Combinatorics, Graph Theory

Graph Theory studies graphs, which are structures made of vertices (nodes) and edges connecting them. It's used to model relationships. Questions cover topics like paths, cycles, connectivity, graph coloring, trees, and analyzing properties of various types of graphs.

-

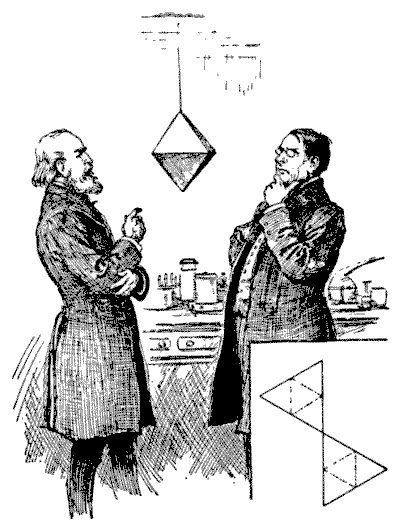

THE FLY ON THE OCTAHEDRON

"Look here," said the professor to his colleague, "I have been watching that fly on the octahedron, and it confines its walks entirely to the edges. What can be its reason for avoiding the sides?"

"Perhaps it is trying to solve some route problem," suggested the other. "Supposing it to start from the top point, how many different routes are there by which it may walk over all the edges, without ever going twice along the same edge in any route?"

The problem was a harder one than they expected, and after working at it during leisure moments for several days their results did not agree—in fact, they were both wrong. If the reader is surprised at their failure, let him attempt the little puzzle himself. I will just explain that the octahedron is one of the five regular, or Platonic, bodies, and is contained under eight equal and equilateral triangles. If you cut out the two pieces of cardboard of the shape shown in the margin of the illustration, cut half through along the dotted lines and then bend them and put them together, you will have a perfect octahedron. In any route over all the edges it will be found that the fly must end at the point of departure at the top.

Sources:Topics:Combinatorics -> Combinatorial Geometry Combinatorics -> Graph Theory Geometry -> Solid Geometry / Geometry in Space -> Polyhedra -> Regular Polyhedra- Amusements in Mathematics, Henry Ernest Dudeney Question 245

-

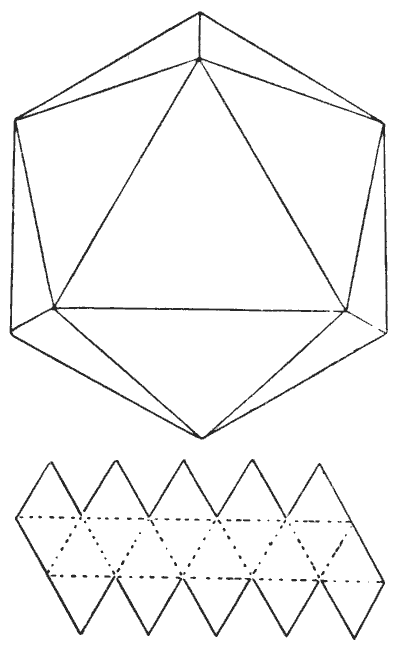

THE ICOSAHEDRON PUZZLE

The icosahedron is another of the five regular, or Platonic, bodies having all their sides, angles, and planes similar and equal. It is bounded by twenty similar equilateral triangles. If you cut out a piece of cardboard of the form shown in the smaller diagram, and cut half through along the dotted lines, it will fold up and form a perfect icosahedron.

Now, a Platonic body does not mean a heavenly body; but it will suit the purpose of our puzzle if we suppose there to be a habitable planet of this shape. We will also suppose that, owing to a superfluity of water, the only dry land is along the edges, and that the inhabitants have no knowledge of navigation. If every one of those edges is `10,000` miles long and a solitary traveller is placed at the North Pole (the highest point shown), how far will he have to travel before he will have visited every habitable part of the planet—that is, have traversed every one of the edges?

Sources:Topics:Combinatorics -> Combinatorial Geometry Combinatorics -> Graph Theory Geometry -> Solid Geometry / Geometry in Space -> Polyhedra -> Regular Polyhedra

Sources:Topics:Combinatorics -> Combinatorial Geometry Combinatorics -> Graph Theory Geometry -> Solid Geometry / Geometry in Space -> Polyhedra -> Regular Polyhedra- Amusements in Mathematics, Henry Ernest Dudeney Question 246

-

INSPECTING A MINE

The diagram is supposed to represent the passages or galleries in a mine. We will assume that every passage, A to B, B to C, C to H, H to I, and so on, is one furlong in length. It will be seen that there are thirty-one of these passages. Now, an official has to inspect all of them, and he descends by the shaft to the point A. How far must he travel, and what route do you recommend? The reader may at first say, "As there are thirty-one passages, each a furlong in length, he will have to travel just thirty-one furlongs." But this is assuming that he need never go along a passage more than once, which is not the case. Take your pencil and try to find the shortest route. You will soon discover that there is room for considerable judgment. In fact, it is a perplexing puzzle. Sources:Topics:Combinatorics -> Graph Theory

Sources:Topics:Combinatorics -> Graph Theory- Amusements in Mathematics, Henry Ernest Dudeney Question 247

-

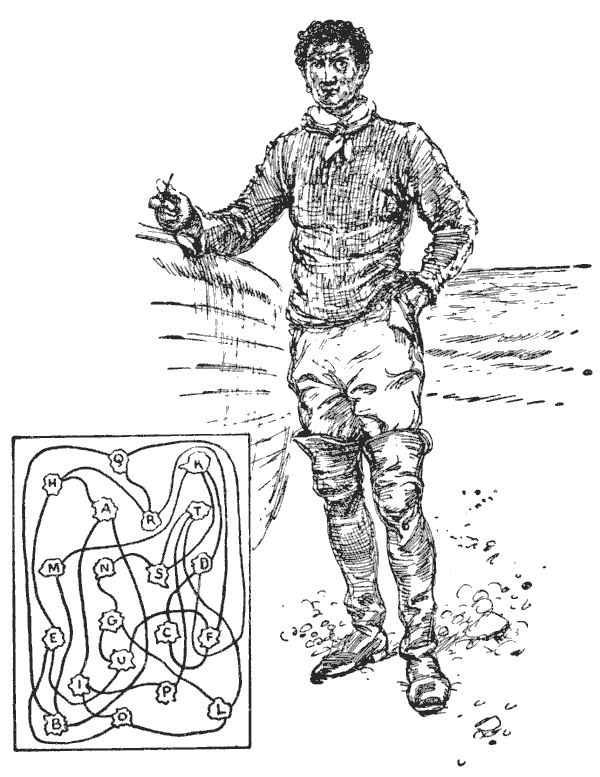

THE SAILOR'S PUZZLE

The sailor depicted in the illustration stated that he had since his boyhood been engaged in trading with a small vessel among some twenty little islands in the Pacific. He supplied the rough chart of which I have given a copy, and explained that the lines from island to island represented the only routes that he ever adopted. He always started from island A at the beginning of the season, and then visited every island once, and once only, finishing up his tour at the starting-point A. But he always put off his visit to C as long as possible, for trade reasons that I need not enter into. The puzzle is to discover his exact route, and this can be done with certainty. Take your pencil and, starting at A, try to trace it out. If you write down the islands in the order in which you visit them—thus, for example, A, I, O, L, G, etc.—you can at once see if you have visited an island twice or omitted any. Of course, the crossings of the lines must be ignored—that is, you must continue your route direct, and you are not allowed to switch off at a crossing and proceed in another direction. There is no trick of this kind in the puzzle. The sailor knew the best route. Can you find it? Sources:Topics:Combinatorics -> Graph Theory

Sources:Topics:Combinatorics -> Graph Theory- Amusements in Mathematics, Henry Ernest Dudeney Question 249

-

THE GRAND TOUR

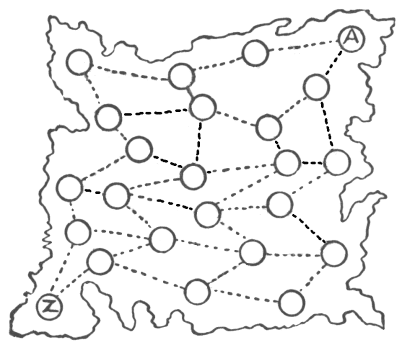

One of the everyday puzzles of life is the working out of routes. If you are taking a holiday on your bicycle, or a motor tour, there always arises the question of how you are to make the best of your time and other resources. You have determined to get as far as some particular place, to include visits to such-and-such a town, to try to see something of special interest elsewhere, and perhaps to try to look up an old friend at a spot that will not take you much out of your way. Then you have to plan your route so as to avoid bad roads, uninteresting country, and, if possible, the necessity of a return by the same way that you went. With a map before you, the interesting puzzle is attacked and solved. I will present a little poser based on these lines.

I give a rough map of a country—it is not necessary to say what particular country—the circles representing towns and the dotted lines the railways connecting them. Now there lived in the town marked A a man who was born there, and during the whole of his life had never once left his native place. From his youth upwards he had been very industrious, sticking incessantly to his trade, and had no desire whatever to roam abroad. However, on attaining his fiftieth birthday he decided to see something of his country, and especially to pay a visit to a very old friend living at the town marked Z. What he proposed was this: that he would start from his home, enter every town once and only once, and finish his journey at Z. As he made up his mind to perform this grand tour by rail only, he found it rather a puzzle to work out his route, but he at length succeeded in doing so. How did he manage it? Do not forget that every town has to be visited once, and not more than once.

Sources:Topics:Combinatorics -> Combinatorial Geometry Combinatorics -> Graph Theory Logic -> Reasoning / Logic Combinatorics -> Case Analysis / Checking Cases -> Processes / Procedures Puzzles and Rebuses

Sources:Topics:Combinatorics -> Combinatorial Geometry Combinatorics -> Graph Theory Logic -> Reasoning / Logic Combinatorics -> Case Analysis / Checking Cases -> Processes / Procedures Puzzles and Rebuses- Amusements in Mathematics, Henry Ernest Dudeney Question 250

-

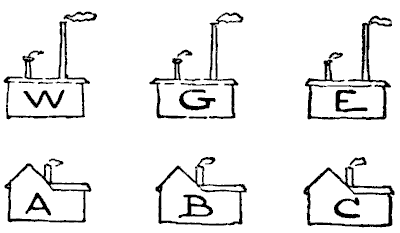

WATER, GAS, AND ELECTRICITY

There are some half-dozen puzzles, as old as the hills, that are perpetually cropping up, and there is hardly a month in the year that does not bring inquiries as to their solution. Occasionally one of these, that one had thought was an extinct volcano, bursts into eruption in a surprising manner. I have received an extraordinary number of letters respecting the ancient puzzle that I have called "Water, Gas, and Electricity." It is much older than electric lighting, or even gas, but the new dress brings it up to date. The puzzle is to lay on water, gas, and electricity, from W, G, and E, to each of the three houses, A, B, and C, without any pipe crossing another. Take your pencil and draw lines showing how this should be done. You will soon find yourself landed in difficulties. Sources:

Sources:

- Amusements in Mathematics, Henry Ernest Dudeney Question 251

-

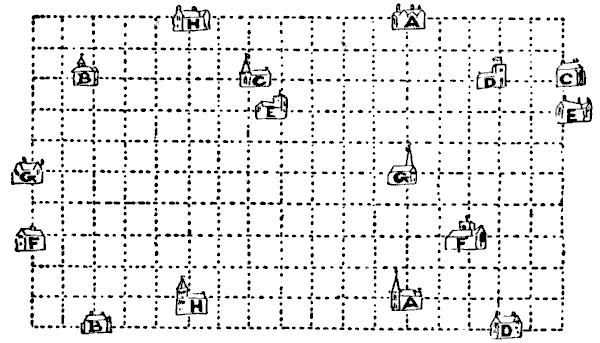

A PUZZLE FOR MOTORISTS

Eight motorists drove to church one morning. Their respective houses and churches, together with the only roads available (the dotted lines), are shown. One went from his house A to his church A, another from his house B to his church B, another from C to C, and so on, but it was afterwards found that no driver ever crossed the track of another car. Take your pencil and try to trace out their various routes.

Sources:Topics:Combinatorics -> Graph Theory

Eight motorists drove to church one morning. Their respective houses and churches, together with the only roads available (the dotted lines), are shown. One went from his house A to his church A, another from his house B to his church B, another from C to C, and so on, but it was afterwards found that no driver ever crossed the track of another car. Take your pencil and try to trace out their various routes.

Sources:Topics:Combinatorics -> Graph Theory- Amusements in Mathematics, Henry Ernest Dudeney Question 252

-

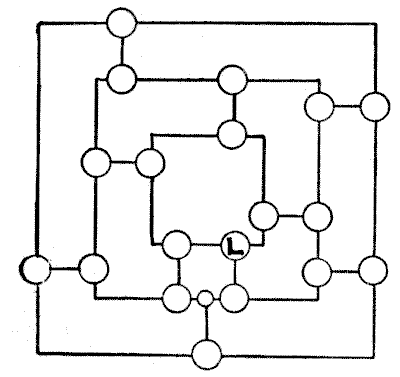

THE MOTOR-CAR TOUR

In the above diagram the circles represent towns and the lines good roads. In just how many different ways can a motorist, starting from London (marked with an L), make a tour of all these towns, visiting every town once, and only once, on a tour, and always coming back to London on the last ride? The exact reverse of any route is not counted as different.

Sources:Topics:Combinatorics -> Graph Theory

In the above diagram the circles represent towns and the lines good roads. In just how many different ways can a motorist, starting from London (marked with an L), make a tour of all these towns, visiting every town once, and only once, on a tour, and always coming back to London on the last ride? The exact reverse of any route is not counted as different.

Sources:Topics:Combinatorics -> Graph Theory- Amusements in Mathematics, Henry Ernest Dudeney Question 254

-

THE MONK AND THE BRIDGES

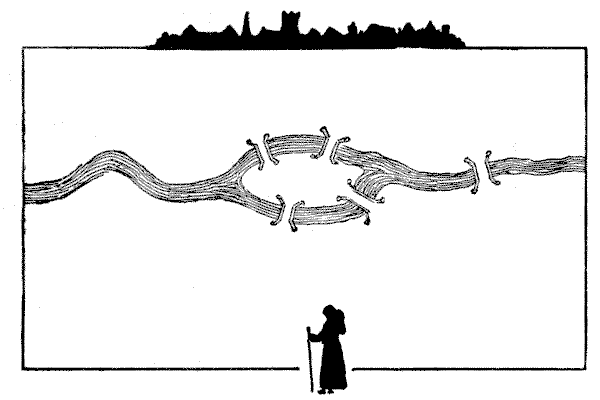

In this case I give a rough plan of a river with an island and five bridges. On one side of the river is a monastery, and on the other side is seen a monk in the foreground. Now, the monk has decided that he will cross every bridge once, and only once, on his return to the monastery. This is, of course, quite easy to do, but on the way he thought to himself, "I wonder how many different routes there are from which I might have selected." Could you have told him? That is the puzzle. Take your pencil and trace out a route that will take you once over all the five bridges. Then trace out a second route, then a third, and see if you can count all the variations. You will find that the difficulty is twofold: you have to avoid dropping routes on the one hand and counting the same routes more than once on the other.

Sources:Topics:Combinatorics -> Graph Theory

Sources:Topics:Combinatorics -> Graph Theory- Amusements in Mathematics, Henry Ernest Dudeney Question 261

-

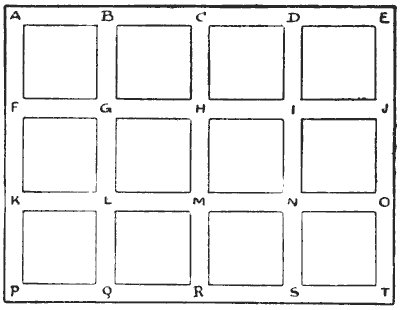

THE ROOK'S TOUR

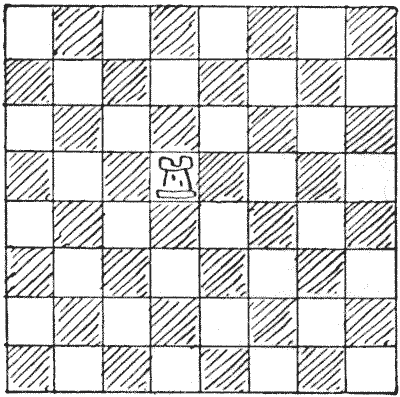

The puzzle is to move the single rook over the whole board, so that it shall visit every square of the board once, and only once, and end its tour on the square from which it starts. You have to do this in as few moves as possible, and unless you are very careful you will take just one move too many. Of course, a square is regarded equally as "visited" whether you merely pass over it or make it a stopping-place, and we will not quibble over the point whether the original square is actually visited twice. We will assume that it is not.

Sources:Topics:Combinatorics -> Graph Theory

The puzzle is to move the single rook over the whole board, so that it shall visit every square of the board once, and only once, and end its tour on the square from which it starts. You have to do this in as few moves as possible, and unless you are very careful you will take just one move too many. Of course, a square is regarded equally as "visited" whether you merely pass over it or make it a stopping-place, and we will not quibble over the point whether the original square is actually visited twice. We will assume that it is not.

Sources:Topics:Combinatorics -> Graph Theory- Amusements in Mathematics, Henry Ernest Dudeney Question 320