Combinatorics, Game Theory

Game Theory is the study of strategic decision-making where multiple players' choices interact. Questions involve analyzing games (like Nim, chess variants, or strategic puzzles) to find optimal strategies, determine winning/losing positions, or understand concepts like equilibrium.

-

Wolf and sheep

The game takes place on an infinite plane. One player moves the wolf, and the other – 50 sheep. After a move by the wolf, one of the sheep makes a move, then the wolf again, and so on. In one move, the wolf or sheep moves no more than one meter in any direction. Can the wolf always catch at least one sheep, regardless of the initial configuration?

Sources:Topics:Combinatorics -> Combinatorial Geometry Combinatorics -> Invariants Combinatorics -> Game Theory Proof and Example -> Constructing an Example / Counterexample- Tournament of Towns, 1980-1981, Spring, Main Version, Grades 9-10 Question 5 Points 16

-

Playing with Chocolate

Yossi and Danny are playing the following game. They have a chocolate bar of size `5xx7` squares, which is placed on a table. Each player, in turn, breaks one of the pieces of chocolate on the table along a straight line and returns the resulting pieces to the table. That is, in the first turn, the original chocolate bar is broken, and in the following turns, one piece is chosen from the pieces created up to that point and broken. It is only possible to break along the lines of the squares, and each break is from edge to edge. The player who cannot make a move loses. The winner eats all the chocolate.

Which of the two can guarantee a victory for themselves, if Yossi makes the first move?

-

Game with Piles of Stones

Two players are playing the following game. On the table are three piles of stones. The first pile has `10` stones, the second – `15`, and the third – `20`. Each player, in their turn, chooses one of the piles currently on the table and divides it into two smaller piles. The player who cannot make a move loses.

Which of the two players has a winning strategy, and what is it?

Sources: -

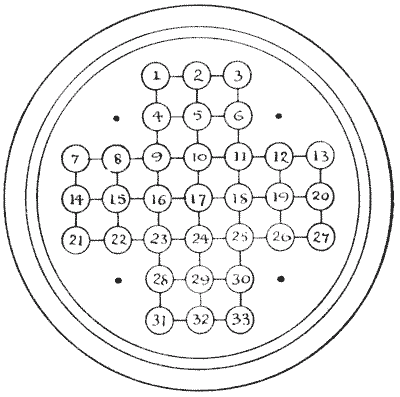

CENTRAL SOLITAIRE

This ancient puzzle was a great favourite with our grandmothers, and most of us, I imagine, have on occasions come across a "Solitaire" board—a round polished board with holes cut in it in a geometrical pattern, and a glass marble in every hole. Sometimes I have noticed one on a side table in a suburban front parlour, or found one on a shelf in a country cottage, or had one brought under my notice at a wayside inn. Sometimes they are of the form shown above, but it is equally common for the board to have four more holes, at the points indicated by dots. I select the simpler form.

Though "Solitaire" boards are still sold at the toy shops, it will be sufficient if the reader will make an enlarged copy of the above on a sheet of cardboard or paper, number the "holes," and provide himself with `33` counters, buttons, or beans. Now place a counter in every hole except the central one, No. `17`, and the puzzle is to take off all the counters in a series of jumps, except the last counter, which must be left in that central hole. You are allowed to jump one counter over the next one to a vacant hole beyond, just as in the game of draughts, and the counter jumped over is immediately taken off the board. Only remember every move must be a jump; consequently you will take off a counter at each move, and thirty-one single jumps will of course remove all the thirty-one counters. But compound moves are allowed (as in draughts, again), for so long as one counter continues to jump, the jumps all count as one move.

Here is the beginning of an imaginary solution which will serve to make the manner of moving perfectly plain, and show how the solver should write out his attempts: `5-17`, `12-10`, `26-12`, `24-26` (`13-11`, `11-25`), `9-11` (`26-24`, `24-10`, `10-12`), etc., etc. The jumps contained within brackets count as one move, because they are made with the same counter. Find the fewest possible moves. Of course, no diagonal jumps are permitted; you can only jump in the direction of the lines.

Sources:- Amusements in Mathematics, Henry Ernest Dudeney Question 227

-

AN EPISCOPAL VISITATION

The white squares on the chessboard represent the parishes of a diocese. Place the bishop on any square you like, and so contrive that (using the ordinary bishop's move of chess) he shall visit every one of his parishes in the fewest possible moves. Of course, all the parishes passed through on any move are regarded as "visited." You can visit any squares more than once, but you are not allowed to move twice between the same two adjoining squares. What are the fewest possible moves? The bishop need not end his visitation at the parish from which he first set out.Sources:Topics:Combinatorics -> Graph Theory Combinatorics -> Game Theory Combinatorics -> Colorings -> Chessboard Coloring Puzzles and Rebuses- Amusements in Mathematics, Henry Ernest Dudeney Question 325

-

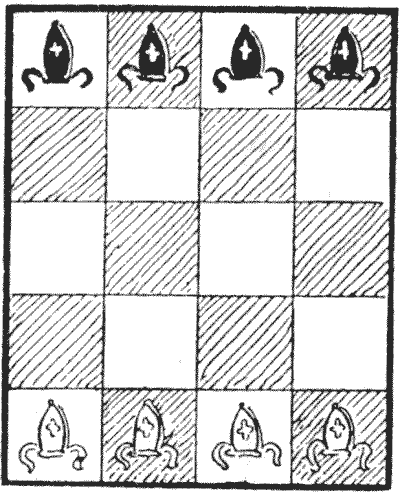

A NEW BISHOP'S PUZZLE

This is quite a fascinating little puzzle. Place eight bishops (four black and four white) on the reduced chessboard, as shown in the illustration. The problem is to make the black bishops change places with the white ones, no bishop ever attacking another of the opposite colour. They must move alternately—first a white, then a black, then a white, and so on. When you have succeeded in doing it at all, try to find the fewest possible moves.

If you leave out the bishops standing on black squares, and only play on the white squares, you will discover my last puzzle turned on its side.

Sources:Topics:Combinatorics -> Combinatorial Geometry Combinatorics -> Graph Theory Combinatorics -> Game Theory Logic -> Reasoning / Logic Puzzles and Rebuses- Amusements in Mathematics, Henry Ernest Dudeney Question 327

-

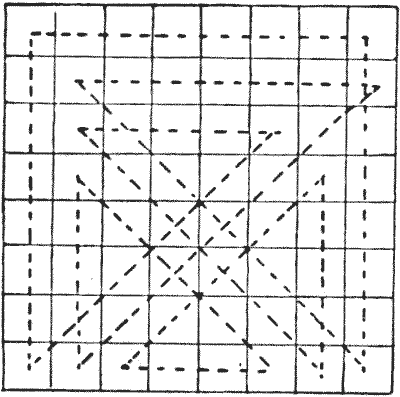

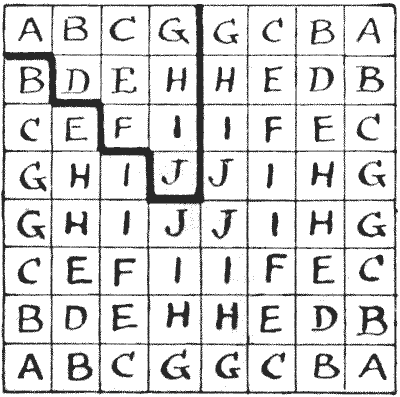

THE QUEEN'S TOUR

The puzzle of making a complete tour of the chessboard with the queen in the fewest possible moves (in which squares may be visited more than once) was first given by the late Sam Loyd in his Chess Strategy. But the solution shown below is the one he gave in American Chess-Nuts in `1868`. I have recorded at least six different solutions in the minimum number of moves—fourteen—but this one is the best of all, for reasons I will explain. If you will look at the lettered square you will understand that there are only ten really differently placed squares on a chessboard—those enclosed by a dark line—all the others are mere reversals or reflections. For example, every A is a corner square, and every J a central square. Consequently, as the solution shown has a turning-point at the enclosed D square, we can obtain a solution starting from and ending at any square marked D—by just turning the board about. Now, this scheme will give you a tour starting from any A, B, C, D, E, F, or H, while no other route that I know can be adapted to more than five different starting-points. There is no Queen's Tour in fourteen moves (remember a tour must be re-entrant) that may start from a G, I, or J. But we can have a non-re-entrant path over the whole board in fourteen moves, starting from any given square. Hence the following puzzle:—

If you will look at the lettered square you will understand that there are only ten really differently placed squares on a chessboard—those enclosed by a dark line—all the others are mere reversals or reflections. For example, every A is a corner square, and every J a central square. Consequently, as the solution shown has a turning-point at the enclosed D square, we can obtain a solution starting from and ending at any square marked D—by just turning the board about. Now, this scheme will give you a tour starting from any A, B, C, D, E, F, or H, while no other route that I know can be adapted to more than five different starting-points. There is no Queen's Tour in fourteen moves (remember a tour must be re-entrant) that may start from a G, I, or J. But we can have a non-re-entrant path over the whole board in fourteen moves, starting from any given square. Hence the following puzzle:—  Start from the J in the enclosed part of the lettered diagram and visit every square of the board in fourteen moves, ending wherever you like.

Sources:Topics:Combinatorics -> Combinatorial Geometry Combinatorics -> Game Theory Combinatorics -> Colorings -> Chessboard Coloring Puzzles and Rebuses

Start from the J in the enclosed part of the lettered diagram and visit every square of the board in fourteen moves, ending wherever you like.

Sources:Topics:Combinatorics -> Combinatorial Geometry Combinatorics -> Game Theory Combinatorics -> Colorings -> Chessboard Coloring Puzzles and Rebuses- Amusements in Mathematics, Henry Ernest Dudeney Question 328

-

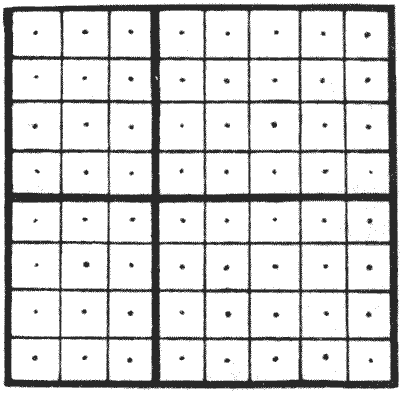

THE BOARD IN COMPARTMENTS

We cannot divide the ordinary chessboard into four equal square compartments, and describe a complete tour, or even path, in each compartment. But we may divide it into four compartments, as in the illustration, two containing each twenty squares, and the other two each twelve squares, and so obtain an interesting puzzle. You are asked to describe a complete re-entrant tour on this board, starting where you like, but visiting every square in each successive compartment before passing into another one, and making the final leap back to the square from which the knight set out. It is not difficult, but will be found very entertaining and not uninstructive.

Whether a re-entrant "tour" or a complete knight's "path" is possible or not on a rectangular board of given dimensions depends not only on its dimensions, but also on its shape. A tour is obviously not possible on a board containing an odd number of cells, such as `5` by `5` or `7` by `7`, for this reason: Every successive leap of the knight must be from a white square to a black and a black to a white alternately. But if there be an odd number of cells or squares there must be one more square of one colour than of the other, therefore the path must begin from a square of the colour that is in excess, and end on a similar colour, and as a knight's move from one colour to a similar colour is impossible the path cannot be re-entrant. But a perfect tour may be made on a rectangular board of any dimensions provided the number of squares be even, and that the number of squares on one side be not less than `6` and on the other not less than `5`. In other words, the smallest rectangular board on which a re-entrant tour is possible is one that is `6` by `5`.

A complete knight's path (not re-entrant) over all the squares of a board is never possible if there be only two squares on one side; nor is it possible on a square board of smaller dimensions than `5` by `5`. So that on a board `4` by `4` we can neither describe a knight's tour nor a complete knight's path; we must leave one square unvisited. Yet on a board `4` by `3` (containing four squares fewer) a complete path may be described in sixteen different ways. It may interest the reader to discover all these. Every path that starts from and ends at different squares is here counted as a different solution, and even reverse routes are called different.

Sources:- Amusements in Mathematics, Henry Ernest Dudeney Question 338

-

THE CUBIC KNIGHT'S TOUR

Some few years ago I happened to read somewhere that Abnit Vandermonde, a clever mathematician, who was born in `1736` and died in `1793`, had devoted a good deal of study to the question of knight's tours. Beyond what may be gathered from a few fragmentary references, I am not aware of the exact nature or results of his investigations, but one thing attracted my attention, and that was the statement that he had proposed the question of a tour of the knight over the six surfaces of a cube, each surface being a chessboard. Whether he obtained a solution or not I do not know, but I have never seen one published. So I at once set to work to master this interesting problem. Perhaps the reader may like to attempt it. Sources:- Amusements in Mathematics, Henry Ernest Dudeney Question 340

-

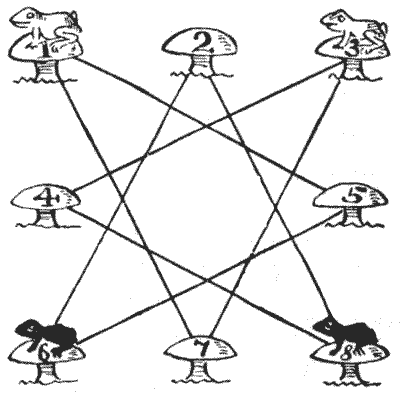

THE FOUR FROGS

In the illustration we have eight toadstools, with white frogs on `1` and `3` and black frogs on `6` and `8`. The puzzle is to move one frog at a time, in any order, along one of the straight lines from toadstool to toadstool, until they have exchanged places, the white frogs being left on `6` and `8` and the black ones on `1` and `3`. If you use four counters on a simple diagram, you will find this quite easy, but it is a little more puzzling to do it in only seven plays, any number of successive moves by one frog counting as one play. Of course, more than one frog cannot be on a toadstool at the same time.

Sources:

In the illustration we have eight toadstools, with white frogs on `1` and `3` and black frogs on `6` and `8`. The puzzle is to move one frog at a time, in any order, along one of the straight lines from toadstool to toadstool, until they have exchanged places, the white frogs being left on `6` and `8` and the black ones on `1` and `3`. If you use four counters on a simple diagram, you will find this quite easy, but it is a little more puzzling to do it in only seven plays, any number of successive moves by one frog counting as one play. Of course, more than one frog cannot be on a toadstool at the same time.

Sources:

- Amusements in Mathematics, Henry Ernest Dudeney Question 341