Combinatorics, Case Analysis / Checking Cases, Processes / Procedures

Case analysis is a problem-solving technique where a problem is divided into several distinct, exhaustive cases. Each case is then analyzed separately to arrive at a solution or proof. Questions suitable for this involve conditions that naturally split the problem into different scenarios.

-

THE CENTURY PUZZLE

Can you write `100` in the form of a mixed number, using all the nine digits once, and only once? The late distinguished French mathematician, Edouard Lucas, found seven different ways of doing it, and expressed his doubts as to there being any other ways. As a matter of fact there are just eleven ways and no more. Here is one of them, `91 5742/638`. Nine of the other ways have similarly two figures in the integral part of the number, but the eleventh expression has only one figure there. Can the reader find this last form?

Sources:Topics:Number Theory -> Modular Arithmetic / Remainder Arithmetic -> Divisibility Rules Logic -> Reasoning / Logic Arithmetic -> Fractions Combinatorics -> Case Analysis / Checking Cases -> Processes / Procedures- Amusements in Mathematics, Henry Ernest Dudeney Question 90

-

THE DIGITAL CENTURY

`1\ 2\ 3\ 4\ 5\ 6\ 7\ 8\ 9 = 100`.

It is required to place arithmetical signs between the nine figures so that they shall equal `100`. Of course, you must not alter the present numerical arrangement of the figures. Can you give a correct solution that employs (`1`) the fewest possible signs, and (`2`) the fewest possible separate strokes or dots of the pen? That is, it is necessary to use as few signs as possible, and those signs should be of the simplest form. The signs of addition and multiplication (+ and ×) will thus count as two strokes, the sign of subtraction (-) as one stroke, the sign of division (÷) as three, and so on.

Sources:Topics:Arithmetic Combinatorics -> Case Analysis / Checking Cases -> Processes / Procedures Puzzles and Rebuses- Amusements in Mathematics, Henry Ernest Dudeney Question 94

-

THE FIVE BRIGANDS

The five Spanish brigands, Alfonso, Benito, Carlos, Diego, and Esteban, were counting their spoils after a raid, when it was found that they had captured altogether exactly `200` doubloons. One of the band pointed out that if Alfonso had twelve times as much, Benito three times as much, Carlos the same amount, Diego half as much, and Esteban one-third as much, they would still have altogether just `200` doubloons. How many doubloons had each?

There are a good many equally correct answers to this question. Here is one of them:

A 6 × 12 = 72 B 12 × 3 = 36 C 17 × 1 = 17 D 120 × ½ = 60 E 45 × 1/3 = 15 200 200 The puzzle is to discover exactly how many different answers there are, it being understood that every man had something and that there is to be no fractional money—only doubloons in every case.

This problem, worded somewhat differently, was propounded by Tartaglia (died `1559`), and he flattered himself that he had found one solution; but a French mathematician of note (M.A. Labosne), in a recent work, says that his readers will be astonished when he assures them that there are `6,639` different correct answers to the question. Is this so? How many answers are there?

Sources:Topics:Number Theory Arithmetic Algebra -> Word Problems Algebra -> Sequences -> Arithmetic Progression / Arithmetic Sequence Combinatorics -> Case Analysis / Checking Cases -> Processes / Procedures Algebra -> Equations -> Diophantine Equations- Amusements in Mathematics, Henry Ernest Dudeney Question 133

-

THE BURMESE PLANTATION

A short time ago I received an interesting communication from the British chaplain at Meiktila, Upper Burma, in which my correspondent informed me that he had found some amusement on board ship on his way out in trying to solve this little poser.

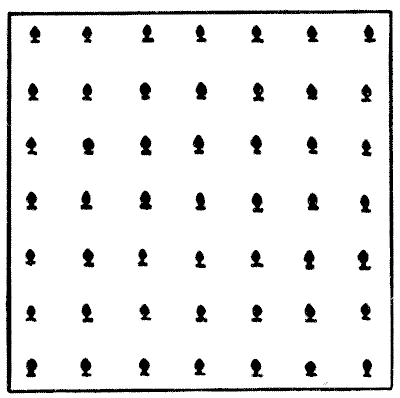

If he has a plantation of forty-nine trees, planted in the form of a square as shown in the accompanying illustration, he wishes to know how he may cut down twenty-seven of the trees so that the twenty-two left standing shall form as many rows as possible with four trees in every row.

Of course there may not be more than four trees in any row.

Sources:Topics:Combinatorics -> Case Analysis / Checking Cases -> Processes / Procedures Combinatorics -> Combinatorial Geometry -> Cut a Shape / Dissection Problems- Amusements in Mathematics, Henry Ernest Dudeney Question 212

-

THE MOTOR-GARAGE PUZZLE

The difficulties of the proprietor of a motor garage are converted into a little pastime of a kind that has a peculiar fascination. All you need is to make a simple plan or diagram on a sheet of paper or cardboard and number eight counters, `1` to `8`. Then a whole family can enter into an amusing competition to find the best possible solution of the difficulty.

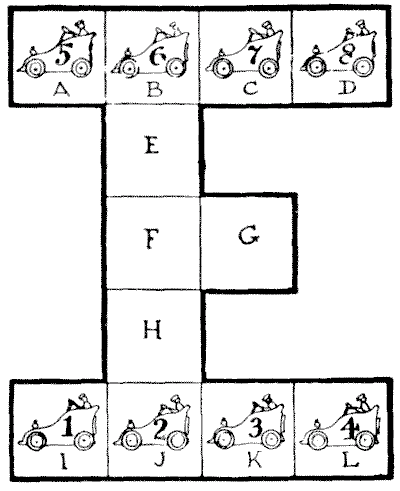

The illustration represents the plan of a motor garage, with accommodation for twelve cars. But the premises are so inconveniently restricted that the proprietor is often caused considerable perplexity. Suppose, for example, that the eight cars numbered `1` to `8` are in the positions shown, how are they to be shifted in the quickest possible way so that `1, 2, 3`, and `4` shall change places with `5, 6, 7`, and `8`—that is, with the numbers still running from left to right, as at present, but the top row exchanged with the bottom row? What are the fewest possible moves?

One car moves at a time, and any distance counts as one move. To prevent misunderstanding, the stopping-places are marked in squares, and only one car can be in a square at the same time.

Sources:Topics:Logic -> Reasoning / Logic Combinatorics -> Case Analysis / Checking Cases -> Processes / Procedures Combinatorics -> Case Analysis / Checking Cases -> Processes / Procedures Puzzles and Rebuses- Amusements in Mathematics, Henry Ernest Dudeney Question 224

-

THE EXCHANGE PUZZLE

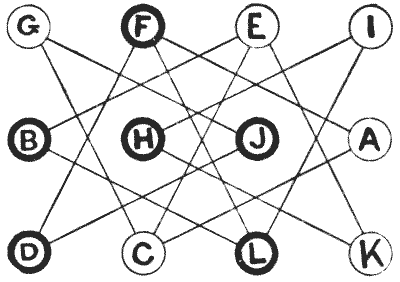

Here is a rather entertaining little puzzle with moving counters. You only need twelve counters—six of one colour, marked A, C, E, G, I, and K, and the other six marked B, D, F, H, J, and L. You first place them on the diagram, as shown in the illustration, and the puzzle is to get them into regular alphabetical order, as follows:—

A B C D E F G H I J K L The moves are made by exchanges of opposite colours standing on the same line. Thus, G and J may exchange places, or F and A, but you cannot exchange G and C, or F and D, because in one case they are both white and in the other case both black. Can you bring about the required arrangement in seventeen exchanges?

It cannot be done in fewer moves. The puzzle is really much easier than it looks, if properly attacked.

Sources:Topics:Combinatorics -> Invariants Logic -> Reasoning / Logic Combinatorics -> Case Analysis / Checking Cases -> Processes / Procedures Combinatorics -> Case Analysis / Checking Cases -> Processes / Procedures Puzzles and Rebuses- Amusements in Mathematics, Henry Ernest Dudeney Question 234

-

THE GRAND TOUR

One of the everyday puzzles of life is the working out of routes. If you are taking a holiday on your bicycle, or a motor tour, there always arises the question of how you are to make the best of your time and other resources. You have determined to get as far as some particular place, to include visits to such-and-such a town, to try to see something of special interest elsewhere, and perhaps to try to look up an old friend at a spot that will not take you much out of your way. Then you have to plan your route so as to avoid bad roads, uninteresting country, and, if possible, the necessity of a return by the same way that you went. With a map before you, the interesting puzzle is attacked and solved. I will present a little poser based on these lines.

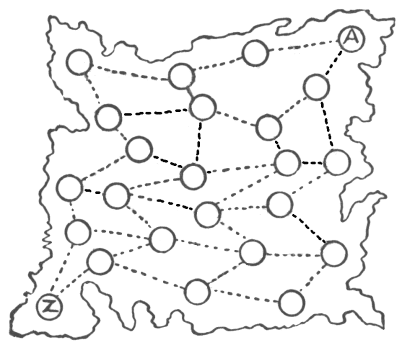

I give a rough map of a country—it is not necessary to say what particular country—the circles representing towns and the dotted lines the railways connecting them. Now there lived in the town marked A a man who was born there, and during the whole of his life had never once left his native place. From his youth upwards he had been very industrious, sticking incessantly to his trade, and had no desire whatever to roam abroad. However, on attaining his fiftieth birthday he decided to see something of his country, and especially to pay a visit to a very old friend living at the town marked Z. What he proposed was this: that he would start from his home, enter every town once and only once, and finish his journey at Z. As he made up his mind to perform this grand tour by rail only, he found it rather a puzzle to work out his route, but he at length succeeded in doing so. How did he manage it? Do not forget that every town has to be visited once, and not more than once.

Sources:Topics:Combinatorics -> Combinatorial Geometry Combinatorics -> Graph Theory Logic -> Reasoning / Logic Combinatorics -> Case Analysis / Checking Cases -> Processes / Procedures Puzzles and Rebuses

Sources:Topics:Combinatorics -> Combinatorial Geometry Combinatorics -> Graph Theory Logic -> Reasoning / Logic Combinatorics -> Case Analysis / Checking Cases -> Processes / Procedures Puzzles and Rebuses- Amusements in Mathematics, Henry Ernest Dudeney Question 250

-

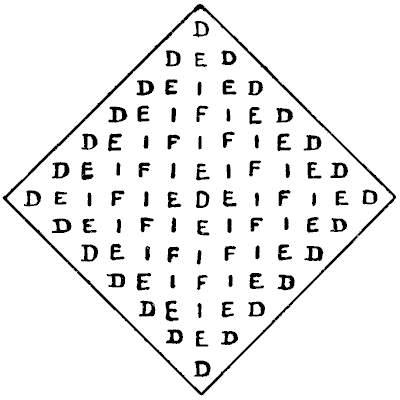

THE DEIFIED PUZZLE

In how many different ways may the word DEIFIED be read in this arrangement under the same conditions as in the last puzzle, with the addition that you can use any letters twice in the same reading? Sources:

Sources:

- Amusements in Mathematics, Henry Ernest Dudeney Question 257

-

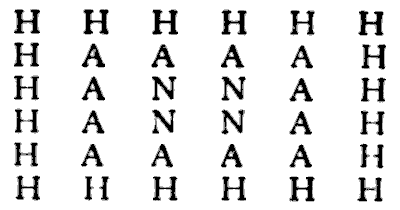

HANNAH'S PUZZLE

A man was in love with a young lady whose Christian name was Hannah. When he asked her to be his wife she wrote down the letters of her name in this manner:— and promised that she would be his if he could tell her correctly in how many different ways it was possible to spell out her name, always passing from one letter to another that was adjacent. Diagonal steps are here allowed. Whether she did this merely to tease him or to test his cleverness is not recorded, but it is satisfactory to know that he succeeded. Would you have been equally successful? Take your pencil and try. You may start from any of the H's and go backwards or forwards and in any direction, so long as all the letters in a spelling are adjoining one another. How many ways are there, no two exactly alike?

Sources:

and promised that she would be his if he could tell her correctly in how many different ways it was possible to spell out her name, always passing from one letter to another that was adjacent. Diagonal steps are here allowed. Whether she did this merely to tease him or to test his cleverness is not recorded, but it is satisfactory to know that he succeeded. Would you have been equally successful? Take your pencil and try. You may start from any of the H's and go backwards or forwards and in any direction, so long as all the letters in a spelling are adjoining one another. How many ways are there, no two exactly alike?

Sources:

- Amusements in Mathematics, Henry Ernest Dudeney Question 259

-

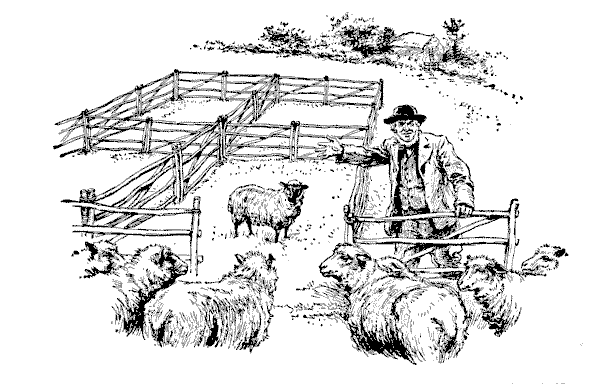

THOSE FIFTEEN SHEEP

A certain cyclopædia has the following curious problem, I am told: "Place fifteen sheep in four pens so that there shall be the same number of sheep in each pen." No answer whatever is vouchsafed, so I thought I would investigate the matter. I saw that in dealing with apples or bricks the thing would appear to be quite impossible, since four times any number must be an even number, while fifteen is an odd number. I thought, therefore, that there must be some quality peculiar to the sheep that was not generally known. So I decided to interview some farmers on the subject. The first one pointed out that if we put one pen inside another, like the rings of a target, and placed all sheep in the smallest pen, it would be all right. But I objected to this, because you admittedly place all the sheep in one pen, not in four pens. The second man said that if I placed four sheep in each of three pens and three sheep in the last pen (that is fifteen sheep in all), and one of the ewes in the last pen had a lamb during the night, there would be the same number in each pen in the morning. This also failed to satisfy me. The third farmer said, "I've got four hurdle pens down in one of my fields, and a small flock of wethers, so if you will just step down with me I will show you how it is done." The illustration depicts my friend as he is about to demonstrate the matter to me. His lucid explanation was evidently that which was in the mind of the writer of the article in the cyclopædia. What was it? Can you place those fifteen sheep?

Sources:Topics:Algebra -> Word Problems Logic -> Reasoning / Logic Combinatorics -> Case Analysis / Checking Cases -> Processes / Procedures Puzzles and Rebuses

The third farmer said, "I've got four hurdle pens down in one of my fields, and a small flock of wethers, so if you will just step down with me I will show you how it is done." The illustration depicts my friend as he is about to demonstrate the matter to me. His lucid explanation was evidently that which was in the mind of the writer of the article in the cyclopædia. What was it? Can you place those fifteen sheep?

Sources:Topics:Algebra -> Word Problems Logic -> Reasoning / Logic Combinatorics -> Case Analysis / Checking Cases -> Processes / Procedures Puzzles and Rebuses- Amusements in Mathematics, Henry Ernest Dudeney Question 262