? I am convinced that it cannot, but it is only a "pious opinion."

Sources:Topics:Logic Combinatorics -> Number Tables Combinatorics -> Combinatorial Geometry -> Grid Paper Geometry / Lattice Geometry- Amusements in Mathematics, Henry Ernest Dudeney Question 412