Amusements in Mathematics, Henry Ernest Dudeney

-

Question 141 - SATURDAY MARKETING

Here is an amusing little case of marketing which, although it deals with a good many items of money, leads up to a question of a totally different character. Four married couples went into their village on a recent Saturday night to do a little marketing. They had to be very economical, for among them they only possessed forty shilling coins. The fact is, Ann spent `1`s., Mary spent `2`s., Jane spent `3`s., and Kate spent `4`s. The men were rather more extravagant than their wives, for Ned Smith spent as much as his wife, Tom Brown twice as much as his wife, Bill Jones three times as much as his wife, and Jack Robinson four times as much as his wife. On the way home somebody suggested that they should divide what coin they had left equally among them. This was done, and the puzzling question is simply this: What was the surname of each woman? Can you pair off the four couples?

-

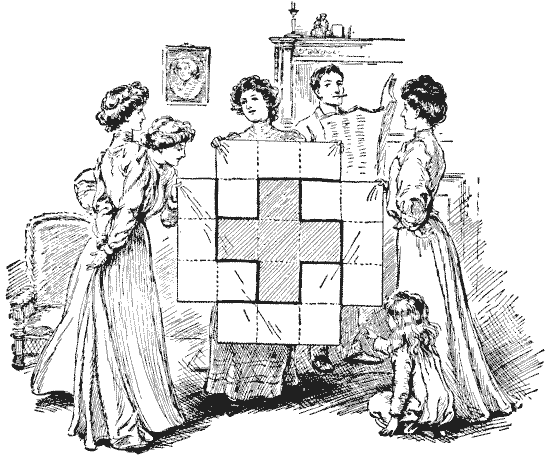

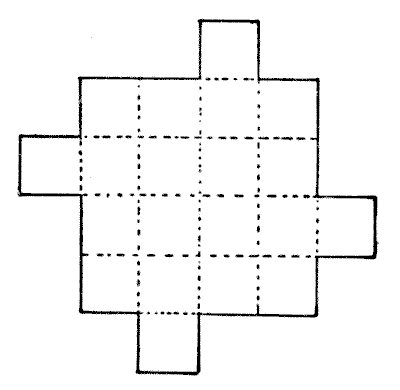

Question 142 - THE SILK PATCHWORK

The lady members of the Wilkinson family had made a simple patchwork quilt, as a small Christmas present, all composed of square pieces of the same size, as shown in the illustration. It only lacked the four corner pieces to make it complete. Somebody pointed out to them that if you unpicked the Greek cross in the middle and then cut the stitches along the dark joins, the four pieces all of the same size and shape would fit together and form a square. This the reader knows, from the solution in Fig. `39`, is quite easily done. But George Wilkinson suddenly suggested to them this poser. He said, "Instead of picking out the cross entire, and forming the square from four equal pieces, can you cut out a square entire and four equal pieces that will form a perfect Greek cross?" The puzzle is, of course, now quite easy.

-

Question 143 - TWO CROSSES FROM ONE

Cut a Greek cross into five pieces that will form two such crosses, both of the same size. The solution of this puzzle is very beautiful. -

Question 144 - THE CROSS AND THE TRIANGLE

Cut a Greek cross into six pieces that will form an equilateral triangle. This is another hard problem, and I will state here that a solution is practically impossible without a previous knowledge of my method of transforming an equilateral triangle into a square (see No. `26`, "Canterbury Puzzles"). -

Question 145 - THE FOLDED CROSS

Cut out of paper a Greek cross; then so fold it that with a single straight cut of the scissors the four pieces produced will form a square.

-

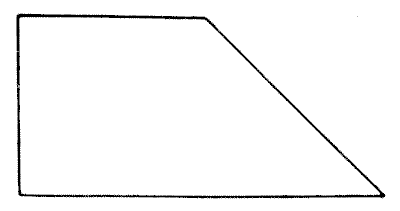

Question 146 - AN EASY DISSECTION PUZZLE

First, cut out a piece of paper or cardboard of the shape shown in the illustration. It will be seen at once that the proportions are simply those of a square attached to half of another similar square, divided diagonally. The puzzle is to cut it into four pieces all of precisely the same size and shape.

-

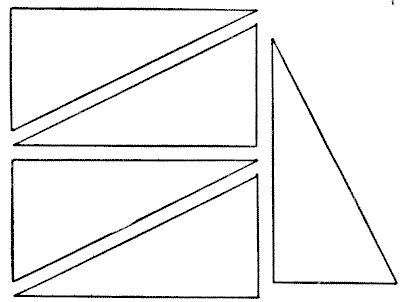

Question 147 - AN EASY SQUARE PUZZLE

If you take a rectangular piece of cardboard, twice as long as it is broad, and cut it in half diagonally, you will get two of the pieces shown in the illustration. The puzzle is with five such pieces of equal size to form a square. One of the pieces may be cut in two, but the others must be used intact.

-

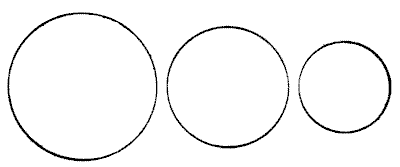

Question 148 - THE BUN PUZZLE

The three circles represent three buns, and it is simply required to show how these may be equally divided among four boys. The buns must be regarded as of equal thickness throughout and of equal thickness to each other. Of course, they must be cut into as few pieces as possible. To simplify it I will state the rather surprising fact that only five pieces are necessary, from which it will be seen that one boy gets his share in two pieces and the other three receive theirs in a single piece. I am aware that this statement "gives away" the puzzle, but it should not destroy its interest to those who like to discover the "reason why."

The three circles represent three buns, and it is simply required to show how these may be equally divided among four boys. The buns must be regarded as of equal thickness throughout and of equal thickness to each other. Of course, they must be cut into as few pieces as possible. To simplify it I will state the rather surprising fact that only five pieces are necessary, from which it will be seen that one boy gets his share in two pieces and the other three receive theirs in a single piece. I am aware that this statement "gives away" the puzzle, but it should not destroy its interest to those who like to discover the "reason why."

-

Question 149 - THE CHOCOLATE SQUARES

Here is a slab of chocolate, indented at the dotted lines so that the twenty squares can be easily separated. Make a copy of the slab in paper or cardboard and then try to cut it into nine pieces so that they will form four perfect squares all of exactly the same size.

Here is a slab of chocolate, indented at the dotted lines so that the twenty squares can be easily separated. Make a copy of the slab in paper or cardboard and then try to cut it into nine pieces so that they will form four perfect squares all of exactly the same size.

-

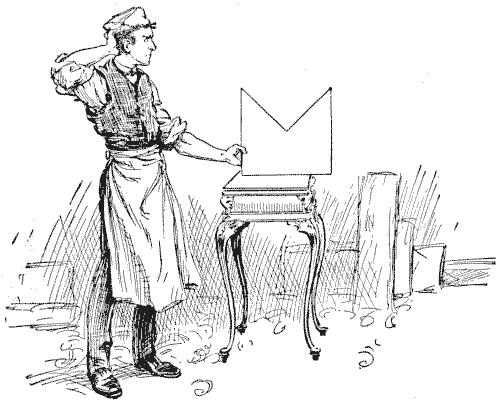

Question 150 - DISSECTING A MITRE

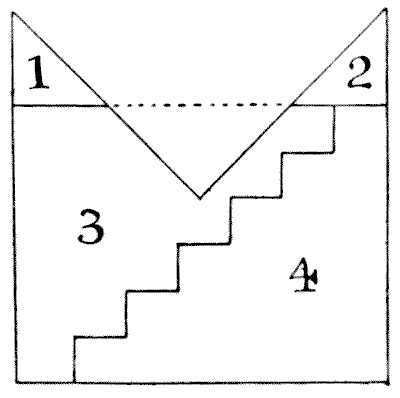

The figure that is perplexing the carpenter in the illustration represents a mitre. It will be seen that its proportions are those of a square with one quarter removed. The puzzle is to cut it into five pieces that will fit together and form a perfect square. I show an attempt, published in America, to perform the feat in four pieces, based on what is known as the "step principle," but it is a fallacy.

We are told first to cut oft the pieces `1` and `2` and pack them into the triangular space marked off by the dotted line, and so form a rectangle.

So far, so good. Now, we are directed to apply the old step principle, as shown, and, by moving down the piece `4` one step, form the required square. But, unfortunately, it does not produce a square: only an oblong. Call the three long sides of the mitre `84` in. each. Then, before cutting the steps, our rectangle in three pieces will be `84`×`63`. The steps must be `10`½ in. in height and `12` in. in breadth. Therefore, by moving down a step we reduce by `12` in. the side `84` in. and increase by `10`½ in. the side `63` in. Hence our final rectangle must be `72` in. × `73`½ in., which certainly is not a square! The fact is, the step principle can only be applied to rectangles with sides of particular relative lengths. For example, if the shorter side in this case were `61` `5/7` (instead of `63`), then the step method would apply. For the steps would then be `10` `2/7` in. in height and `12` in. in breadth. Note that `61` `5/7` × `84`= the square of `72`. At present no solution has been found in four pieces, and I do not believe one possible.