Combinatorics, Game Theory

Game Theory is the study of strategic decision-making where multiple players' choices interact. Questions involve analyzing games (like Nim, chess variants, or strategic puzzles) to find optimal strategies, determine winning/losing positions, or understand concepts like equilibrium.

-

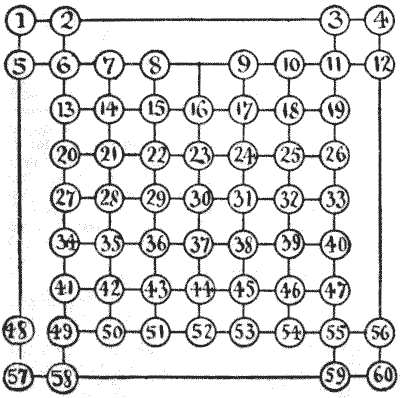

PUSS IN THE CORNER

This variation of the last puzzle is also played by two persons. One puts a counter on No. `6`, and the other puts one on No. `55`, and they play alternately by removing the counter to any other number in a line. If your opponent moves at any time on to one of the lines you occupy, or even crosses one of your lines, you immediately capture him and win. We will take an illustrative game.

A moves from `55` to `52`; B moves from `6` to `13`; A advances to `23`; B goes to `15`; A retreats to `26`; B retreats to `13`; A advances to `21`; B retreats to `2`; A advances to `7`; B goes to `3`; A moves to `6`; B must now go to `4`; A establishes himself at `11`, and B must be captured next move because he is compelled to cross a line on which A stands. Play this over and you will understand the game directly. Now, the puzzle part of the game is this: Which player should win, and how many moves are necessary?

Sources:Topics:Combinatorics -> Game Theory- Amusements in Mathematics, Henry Ernest Dudeney Question 394

-

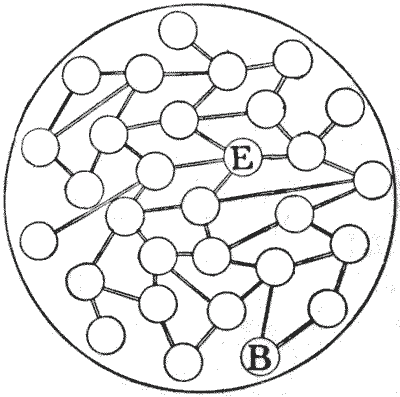

A WAR PUZZLE GAME

Here is another puzzle game. One player, representing the British general, places a counter at B, and the other player, representing the enemy, places his counter at E. The Britisher makes the first advance along one of the roads to the next town, then the enemy moves to one of his nearest towns, and so on in turns, until the British general gets into the same town as the enemy and captures him. Although each must always move along a road to the next town only, and the second player may do his utmost to avoid capture, the British general (as we should suppose, from the analogy of real life) must infallibly win. But how? That is the question.

Sources:Topics:Combinatorics -> Game Theory

Here is another puzzle game. One player, representing the British general, places a counter at B, and the other player, representing the enemy, places his counter at E. The Britisher makes the first advance along one of the roads to the next town, then the enemy moves to one of his nearest towns, and so on in turns, until the British general gets into the same town as the enemy and captures him. Although each must always move along a road to the next town only, and the second player may do his utmost to avoid capture, the British general (as we should suppose, from the analogy of real life) must infallibly win. But how? That is the question.

Sources:Topics:Combinatorics -> Game Theory- Amusements in Mathematics, Henry Ernest Dudeney Question 395

-

A MATCH MYSTERY

Here is a little game that is childishly simple in its conditions. But it is well worth investigation.

Mr. Stubbs pulled a small table between himself and his friend, Mr. Wilson, and took a box of matches, from which he counted out thirty.

"Here are thirty matches," he said. "I divide them into three unequal heaps. Let me see. We have `14, 11`, and `5`, as it happens. Now, the two players draw alternately any number from any one heap, and he who draws the last match loses the game. That's all! I will play with you, Wilson. I have formed the heaps, so you have the first draw."

"As I can draw any number," Mr. Wilson said, "suppose I exhibit my usual moderation and take all the `14` heap."

"That is the worst you could do, for it loses right away. I take `6` from the `11`, leaving two equal heaps of `5`, and to leave two equal heaps is a certain win (with the single exception of `1, 1`), because whatever you do in one heap I can repeat in the other. If you leave `4` in one heap, I leave `4` in the other. If you then leave `2` in one heap, I leave `2` in the other. If you leave only `1` in one heap, then I take all the other heap. If you take all one heap, I take all but one in the other. No, you must never leave two heaps, unless they are equal heaps and more than `1, 1`. Let's begin again."

"Very well, then," said Mr. Wilson. "I will take `6` from the `14`, and leave you `8, 11, 5`."

Mr. Stubbs then left `8, 11, 3`; Mr. Wilson, `8, 5, 3`; Mr. Stubbs, `6, 5, 3`; Mr. Wilson,`4, 5, 3`; Mr. Stubbs, `4, 5, 1`; Mr. Wilson, `4, 3, 1`; Mr. Stubbs, `2, 3, 1`; Mr. Wilson, `2, 1, 1`; which Mr. Stubbs reduced to `1, 1, 1`.

"It is now quite clear that I must win," said Mr. Stubbs, because you must take `1`, and then I take `1`, leaving you the last match. You never had a chance. There are just thirteen different ways in which the matches may be grouped at the start for a certain win. In fact, the groups selected, `14, 11, 5`, are a certain win, because for whatever your opponent may play there is another winning group you can secure, and so on and on down to the last match."

Sources:Topics:Combinatorics -> Game Theory- Amusements in Mathematics, Henry Ernest Dudeney Question 396

-

THE CIGAR PUZZLE

I once propounded the following puzzle in a London club, and for a considerable period it absorbed the attention of the members. They could make nothing of it, and considered it quite impossible of solution. And yet, as I shall show, the answer is remarkably simple.

Two men are seated at a square-topped table. One places an ordinary cigar (flat at one end, pointed at the other) on the table, then the other does the same, and so on alternately, a condition being that no cigar shall touch another. Which player should succeed in placing the last cigar, assuming that they each will play in the best possible manner? The size of the table top and the size of the cigar are not given, but in order to exclude the ridiculous answer that the table might be so diminutive as only to take one cigar, we will say that the table must not be less than `2` feet square and the cigar not more than `4`½ inches long. With those restrictions you may take any dimensions you like. Of course we assume that all the cigars are exactly alike in every respect. Should the first player, or the second player, win?

Sources:Topics:Combinatorics -> Game Theory Logic -> Reasoning / Logic Geometry -> Plane Geometry -> Symmetry- Amusements in Mathematics, Henry Ernest Dudeney Question 398