Amusements in Mathematics, Henry Ernest Dudeney

-

Question 111 - REAPING THE CORN

A farmer had a square cornfield. The corn was all ripe for reaping, and, as he was short of men, it was arranged that he and his son should share the work between them. The farmer first cut one rod wide all round the square, thus leaving a smaller square of standing corn in the middle of the field. "Now," he said to his son, "I have cut my half of the field, and you can do your share." The son was not quite satisfied as to the proposed division of labour, and as the village schoolmaster happened to be passing, he appealed to that person to decide the matter. He found the farmer was quite correct, provided there was no dispute as to the size of the field, and on this point they were agreed. Can you tell the area of the field, as that ingenious schoolmaster succeeded in doing? -

Question 112 - A PUZZLING LEGACY

A man left a hundred acres of land to be divided among his three sons—Alfred, Benjamin, and Charles—in the proportion of one-third, one-fourth, and one-fifth respectively. But Charles died. How was the land to be divided fairly between Alfred and Benjamin? -

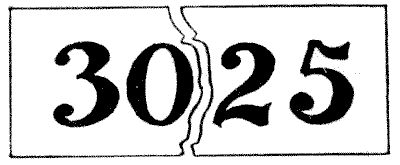

Question 113 - THE TORN NUMBER

I had the other day in my possession a label bearing the number `3\ 0\ 2\ 5` in large figures. This got accidentally torn in half, so that `30` was on one piece and `25` on the other, as shown on the illustration. On looking at these pieces I began to make a calculation, scarcely conscious of what I was doing, when I discovered this little peculiarity. If we add the `30` and the `25` together and square the sum we get as the result the complete original number on the label! Thus, `30` added to `25` is `55`, and `55` multiplied by `55` is `3025`. Curious, is it not? Now, the puzzle is to find another number, composed of four figures, all different, which may be divided in the middle and produce the same result.

-

Question 114 - CURIOUS NUMBERS

The number `48` has this peculiarity, that if you add `1` to it the result is a square number (`49`, the square of `7`), and if you add `1` to its half, you also get a square number (`25`, the square of `5`). Now, there is no limit to the numbers that have this peculiarity, and it is an interesting puzzle to find three more of them—the smallest possible numbers. What are they? -

Question 115 - A PRINTER'S ERROR

In a certain article a printer had to set up the figures `5^4xx2^3`, which, of course, means that the fourth power of `5` (`625`) is to be multiplied by the cube of `2` (`8`), the product of which is `5,000`. But he printed `5^4xx2^3` as `5\ 4\ 2\ 3`, which is not correct. Can you place four digits in the manner shown, so that it will be equally correct if the printer sets it up aright or makes the same blunder?

-

Question 116 - THE CONVERTED MISER

Mr. Jasper Bullyon was one of the very few misers who have ever been converted to a sense of their duty towards their less fortunate fellow-men. One eventful night he counted out his accumulated wealth, and resolved to distribute it amongst the deserving poor.

He found that if he gave away the same number of pounds every day in the year, he could exactly spread it over a twelvemonth without there being anything left over; but if he rested on the Sundays, and only gave away a fixed number of pounds every weekday, there would be one sovereign left over on New Year's Eve. Now, putting it at the lowest possible, what was the exact number of pounds that he had to distribute?

Could any question be simpler? A sum of pounds divided by one number of days leaves no remainder, but divided by another number of days leaves a sovereign over. That is all; and yet, when you come to tackle this little question, you will be surprised that it can become so puzzling.

-

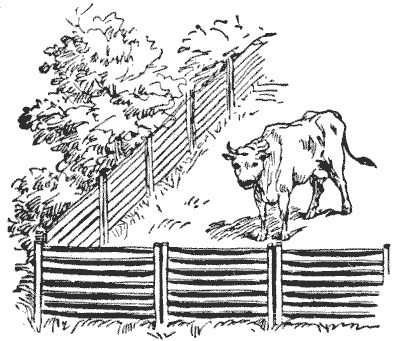

Question 117 - A FENCE PROBLEM

The practical usefulness of puzzles is a point that we are liable to overlook. Yet, as a matter of fact, I have from time to time received quite a large number of letters from individuals who have found that the mastering of some little principle upon which a puzzle was built has proved of considerable value to them in a most unexpected way. Indeed, it may be accepted as a good maxim that a puzzle is of little real value unless, as well as being amusing and perplexing, it conceals some instructive and possibly useful feature. It is, however, very curious how these little bits of acquired knowledge dovetail into the occasional requirements of everyday life, and equally curious to what strange and mysterious uses some of our readers seem to apply them. What, for example, can be the object of Mr. Wm. Oxley, who writes to me all the way from Iowa, in wishing to ascertain the dimensions of a field that he proposes to enclose, containing just as many acres as there shall be rails in the fence? The man wishes to fence in a perfectly square field which is to contain just as many acres as there are rails in the required fence. Each hurdle, or portion of fence, is seven rails high, and two lengths would extend one pole (`16`½ ft.): that is to say, there are fourteen rails to the pole, lineal measure. Now, what must be the size of the field?

The man wishes to fence in a perfectly square field which is to contain just as many acres as there are rails in the required fence. Each hurdle, or portion of fence, is seven rails high, and two lengths would extend one pole (`16`½ ft.): that is to say, there are fourteen rails to the pole, lineal measure. Now, what must be the size of the field?

-

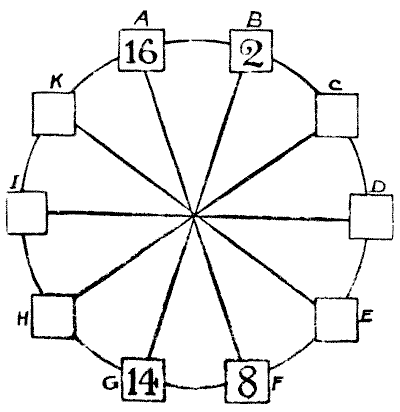

Question 118 - CIRCLING THE SQUARES

The puzzle is to place a different number in each of the ten squares so that the sum of the squares of any two adjacent numbers shall be equal to the sum of the squares of the two numbers diametrically opposite to them. The four numbers placed, as examples, must stand as they are. The square of `16` is `256`, and the square of `2` is `4`. Add these together, and the result is `260`. Also—the square of `14` is `196`, and the square of `8` is `64`. These together also make `260`. Now, in precisely the same way, B and C should be equal to G and H (the sum will not necessarily be `260`), A and K to F and E, H and I to C and D, and so on, with any two adjoining squares in the circle.

All you have to do is to fill in the remaining six numbers. Fractions are not allowed, and I shall show that no number need contain more than two figures.

-

Question 119 - RACKBRANE'S LITTLE LOSS

Professor Rackbrane was spending an evening with his old friends, Mr. and Mrs. Potts, and they engaged in some game (he does not say what game) of cards. The professor lost the first game, which resulted in doubling the money that both Mr. and Mrs. Potts had laid on the table. The second game was lost by Mrs. Potts, which doubled the money then held by her husband and the professor. Curiously enough, the third game was lost by Mr. Potts, and had the effect of doubling the money then held by his wife and the professor. It was then found that each person had exactly the same money, but the professor had lost five shillings in the course of play. Now, the professor asks, what was the sum of money with which he sat down at the table? Can you tell him? -

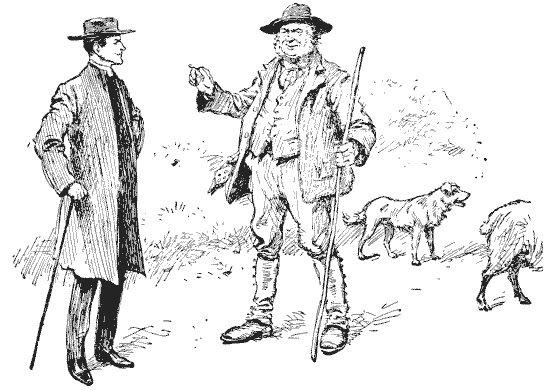

Question 120 - THE FARMER AND HIS SHEEP

Farmer Longmore had a curious aptitude for arithmetic, and was known in his district as the "mathematical farmer." The new vicar was not aware of this fact when, meeting his worthy parishioner one day in the lane, he asked him in the course of a short conversation, "Now, how many sheep have you altogether?" He was therefore rather surprised at Longmore's answer, which was as follows: "You can divide my sheep into two different parts, so that the difference between the two numbers is the same as the difference between their squares. Maybe, Mr. Parson, you will like to work out the little sum for yourself."

Can the reader say just how many sheep the farmer had? Supposing he had possessed only twenty sheep, and he divided them into the two parts `12` and `8`. Now, the difference between their squares, `144` and `64`, is `80`. So that will not do, for `4` and `80` are certainly not the same. If you can find numbers that work out correctly, you will know exactly how many sheep Farmer Longmore owned.