Combinatorics, Case Analysis / Checking Cases, Processes / Procedures

Case analysis is a problem-solving technique where a problem is divided into several distinct, exhaustive cases. Each case is then analyzed separately to arrive at a solution or proof. Questions suitable for this involve conditions that naturally split the problem into different scenarios.

-

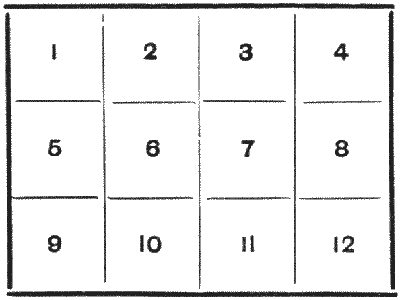

THE FOUR POSTAGE STAMPS

"It is as easy as counting," is an expression one sometimes hears. But mere counting may be puzzling at times. Take the following simple example. Suppose you have just bought twelve postage stamps, in this form—three by four—and a friend asks you to oblige him with four stamps, all joined together—no stamp hanging on by a mere corner. In how many different ways is it possible for you to tear off those four stamps? You see, you can give him `1, 2, 3, 4`, or `2, 3, 6, 7`, or `1, 2, 3, 6`, or `1, 2, 3, 7`, or `2, 3, 4, 8`, and so on. Can you count the number of different ways in which those four stamps might be delivered? There are not many more than fifty ways, so it is not a big count. Can you get the exact number?

Sources:

"It is as easy as counting," is an expression one sometimes hears. But mere counting may be puzzling at times. Take the following simple example. Suppose you have just bought twelve postage stamps, in this form—three by four—and a friend asks you to oblige him with four stamps, all joined together—no stamp hanging on by a mere corner. In how many different ways is it possible for you to tear off those four stamps? You see, you can give him `1, 2, 3, 4`, or `2, 3, 6, 7`, or `1, 2, 3, 6`, or `1, 2, 3, 7`, or `2, 3, 4, 8`, and so on. Can you count the number of different ways in which those four stamps might be delivered? There are not many more than fifty ways, so it is not a big count. Can you get the exact number?

Sources:

- Amusements in Mathematics, Henry Ernest Dudeney Question 285

-

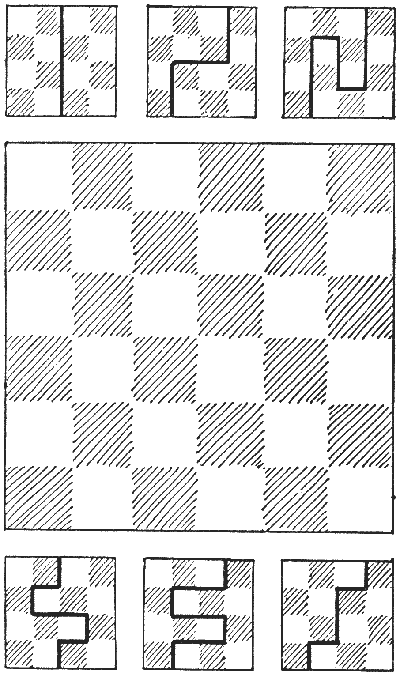

CHEQUERED BOARD DIVISIONS

I recently asked myself the question: In how many different ways may a chessboard be divided into two parts of the same size and shape by cuts along the lines dividing the squares? The problem soon proved to be both fascinating and bristling with difficulties. I present it in a simplified form, taking a board of smaller dimensions. It is obvious that a board of four squares can only be so divided in one way—by a straight cut down the centre—because we shall not count reversals and reflections as different. In the case of a board of sixteen squares—four by four—there are just six different ways. I have given all these in the diagram, and the reader will not find any others. Now, take the larger board of thirty-six squares, and try to discover in how many ways it may be cut into two parts of the same size and shape.

Sources:Topics:Combinatorics -> Case Analysis / Checking Cases -> Processes / Procedures Combinatorics -> Combinatorial Geometry -> Cut a Shape / Dissection Problems

It is obvious that a board of four squares can only be so divided in one way—by a straight cut down the centre—because we shall not count reversals and reflections as different. In the case of a board of sixteen squares—four by four—there are just six different ways. I have given all these in the diagram, and the reader will not find any others. Now, take the larger board of thirty-six squares, and try to discover in how many ways it may be cut into two parts of the same size and shape.

Sources:Topics:Combinatorics -> Case Analysis / Checking Cases -> Processes / Procedures Combinatorics -> Combinatorial Geometry -> Cut a Shape / Dissection Problems- Amusements in Mathematics, Henry Ernest Dudeney Question 288

-

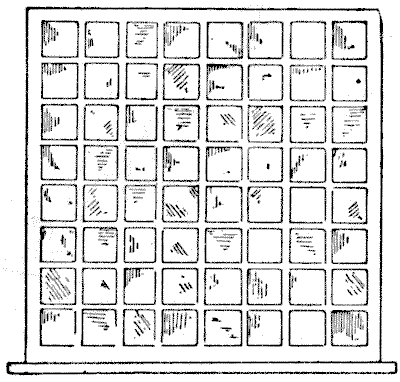

THE ABBOT'S WINDOW

Once upon a time the Lord Abbot of St. Edmondsbury, in consequence of "devotions too strong for his head," fell sick and was unable to leave his bed. As he lay awake, tossing his head restlessly from side to side, the attentive monks noticed that something was disturbing his mind; but nobody dared ask what it might be, for the abbot was of a stern disposition, and never would brook inquisitiveness. Suddenly he called for Father John, and that venerable monk was soon at the bedside.

"Father John," said the Abbot, "dost thou know that I came into this wicked world on a Christmas Even?

"The monk nodded assent.

"And have I not often told thee that, having been born on Christmas Even, I have no love for the things that are odd? Look there!"

The Abbot pointed to the large dormitory window, of which I give a sketch. The monk looked, and was perplexed.

"Dost thou not see that the sixty-four lights add up an even number vertically and horizontally, but that all the diagonal lines, except fourteen are of a number that is odd? Why is this?"

"Of a truth, my Lord Abbot, it is of the very nature of things, and cannot be changed."

"Nay, but it shall be changed. I command thee that certain of the lights be closed this day, so that every line shall have an even number of lights. See thou that this be done without delay, lest the cellars be locked up for a month and other grievous troubles befall thee."

Father John was at his wits' end, but after consultation with one who was learned in strange mysteries, a way was found to satisfy the whim of the Lord Abbot. Which lights were blocked up, so that those which remained added up an even number in every line horizontally, vertically, and diagonally, while the least possible obstruction of light was caused?

Sources:Topics:Logic -> Reasoning / Logic Combinatorics -> Case Analysis / Checking Cases -> Processes / Procedures- Amusements in Mathematics, Henry Ernest Dudeney Question 292

-

THE CHINESE CHESSBOARD

Into how large a number of different pieces may the chessboard be cut (by cuts along the lines only), no two pieces being exactly alike? Remember that the arrangement of black and white constitutes a difference. Thus, a single black square will be different from a single white square, a row of three containing two white squares will differ from a row of three containing two black, and so on. If two pieces cannot be placed on the table so as to be exactly alike, they count as different. And as the back of the board is plain, the pieces cannot be turned over. Sources:- Amusements in Mathematics, Henry Ernest Dudeney Question 293

-

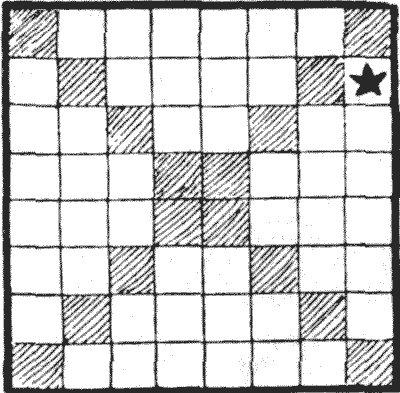

THE EIGHT STARS

The puzzle in this case is to place eight stars in the diagram so that no star shall be in line with another star horizontally, vertically, or diagonally. One star is already placed, and that must not be moved, so there are only seven for the reader now to place. But you must not place a star on any one of the shaded squares. There is only one way of solving this little puzzle.

Sources:Topics:Combinatorics -> Case Analysis / Checking Cases -> Processes / Procedures Puzzles and Rebuses

The puzzle in this case is to place eight stars in the diagram so that no star shall be in line with another star horizontally, vertically, or diagonally. One star is already placed, and that must not be moved, so there are only seven for the reader now to place. But you must not place a star on any one of the shaded squares. There is only one way of solving this little puzzle.

Sources:Topics:Combinatorics -> Case Analysis / Checking Cases -> Processes / Procedures Puzzles and Rebuses- Amusements in Mathematics, Henry Ernest Dudeney Question 301

-

UNDER THE VEIL

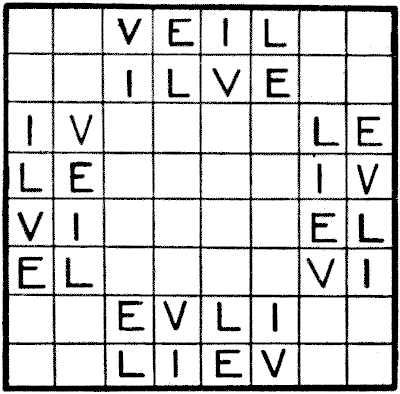

If the reader will examine the above diagram, he will see that I have so placed eight V's, eight E's, eight I's, and eight L's in the diagram that no letter is in line with a similar one horizontally, vertically, or diagonally. Thus, no V is in line with another V, no E with another E, and so on. There are a great many different ways of arranging the letters under this condition. The puzzle is to find an arrangement that produces the greatest possible number of four-letter words, reading upwards and downwards, backwards and forwards, or diagonally. All repetitions count as different words, and the five variations that may be used are: VEIL, VILE, LEVI, LIVE, and EVIL.

This will be made perfectly clear when I say that the above arrangement scores eight, because the top and bottom row both give VEIL; the second and seventh columns both give VEIL; and the two diagonals, starting from the L in the 5th row and E in the 8th row, both give LIVE and EVIL. There are therefore eight different readings of the words in all.

This difficult word puzzle is given as an example of the use of chessboard analysis in solving such things. Only a person who is familiar with the "Eight Queens" problem could hope to solve it.

Sources:Topics:Combinatorics -> Case Analysis / Checking Cases -> Processes / Procedures Combinatorics -> Colorings -> Chessboard Coloring Puzzles and Rebuses- Amusements in Mathematics, Henry Ernest Dudeney Question 303

-

BACHET'S SQUARE

One of the oldest card puzzles is by Claude Caspar Bachet de Méziriac, first published, I believe, in the `1624` edition of his work. Rearrange the sixteen court cards (including the aces) in a square so that in no row of four cards, horizontal, vertical, or diagonal, shall be found two cards of the same suit or the same value. This in itself is easy enough, but a point of the puzzle is to find in how many different ways this may be done. The eminent French mathematician A. Labosne, in his modern edition of Bachet, gives the answer incorrectly. And yet the puzzle is really quite easy. Any arrangement produces seven more by turning the square round and reflecting it in a mirror. These are counted as different by Bachet.

Note "row of four cards," so that the only diagonals we have here to consider are the two long ones.

Sources:- Amusements in Mathematics, Henry Ernest Dudeney Question 304

-

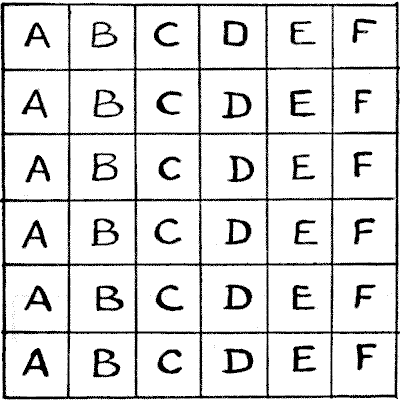

THE THIRTY-SIX LETTER BLOCKS

The illustration represents a box containing thirty-six letter-blocks. The puzzle is to rearrange these blocks so that no A shall be in a line vertically, horizontally, or diagonally with another A, no B with another B, no C with another C, and so on. You will find it impossible to get all the letters into the box under these conditions, but the point is to place as many as possible. Of course no letters other than those shown may be used.

Sources:Topics:Combinatorics -> Pigeonhole Principle Logic -> Reasoning / Logic Combinatorics -> Case Analysis / Checking Cases -> Processes / Procedures

The illustration represents a box containing thirty-six letter-blocks. The puzzle is to rearrange these blocks so that no A shall be in a line vertically, horizontally, or diagonally with another A, no B with another B, no C with another C, and so on. You will find it impossible to get all the letters into the box under these conditions, but the point is to place as many as possible. Of course no letters other than those shown may be used.

Sources:Topics:Combinatorics -> Pigeonhole Principle Logic -> Reasoning / Logic Combinatorics -> Case Analysis / Checking Cases -> Processes / Procedures- Amusements in Mathematics, Henry Ernest Dudeney Question 305

-

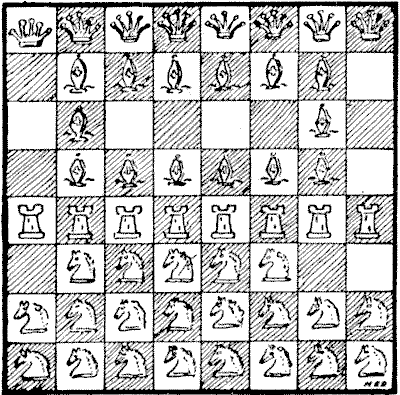

THE CROWDED CHESSBOARD

The puzzle is to rearrange the fifty-one pieces on the chessboard so that no queen shall attack another queen, no rook attack another rook, no bishop attack another bishop, and no knight attack another knight. No notice is to be taken of the intervention of pieces of another type from that under consideration—that is, two queens will be considered to attack one another although there may be, say, a rook, a bishop, and a knight between them. And so with the rooks and bishops. It is not difficult to dispose of each type of piece separately; the difficulty comes in when you have to find room for all the arrangements on the board simultaneously.

Sources:Topics:Combinatorics -> Pigeonhole Principle Combinatorics -> Case Analysis / Checking Cases -> Processes / Procedures

The puzzle is to rearrange the fifty-one pieces on the chessboard so that no queen shall attack another queen, no rook attack another rook, no bishop attack another bishop, and no knight attack another knight. No notice is to be taken of the intervention of pieces of another type from that under consideration—that is, two queens will be considered to attack one another although there may be, say, a rook, a bishop, and a knight between them. And so with the rooks and bishops. It is not difficult to dispose of each type of piece separately; the difficulty comes in when you have to find room for all the arrangements on the board simultaneously.

Sources:Topics:Combinatorics -> Pigeonhole Principle Combinatorics -> Case Analysis / Checking Cases -> Processes / Procedures- Amusements in Mathematics, Henry Ernest Dudeney Question 306

-

THE GENTLE ART OF STAMP-LICKING

The Insurance Act is a most prolific source of entertaining puzzles, particularly entertaining if you happen to be among the exempt. One's initiation into the gentle art of stamp-licking suggests the following little poser: If you have a card divided into sixteen spaces (`4` × `4`), and are provided with plenty of stamps of the values `1`d., `2`d., `3`d., `4`d., and `5`d., what is the greatest value that you can stick on the card if the Chancellor of the Exchequer forbids you to place any stamp in a straight line (that is, horizontally, vertically, or diagonally) with another stamp of similar value? Of course, only one stamp can be affixed in a space. The reader will probably find, when he sees the solution, that, like the stamps themselves, he is licked He will most likely be twopence short of the maximum. A friend asked the Post Office how it was to be done; but they sent him to the Customs and Excise officer, who sent him to the Insurance Commissioners, who sent him to an approved society, who profanely sent him—but no matter. Sources:- Amusements in Mathematics, Henry Ernest Dudeney Question 308