Combinatorics, Graph Theory

Graph Theory studies graphs, which are structures made of vertices (nodes) and edges connecting them. It's used to model relationships. Questions cover topics like paths, cycles, connectivity, graph coloring, trees, and analyzing properties of various types of graphs.

-

Question

In a magical land, there are `2017` cities, and each city is connected by direct roads to at least `1008` other cities. Prove that from any city in the magical land, it is possible to reach any other city (not necessarily by a direct route).

-

Question

Shlomi has a chessboard and a cube whose face size is the same as the size of a square on the board. Shlomi wants to paint the faces of the cube black and white, and then roll the cube across the board so that each time the face touching the board is the same color as the square it touches. The cube is supposed to pass through each square on the board exactly once. Can Shlomi do this? Justify or provide an example.

-

Question

In a certain country, there are more than 101 cities. The capital is connected by flight routes to 100 cities, and every city other than the capital is connected by flight routes to exactly 10 cities. It is given that from any city, it is possible to reach any other city (possibly not by a direct route). Prove that it is possible to close half of the flight routes leading to the capital such that the possibility of reaching any city from any other city is preserved.

Sources: -

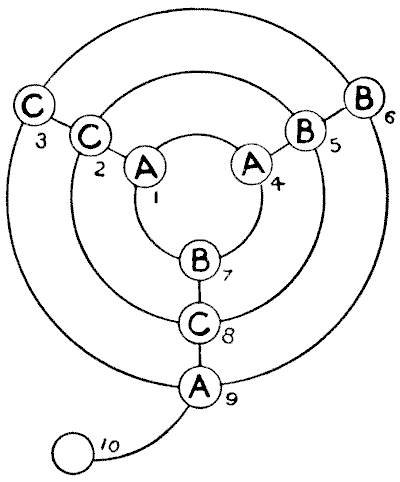

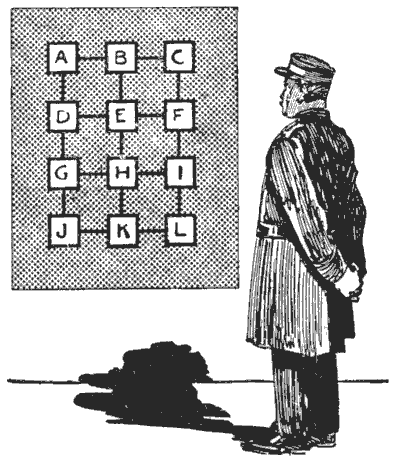

A RAILWAY PUZZLE

Make a diagram, on a large sheet of paper, like the illustration, and have three counters marked A, three marked B, and three marked C. It will be seen that at the intersection of lines there are nine stopping-places, and a tenth stopping-place is attached to the outer circle like the tail of a Q. Place the three counters or engines marked A, the three marked B, and the three marked C at the places indicated. The puzzle is to move the engines, one at a time, along the lines, from stopping-place to stopping-place, until you succeed in getting an A, a B, and a C on each circle, and also A, B, and C on each straight line. You are required to do this in as few moves as possible. How many moves do you need?

Sources:Topics:Combinatorics -> Graph Theory

Make a diagram, on a large sheet of paper, like the illustration, and have three counters marked A, three marked B, and three marked C. It will be seen that at the intersection of lines there are nine stopping-places, and a tenth stopping-place is attached to the outer circle like the tail of a Q. Place the three counters or engines marked A, the three marked B, and the three marked C at the places indicated. The puzzle is to move the engines, one at a time, along the lines, from stopping-place to stopping-place, until you succeed in getting an A, a B, and a C on each circle, and also A, B, and C on each straight line. You are required to do this in as few moves as possible. How many moves do you need?

Sources:Topics:Combinatorics -> Graph Theory- Amusements in Mathematics, Henry Ernest Dudeney Question 222

-

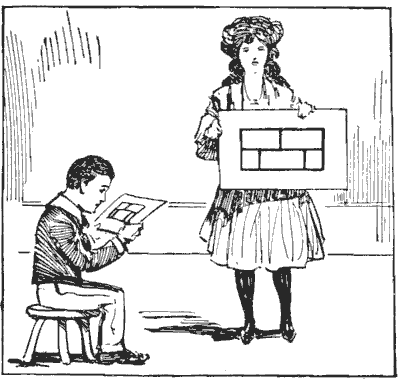

A JUVENILE PUZZLE

For years I have been perpetually consulted by my juvenile friends about this little puzzle. Most children seem to know it, and yet, curiously enough, they are invariably unacquainted with the answer. The question they always ask is, "Do, please, tell me whether it is really possible." I believe Houdin the conjurer used to be very fond of giving it to his child friends, but I cannot say whether he invented the little puzzle or not. No doubt a large number of my readers will be glad to have the mystery of the solution cleared up, so I make no apology for introducing this old "teaser."

The puzzle is to draw with three strokes of the pencil the diagram that the little girl is exhibiting in the illustration. Of course, you must not remove your pencil from the paper during a stroke or go over the same line a second time. You will find that you can get in a good deal of the figure with one continuous stroke, but it will always appear as if four strokes are necessary.

Another form of the puzzle is to draw the diagram on a slate and then rub it out in three rubs.

Sources:Topics:Combinatorics -> Graph Theory- Amusements in Mathematics, Henry Ernest Dudeney Question 239

-

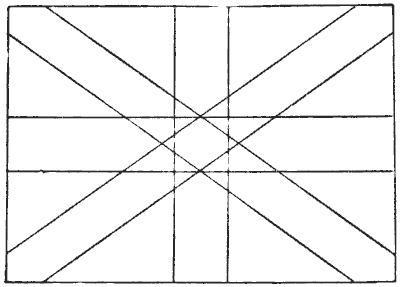

THE UNION JACK

The illustration is a rough sketch somewhat resembling the British flag, the Union Jack. It is not possible to draw the whole of it without lifting the pencil from the paper or going over the same line twice. The puzzle is to find out just how much of the drawing it is possible to make without lifting your pencil or going twice over the same line. Take your pencil and see what is the best you can do.

Sources:Topics:Combinatorics -> Graph Theory

The illustration is a rough sketch somewhat resembling the British flag, the Union Jack. It is not possible to draw the whole of it without lifting the pencil from the paper or going over the same line twice. The puzzle is to find out just how much of the drawing it is possible to make without lifting your pencil or going twice over the same line. Take your pencil and see what is the best you can do.

Sources:Topics:Combinatorics -> Graph Theory- Amusements in Mathematics, Henry Ernest Dudeney Question 240

-

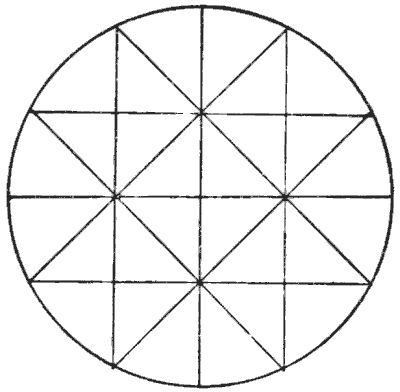

THE DISSECTED CIRCLE

How many continuous strokes, without lifting your pencil from the paper, do you require to draw the design shown in our illustration? Directly you change the direction of your pencil it begins a new stroke. You may go over the same line more than once if you like. It requires just a little care, or you may find yourself beaten by one stroke. Sources:Topics:Combinatorics -> Graph Theory

Sources:Topics:Combinatorics -> Graph Theory- Amusements in Mathematics, Henry Ernest Dudeney Question 241

-

THE TUBE INSPECTOR'S PUZZLE

The man in our illustration is in a little dilemma. He has just been appointed inspector of a certain system of tube railways, and it is his duty to inspect regularly, within a stated period, all the company's seventeen lines connecting twelve stations, as shown on the big poster plan that he is contemplating. Now he wants to arrange his route so that it shall take him over all the lines with as little travelling as possible. He may begin where he likes and end where he likes. What is his shortest route?

Could anything be simpler? But the reader will soon find that, however he decides to proceed, the inspector must go over some of the lines more than once. In other words, if we say that the stations are a mile apart, he will have to travel more than seventeen miles to inspect every line. There is the little difficulty. How far is he compelled to travel, and which route do you recommend?

Sources:Topics:Combinatorics -> Graph Theory

Sources:Topics:Combinatorics -> Graph Theory- Amusements in Mathematics, Henry Ernest Dudeney Question 242

-

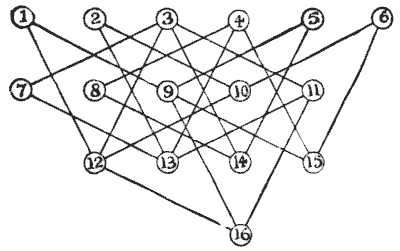

VISITING THE TOWNS

A traveller, starting from town No. `1`, wishes to visit every one of the towns once, and once only, going only by roads indicated by straight lines. How many different routes are there from which he can select? Of course, he must end his journey at No. `1`, from which he started, and must take no notice of cross roads, but go straight from town to town. This is an absurdly easy puzzle, if you go the right way to work.

Sources:Topics:Combinatorics -> Graph Theory

A traveller, starting from town No. `1`, wishes to visit every one of the towns once, and once only, going only by roads indicated by straight lines. How many different routes are there from which he can select? Of course, he must end his journey at No. `1`, from which he started, and must take no notice of cross roads, but go straight from town to town. This is an absurdly easy puzzle, if you go the right way to work.

Sources:Topics:Combinatorics -> Graph Theory- Amusements in Mathematics, Henry Ernest Dudeney Question 243

-

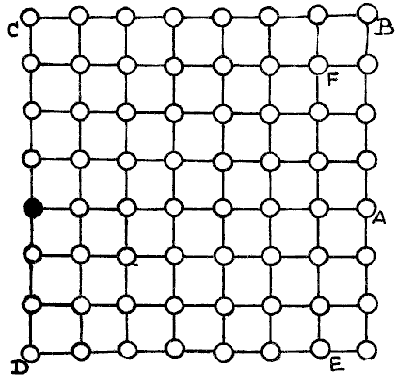

THE FIFTEEN TURNINGS

Here is another queer travelling puzzle, the solution of which calls for ingenuity. In this case the traveller starts from the black town and wishes to go as far as possible while making only fifteen turnings and never going along the same road twice. The towns are supposed to be a mile apart. Supposing, for example, that he went straight to A, then straight to B, then to C, D, E, and F, you will then find that he has travelled thirty-seven miles in five turnings. Now, how far can he go in fifteen turnings? Sources:Topics:Combinatorics -> Graph Theory

Sources:Topics:Combinatorics -> Graph Theory- Amusements in Mathematics, Henry Ernest Dudeney Question 244