Combinatorics, Case Analysis / Checking Cases, Processes / Procedures

This category covers problems involving sequences of operations or steps that evolve over time or iterations. Questions might ask about the outcome of a process, whether it terminates, or properties of its state after a certain number of steps. Often related to algorithms or invariants.

-

KING ARTHUR'S KNIGHTS

King Arthur sat at the Round Table on three successive evenings with his knights—Beleobus, Caradoc, Driam, Eric, Floll, and Galahad—but on no occasion did any person have as his neighbour one who had before sat next to him. On the first evening they sat in alphabetical order round the table. But afterwards King Arthur arranged the two next sittings so that he might have Beleobus as near to him as possible and Galahad as far away from him as could be managed. How did he seat the knights to the best advantage, remembering that rule that no knight may have the same neighbour twice? Sources:- Amusements in Mathematics, Henry Ernest Dudeney Question 263

-

THE WRONG HATS

"One of the most perplexing things I have come across lately," said Mr. Wilson, "is this. Eight men had been dining not wisely but too well at a certain London restaurant. They were the last to leave, but not one man was in a condition to identify his own hat. Now, considering that they took their hats at random, what are the chances that every man took a hat that did not belong to him?"

"The first thing," said Mr. Waterson, "is to see in how many different ways the eight hats could be taken."

"That is quite easy," Mr. Stubbs explained. "Multiply together the numbers, `1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7`, and `8`. Let me see—half a minute—yes; there are `40,320` different ways."

"Now all you've got to do is to see in how many of these cases no man has his own hat," said Mr. Waterson."

Thank you, I'm not taking any," said Mr. Packhurst. "I don't envy the man who attempts the task of writing out all those forty-thousand-odd cases and then picking out the ones he wants."

They all agreed that life is not long enough for that sort of amusement; and as nobody saw any other way of getting at the answer, the matter was postponed indefinitely. Can you solve the puzzle?

Sources:Topics:Combinatorics -> Induction (Mathematical Induction) Combinatorics -> Case Analysis / Checking Cases -> Processes / Procedures- Amusements in Mathematics, Henry Ernest Dudeney Question 267

-

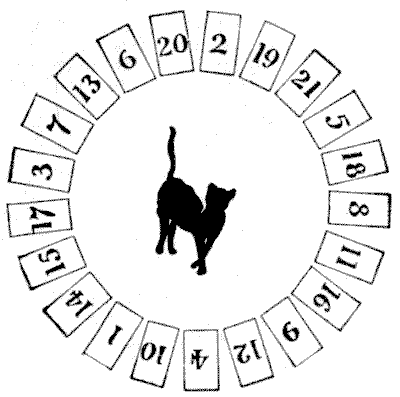

THE MOUSE-TRAP PUZZLE

This is a modern version, with a difference, of an old puzzle of the same name. Number twenty-one cards, `1, 2, 3`, etc., up to `21`, and place them in a circle in the particular order shown in the illustration. These cards represent mice. You start from any card, calling that card "one," and count, "one, two, three," etc., in a clockwise direction, and when your count agrees with the number on the card, you have made a "catch," and you remove the card. Then start at the next card, calling that "one," and try again to make another "catch." And so on. Supposing you start at `18`, calling that card "one," your first "catch" will be `19`. Remove `19` and your next "catch" is `10`. Remove `10` and your next "catch" is `1`. Remove the `1`, and if you count up to `21` (you must never go beyond), you cannot make another "catch." Now, the ideal is to "catch" all the twenty-one mice, but this is not here possible, and if it were it would merely require twenty-one different trials, at the most, to succeed. But the reader may make any two cards change places before he begins. Thus, you can change the `6` with the `2`, or the `7` with the `11`, or any other pair. This can be done in several ways so as to enable you to "catch" all the twenty-one mice, if you then start at the right place. You may never pass over a "catch"; you must always remove the card and start afresh.

Sources:

This is a modern version, with a difference, of an old puzzle of the same name. Number twenty-one cards, `1, 2, 3`, etc., up to `21`, and place them in a circle in the particular order shown in the illustration. These cards represent mice. You start from any card, calling that card "one," and count, "one, two, three," etc., in a clockwise direction, and when your count agrees with the number on the card, you have made a "catch," and you remove the card. Then start at the next card, calling that "one," and try again to make another "catch." And so on. Supposing you start at `18`, calling that card "one," your first "catch" will be `19`. Remove `19` and your next "catch" is `10`. Remove `10` and your next "catch" is `1`. Remove the `1`, and if you count up to `21` (you must never go beyond), you cannot make another "catch." Now, the ideal is to "catch" all the twenty-one mice, but this is not here possible, and if it were it would merely require twenty-one different trials, at the most, to succeed. But the reader may make any two cards change places before he begins. Thus, you can change the `6` with the `2`, or the `7` with the `11`, or any other pair. This can be done in several ways so as to enable you to "catch" all the twenty-one mice, if you then start at the right place. You may never pass over a "catch"; you must always remove the card and start afresh.

Sources:

- Amusements in Mathematics, Henry Ernest Dudeney Question 274

-

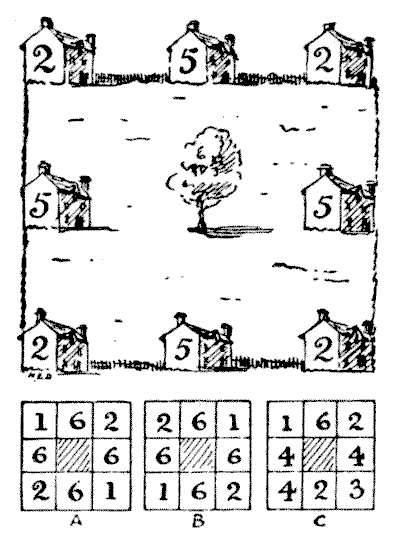

THE EIGHT VILLAS

In one of the outlying suburbs of London a man had a square plot of ground on which he decided to build eight villas, as shown in the illustration, with a common recreation ground in the middle. After the houses were completed, and all or some of them let, he discovered that the number of occupants in the three houses forming a side of the square was in every case nine. He did not state how the occupants were distributed, but I have shown by the numbers on the sides of the houses one way in which it might have happened. The puzzle is to discover the total number of ways in which all or any of the houses might be occupied, so that there should be nine persons on each side. In order that there may be no misunderstanding, I will explain that although B is what we call a reflection of A, these would count as two different arrangements, while C, if it is turned round, will give four arrangements; and if turned round in front of a mirror, four other arrangements. All eight must be counted. Sources:

Sources:

- Amusements in Mathematics, Henry Ernest Dudeney Question 276

-

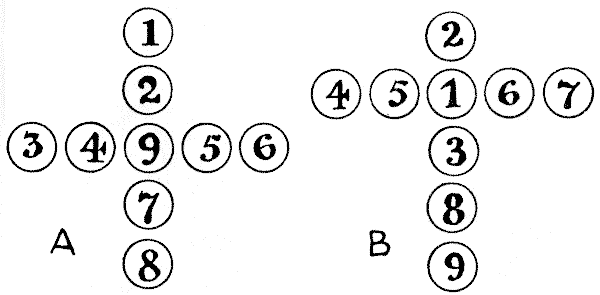

COUNTER CROSSES

All that we need for this puzzle is nine counters, numbered `1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8`, and `9`. It will be seen that in the illustration A these are arranged so as to form a Greek cross, while in the case of B they form a Latin cross. In both cases the reader will find that the sum of the numbers in the upright of the cross is the same as the sum of the numbers in the horizontal arm. It is quite easy to hit on such an arrangement by trial, but the problem is to discover in exactly how many different ways it may be done in each case. Remember that reversals and reflections do not count as different. That is to say, if you turn this page round you get four arrangements of the Greek cross, and if you turn it round again in front of a mirror you will get four more. But these eight are all regarded as one and the same. Now, how many different ways are there in each case? Sources:Topics:Combinatorics -> Product Rule / Rule of Product Combinatorics -> Case Analysis / Checking Cases -> Processes / Procedures Combinatorics -> Number Tables

Sources:Topics:Combinatorics -> Product Rule / Rule of Product Combinatorics -> Case Analysis / Checking Cases -> Processes / Procedures Combinatorics -> Number Tables- Amusements in Mathematics, Henry Ernest Dudeney Question 277

-

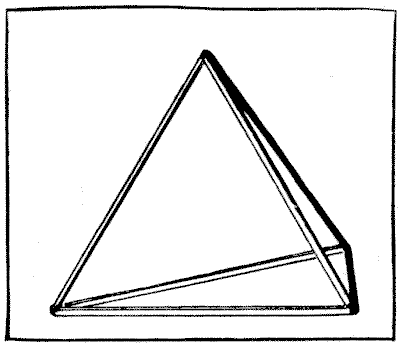

BUILDING THE TETRAHEDRON

I possess a tetrahedron, or triangular pyramid, formed of six sticks glued together, as shown in the illustration. Can you count correctly the number of different ways in which these six sticks might have been stuck together so as to form the pyramid?

Some friends worked at it together one evening, each person providing himself with six lucifer matches to aid his thoughts; but it was found that no two results were the same. You see, if we remove one of the sticks and turn it round the other way, that will be a different pyramid. If we make two of the sticks change places the result will again be different. But remember that every pyramid may be made to stand on either of its four sides without being a different one. How many ways are there altogether?

Sources:Topics:Combinatorics -> Case Analysis / Checking Cases -> Processes / Procedures Geometry -> Solid Geometry / Geometry in Space -> Polyhedra

Sources:Topics:Combinatorics -> Case Analysis / Checking Cases -> Processes / Procedures Geometry -> Solid Geometry / Geometry in Space -> Polyhedra- Amusements in Mathematics, Henry Ernest Dudeney Question 280

-

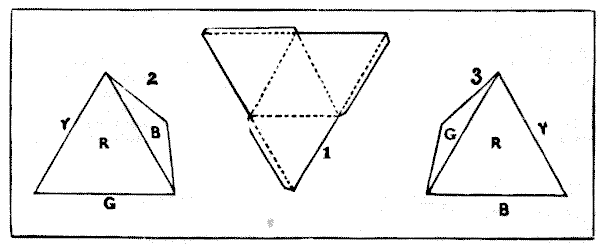

PAINTING A PYRAMID

This puzzle concerns the painting of the four sides of a tetrahedron, or triangular pyramid. If you cut out a piece of cardboard of the triangular shape shown in Fig. `1`, and then cut half through along the dotted lines, it will fold up and form a perfect triangular pyramid. And I would first remind my readers that the primary colours of the solar spectrum are seven—violet, indigo, blue, green, yellow, orange, and red. When I was a child I was taught to remember these by the ungainly word formed by the initials of the colours, "Vibgyor." In how many different ways may the triangular pyramid be coloured, using in every case one, two, three, or four colours of the solar spectrum? Of course a side can only receive a single colour, and no side can be left uncoloured. But there is one point that I must make quite clear. The four sides are not to be regarded as individually distinct. That is to say, if you paint your pyramid as shown in Fig. `2` (where the bottom side is green and the other side that is out of view is yellow), and then paint another in the order shown in Fig. `3`, these are really both the same and count as one way. For if you tilt over No. `2` to the right it will so fall as to represent No. `3`. The avoidance of repetitions of this kind is the real puzzle of the thing. If a coloured pyramid cannot be placed so that it exactly resembles in its colours and their relative order another pyramid, then they are different. Remember that one way would be to colour all the four sides red, another to colour two sides green, and the remaining sides yellow and blue; and so on.

Sources:Topics:Combinatorics -> Case Analysis / Checking Cases -> Processes / Procedures Geometry -> Solid Geometry / Geometry in Space -> Polyhedra

In how many different ways may the triangular pyramid be coloured, using in every case one, two, three, or four colours of the solar spectrum? Of course a side can only receive a single colour, and no side can be left uncoloured. But there is one point that I must make quite clear. The four sides are not to be regarded as individually distinct. That is to say, if you paint your pyramid as shown in Fig. `2` (where the bottom side is green and the other side that is out of view is yellow), and then paint another in the order shown in Fig. `3`, these are really both the same and count as one way. For if you tilt over No. `2` to the right it will so fall as to represent No. `3`. The avoidance of repetitions of this kind is the real puzzle of the thing. If a coloured pyramid cannot be placed so that it exactly resembles in its colours and their relative order another pyramid, then they are different. Remember that one way would be to colour all the four sides red, another to colour two sides green, and the remaining sides yellow and blue; and so on.

Sources:Topics:Combinatorics -> Case Analysis / Checking Cases -> Processes / Procedures Geometry -> Solid Geometry / Geometry in Space -> Polyhedra- Amusements in Mathematics, Henry Ernest Dudeney Question 281

-

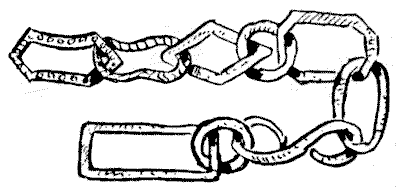

THE ANTIQUARY'S CHAIN

An antiquary possessed a number of curious old links, which he took to a blacksmith, and told him to join together to form one straight piece of chain, with the sole condition that the two circular links were not to be together. The following illustration shows the appearance of the chain and the form of each link. Now, supposing the owner should separate the links again, and then take them to another smith and repeat his former instructions exactly, what are the chances against the links being put together exactly as they were by the first man? Remember that every successive link can be joined on to another in one of two ways, just as you can put a ring on your finger in two ways, or link your forefingers and thumbs in two ways. Sources:Topics:Combinatorics -> Product Rule / Rule of Product Combinatorics -> Case Analysis / Checking Cases -> Processes / Procedures

Sources:Topics:Combinatorics -> Product Rule / Rule of Product Combinatorics -> Case Analysis / Checking Cases -> Processes / Procedures- Amusements in Mathematics, Henry Ernest Dudeney Question 282

-

THE FIFTEEN DOMINOES

In this case we do not use the complete set of twenty-eight dominoes to be found in the ordinary box. We dispense with all those dominoes that have a five or a six on them and limit ourselves to the fifteen that remain, where the double-four is the highest.

In how many different ways may the fifteen dominoes be arranged in a straight line in accordance with the simple rule of the game that a number must always be placed against a similar number—that is, a four against a four, a blank against a blank, and so on? Left to right and right to left of the same arrangement are to be counted as two different ways.

Sources:- Amusements in Mathematics, Henry Ernest Dudeney Question 283

-

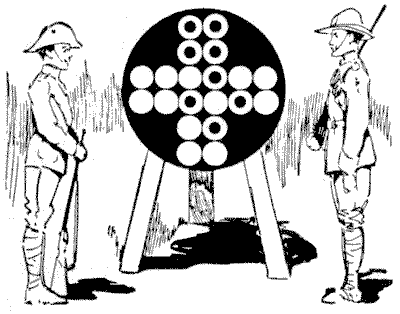

THE CROSS TARGET

In the illustration we have a somewhat curious target designed by an eccentric sharpshooter. His idea was that in order to score you must hit four circles in as many shots so that those four shots shall form a square. It will be seen by the results recorded on the target that two attempts have been successful. The first man hit the four circles at the top of the cross, and thus formed his square. The second man intended to hit the four in the bottom arm, but his second shot, on the left, went too high. This compelled him to complete his four in a different way than he intended. It will thus be seen that though it is immaterial which circle you hit at the first shot, the second shot may commit you to a definite procedure if you are to get your square. Now, the puzzle is to say in just how many different ways it is possible to form a square on the target with four shots.

Sources:Topics:Geometry Combinatorics -> Case Analysis / Checking Cases -> Processes / Procedures Combinatorics -> Combinatorial Geometry -> Grid Paper Geometry / Lattice Geometry

In the illustration we have a somewhat curious target designed by an eccentric sharpshooter. His idea was that in order to score you must hit four circles in as many shots so that those four shots shall form a square. It will be seen by the results recorded on the target that two attempts have been successful. The first man hit the four circles at the top of the cross, and thus formed his square. The second man intended to hit the four in the bottom arm, but his second shot, on the left, went too high. This compelled him to complete his four in a different way than he intended. It will thus be seen that though it is immaterial which circle you hit at the first shot, the second shot may commit you to a definite procedure if you are to get your square. Now, the puzzle is to say in just how many different ways it is possible to form a square on the target with four shots.

Sources:Topics:Geometry Combinatorics -> Case Analysis / Checking Cases -> Processes / Procedures Combinatorics -> Combinatorial Geometry -> Grid Paper Geometry / Lattice Geometry- Amusements in Mathematics, Henry Ernest Dudeney Question 284