Combinatorics, Case Analysis / Checking Cases, Processes / Procedures

Case analysis is a problem-solving technique where a problem is divided into several distinct, exhaustive cases. Each case is then analyzed separately to arrive at a solution or proof. Questions suitable for this involve conditions that naturally split the problem into different scenarios.

-

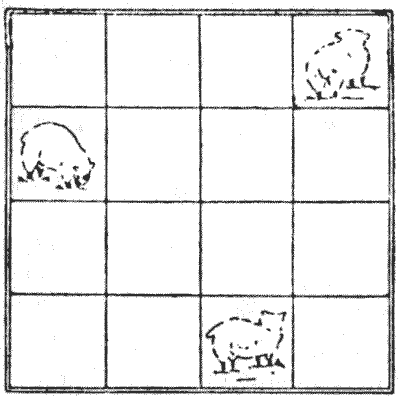

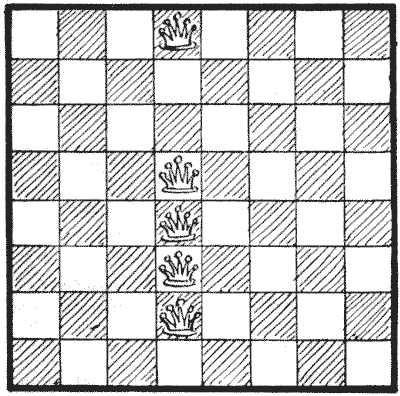

THE THREE SHEEP

A farmer had three sheep and an arrangement of sixteen pens, divided off by hurdles in the manner indicated in the illustration. In how many different ways could he place those sheep, each in a separate pen, so that every pen should be either occupied or in line (horizontally, vertically, or diagonally) with at least one sheep? I have given one arrangement that fulfils the conditions. How many others can you find? Mere reversals and reflections must not be counted as different. The reader may regard the sheep as queens. The problem is then to place the three queens so that every square shall be either occupied or attacked by at least one queen—in the maximum number of different ways.

Sources:

A farmer had three sheep and an arrangement of sixteen pens, divided off by hurdles in the manner indicated in the illustration. In how many different ways could he place those sheep, each in a separate pen, so that every pen should be either occupied or in line (horizontally, vertically, or diagonally) with at least one sheep? I have given one arrangement that fulfils the conditions. How many others can you find? Mere reversals and reflections must not be counted as different. The reader may regard the sheep as queens. The problem is then to place the three queens so that every square shall be either occupied or attacked by at least one queen—in the maximum number of different ways.

Sources:

- Amusements in Mathematics, Henry Ernest Dudeney Question 310

-

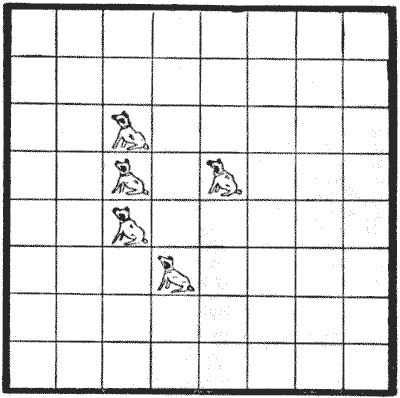

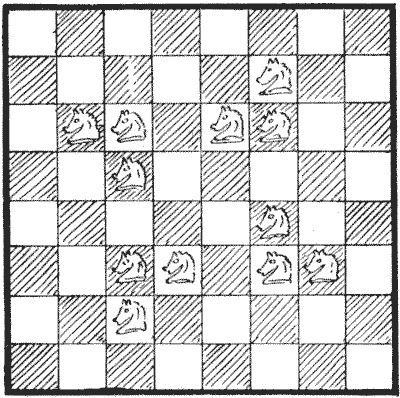

THE FIVE DOGS PUZZLE

In `1863`, C.F. de Jaenisch first discussed the "Five Queens Puzzle"—to place five queens on the chessboard so that every square shall be attacked or occupied—which was propounded by his friend, a "Mr. de R." Jaenisch showed that if no queen may attack another there are ninety-one different ways of placing the five queens, reversals and reflections not counting as different. If the queens may attack one another, I have recorded hundreds of ways, but it is not practicable to enumerate them exactly. The illustration is supposed to represent an arrangement of sixty-four kennels. It will be seen that five kennels each contain a dog, and on further examination it will be seen that every one of the sixty-four kennels is in a straight line with at least one dog—either horizontally, vertically, or diagonally. Take any kennel you like, and you will find that you can draw a straight line to a dog in one or other of the three ways mentioned. The puzzle is to replace the five dogs and discover in just how many different ways they may be placed in five kennels in a straight row, so that every kennel shall always be in line with at least one dog. Reversals and reflections are here counted as different.

Sources:

The illustration is supposed to represent an arrangement of sixty-four kennels. It will be seen that five kennels each contain a dog, and on further examination it will be seen that every one of the sixty-four kennels is in a straight line with at least one dog—either horizontally, vertically, or diagonally. Take any kennel you like, and you will find that you can draw a straight line to a dog in one or other of the three ways mentioned. The puzzle is to replace the five dogs and discover in just how many different ways they may be placed in five kennels in a straight row, so that every kennel shall always be in line with at least one dog. Reversals and reflections are here counted as different.

Sources:

- Amusements in Mathematics, Henry Ernest Dudeney Question 311

-

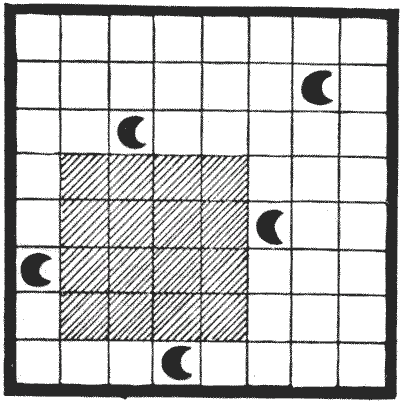

THE FIVE CRESCENTS OF BYZANTIUM

When Philip of Macedon, the father of Alexander the Great, found himself confronted with great difficulties in the siege of Byzantium, he set his men to undermine the walls. His desires, however, miscarried, for no sooner had the operations been begun than a crescent moon suddenly appeared in the heavens and discovered his plans to his adversaries. The Byzantines were naturally elated, and in order to show their gratitude they erected a statue to Diana, and the crescent became thenceforward a symbol of the state. In the temple that contained the statue was a square pavement composed of sixty-four large and costly tiles. These were all plain, with the exception of five, which bore the symbol of the crescent. These five were for occult reasons so placed that every tile should be watched over by (that is, in a straight line, vertically, horizontally, or diagonally with) at least one of the crescents. The arrangement adopted by the Byzantine architect was as follows:—

Now, to cover up one of these five crescents was a capital offence, the death being something very painful and lingering. But on a certain occasion of festivity it was necessary to lay down on this pavement a square carpet of the largest dimensions possible, and I have shown in the illustration by dark shading the largest dimensions that would be available.

The puzzle is to show how the architect, if he had foreseen this question of the carpet, might have so arranged his five crescent tiles in accordance with the required conditions, and yet have allowed for the largest possible square carpet to be laid down without any one of the five crescent tiles being covered, or any portion of them.

Sources:Topics:Combinatorics -> Case Analysis / Checking Cases -> Processes / Procedures Combinatorics -> Combinatorial Geometry -> Grid Paper Geometry / Lattice Geometry Puzzles and Rebuses- Amusements in Mathematics, Henry Ernest Dudeney Question 312

-

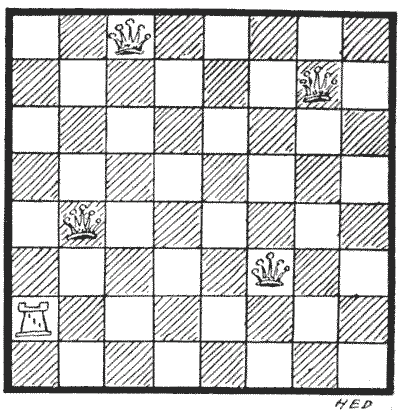

QUEENS AND BISHOP PUZZLE

It will be seen that every square of the board is either occupied or attacked. The puzzle is to substitute a bishop for the rook on the same square, and then place the four queens on other squares so that every square shall again be either occupied or attacked.

Sources:Topics:Logic -> Reasoning / Logic Combinatorics -> Case Analysis / Checking Cases -> Processes / Procedures Puzzles and Rebuses

Sources:Topics:Logic -> Reasoning / Logic Combinatorics -> Case Analysis / Checking Cases -> Processes / Procedures Puzzles and Rebuses- Amusements in Mathematics, Henry Ernest Dudeney Question 313

-

THE HAT-PEG PUZZLE

Here is a five-queen puzzle that I gave in a fanciful dress in `1897`. As the queens were there represented as hats on sixty-four pegs, I will keep to the title, "The Hat-Peg Puzzle." It will be seen that every square is occupied or attacked. The puzzle is to remove one queen to a different square so that still every square is occupied or attacked, then move a second queen under a similar condition, then a third queen, and finally a fourth queen. After the fourth move every square must be attacked or occupied, but no queen must then attack another. Of course, the moves need not be "queen moves;" you can move a queen to any part of the board.

Sources:Topics:Combinatorics -> Case Analysis / Checking Cases -> Processes / Procedures Puzzles and Rebuses

to a different square so that still every square is occupied or attacked, then move a second queen under a similar condition, then a third queen, and finally a fourth queen. After the fourth move every square must be attacked or occupied, but no queen must then attack another. Of course, the moves need not be "queen moves;" you can move a queen to any part of the board.

Sources:Topics:Combinatorics -> Case Analysis / Checking Cases -> Processes / Procedures Puzzles and Rebuses- Amusements in Mathematics, Henry Ernest Dudeney Question 315

-

THE KNIGHT-GUARDS

The knight is the irresponsible low comedian of the chessboard. "He is a very uncertain, sneaking, and demoralizing rascal," says an American writer. "He can only move two squares, but makes up in the quality of his locomotion for its quantity, for he can spring one square sideways and one forward simultaneously, like a cat; can stand on one leg in the middle of the board and jump to any one of eight squares he chooses; can get on one side of a fence and blackguard three or four men on the other; has an objectionable way of inserting himself in safe places where he can scare the king and compel him to move, and then gobble a queen. For pure cussedness the knight has no equal, and when you chase him out of one hole he skips into another." Attempts have been made over and over again to obtain a short, simple, and exact definition of the move of the knight—without success. It really consists in moving one square like a rook, and then another square like a bishop—the two operations being done in one leap, so that it does not matter whether the first square passed over is occupied by another piece or not. It is, in fact, the only leaping move in chess. But difficult as it is to define, a child can learn it by inspection in a few minutes.

I have shown in the diagram how twelve knights (the fewest possible that will perform the feat) may be placed on the chessboard so that every square is either occupied or attacked by a knight. Examine every square in turn, and you will find that this is so. Now, the puzzle in this case is to discover what is the smallest possible number of knights that is required in order that every square shall be either occupied or attacked, and every knight protected by another knight. And how would you arrange them? It will be found that of the twelve shown in the diagram only four are thus protected by being a knight's move from another knight.

Sources:Topics:Combinatorics -> Combinatorial Geometry Logic -> Reasoning / Logic Combinatorics -> Case Analysis / Checking Cases -> Processes / Procedures- Amusements in Mathematics, Henry Ernest Dudeney Question 319

-

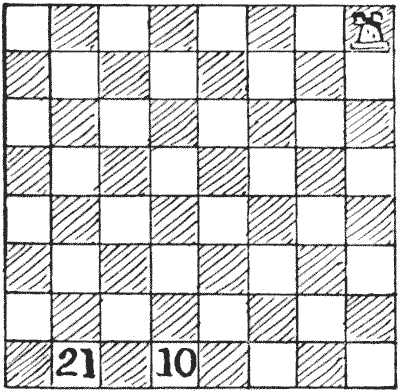

THE ROOK'S JOURNEY

This puzzle I call "The Rook's Journey," because the word "tour" (derived from a turner's wheel) implies that we return to the point from which we set out, and we do not do this in the present case. We should not be satisfied with a personally conducted holiday tour that ended by leaving us, say, in the middle of the Sahara. The rook here makes twenty-one moves, in the course of which journey it visits every square of the board once and only once, stopping at the square marked `10` at the end of its tenth move, and ending at the square marked `21`. Two consecutive moves cannot be made in the same direction—that is to say, you must make a turn after every move. Sources:Topics:Logic -> Reasoning / Logic Combinatorics -> Case Analysis / Checking Cases -> Processes / Procedures Combinatorics -> Combinatorial Geometry -> Grid Paper Geometry / Lattice Geometry Puzzles and Rebuses

Sources:Topics:Logic -> Reasoning / Logic Combinatorics -> Case Analysis / Checking Cases -> Processes / Procedures Combinatorics -> Combinatorial Geometry -> Grid Paper Geometry / Lattice Geometry Puzzles and Rebuses- Amusements in Mathematics, Henry Ernest Dudeney Question 321

-

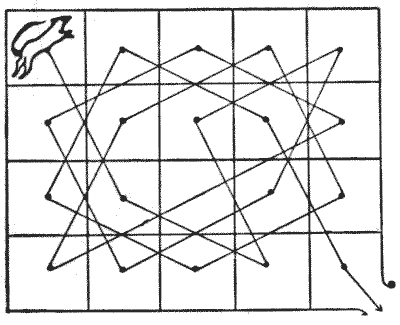

THE GREYHOUND PUZZLE

In this puzzle the twenty kennels do not communicate with one another by doors, but are divided off by a low wall. The solitary occupant is the greyhound which lives in the kennel in the top left-hand corner. When he is allowed his liberty he has to obtain it by visiting every kennel once and only once in a series of knight's moves, ending at the bottom right-hand corner, which is open to the world. The lines in the above diagram show one solution. The puzzle is to discover in how many different ways the greyhound may thus make his exit from his corner kennel. Sources:

Sources:

- Amusements in Mathematics, Henry Ernest Dudeney Question 336

-

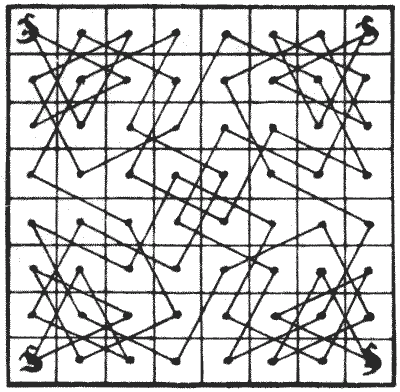

THE FOUR KANGAROOS

In introducing a little Commonwealth problem, I must first explain that the diagram represents the sixty-four fields, all properly fenced off from one another, of an Australian settlement, though I need hardly say that our kith and kin "down under" always do set out their land in this methodical and exact manner. It will be seen that in every one of the four corners is a kangaroo. Why kangaroos have a marked preference for corner plots has never been satisfactorily explained, and it would be out of place to discuss the point here. I should also add that kangaroos, as is well known, always leap in what we call "knight's moves." In fact, chess players would probably have adopted the better term "kangaroo's move" had not chess been invented before kangaroos.

In introducing a little Commonwealth problem, I must first explain that the diagram represents the sixty-four fields, all properly fenced off from one another, of an Australian settlement, though I need hardly say that our kith and kin "down under" always do set out their land in this methodical and exact manner. It will be seen that in every one of the four corners is a kangaroo. Why kangaroos have a marked preference for corner plots has never been satisfactorily explained, and it would be out of place to discuss the point here. I should also add that kangaroos, as is well known, always leap in what we call "knight's moves." In fact, chess players would probably have adopted the better term "kangaroo's move" had not chess been invented before kangaroos.The puzzle is simply this. One morning each kangaroo went for his morning hop, and in sixteen consecutive knight's leaps visited just fifteen different fields and jumped back to his corner. No field was visited by more than one of the kangaroos. The diagram shows how they arranged matters. What you are asked to do is to show how they might have performed the feat without any kangaroo ever crossing the horizontal line in the middle of the square that divides the board into two equal parts.

Sources:Topics:Combinatorics -> Graph Theory Combinatorics -> Case Analysis / Checking Cases -> Processes / Procedures Combinatorics -> Colorings -> Chessboard Coloring Combinatorics -> Combinatorial Geometry -> Grid Paper Geometry / Lattice Geometry- Amusements in Mathematics, Henry Ernest Dudeney Question 337

-

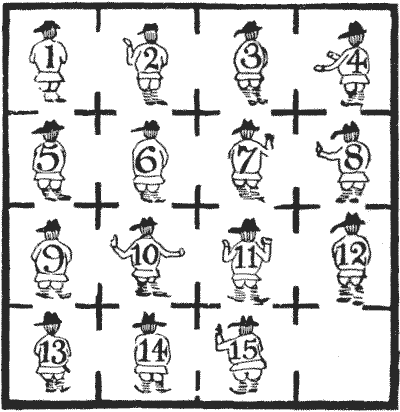

EXERCISE FOR PRISONERS

The following is the plan of the north wing of a certain gaol, showing the sixteen cells all communicating by open doorways. Fifteen prisoners were numbered and arranged in the cells as shown. They were allowed to change their cells as much as they liked, but if two prisoners were ever in the same cell together there was a severe punishment promised them.

Now, in order to reduce their growing obesity, and to combine physical exercise with mental recreation, the prisoners decided, on the suggestion of one of their number who was interested in knight's tours, to try to form themselves into a perfect knight's path without breaking the prison regulations, and leaving the bottom right-hand corner cell vacant, as originally. The joke of the matter is that the arrangement at which they arrived was as follows:—

8 3 12 1 11 14 9 6 4 7 2 13 15 10 5 The warders failed to detect the important fact that the men could not possibly get into this position without two of them having been at some time in the same cell together. Make the attempt with counters on a ruled diagram, and you will find that this is so. Otherwise the solution is correct enough, each member being, as required, a knight's move from the preceding number, and the original corner cell vacant.

The puzzle is to start with the men placed as in the illustration and show how it might have been done in the fewest moves, while giving a complete rest to as many prisoners as possible.

As there is never more than one vacant cell for a man to enter, it is only necessary to write down the numbers of the men in the order in which they move. It is clear that very few men can be left throughout in their cells undisturbed, but I will leave the solver to discover just how many, as this is a very essential part of the puzzle.

Sources:Topics:Combinatorics -> Graph Theory Combinatorics -> Case Analysis / Checking Cases -> Processes / Procedures- Amusements in Mathematics, Henry Ernest Dudeney Question 343