Amusements in Mathematics, Henry Ernest Dudeney

-

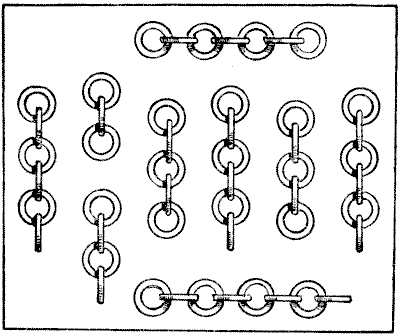

Question 421 - A CHAIN PUZZLE

This is a puzzle based on a pretty little idea first dealt with by the late Mr. Sam Loyd. A man had nine pieces of chain, as shown in the illustration. He wanted to join these fifty links into one endless chain. It will cost a penny to open any link and twopence to weld a link together again, but he could buy a new endless chain of the same character and quality for `2`s. `2`d. What was the cheapest course for him to adopt? Unless the reader is cunning he may find himself a good way out in his answer.

This is a puzzle based on a pretty little idea first dealt with by the late Mr. Sam Loyd. A man had nine pieces of chain, as shown in the illustration. He wanted to join these fifty links into one endless chain. It will cost a penny to open any link and twopence to weld a link together again, but he could buy a new endless chain of the same character and quality for `2`s. `2`d. What was the cheapest course for him to adopt? Unless the reader is cunning he may find himself a good way out in his answer.

-

Question 422 - THE SABBATH PUZZLE

I have come across the following little poser in an old book. I wonder how many readers will see the author's intended solution to the riddle.

Christians the week's first day for Sabbath hold;

The Jews the seventh, as they did of old;

The Turks the sixth, as we have oft been told.

How can these three, in the same place and day,

Have each his own true Sabbath? tell, I pray. -

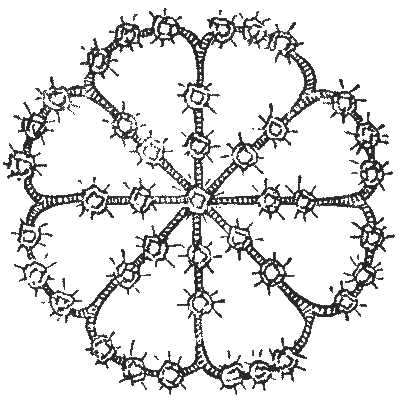

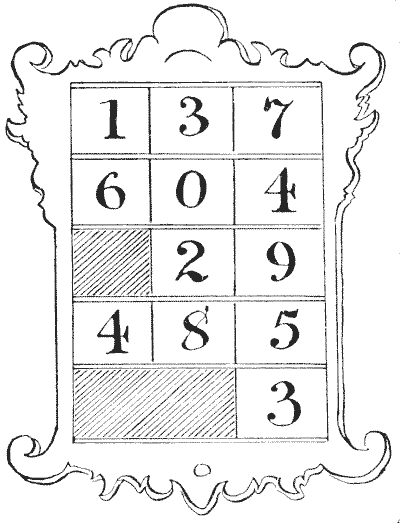

Question 423 - THE RUBY BROOCH

The annals of Scotland Yard contain some remarkable cases of jewel robberies, but one of the most perplexing was the theft of Lady Littlewood's rubies. There have, of course, been many greater robberies in point of value, but few so artfully conceived. Lady Littlewood, of Romley Manor, had a beautiful but rather eccentric heirloom in the form of a ruby brooch. While staying at her town house early in the eighties she took the jewel to a shop in Brompton for some slight repairs.

"A fine collection of rubies, madam," said the shopkeeper, to whom her ladyship was a stranger.

"Yes," she replied; "but curiously enough I have never actually counted them. My mother once pointed out to me that if you start from the centre and count up one line, along the outside and down the next line, there are always eight rubies. So I should always know if a stone were missing."

Six months later a brother of Lady Littlewood's, who had returned from his regiment in India, noticed that his sister was wearing the ruby brooch one night at a county ball, and on their return home asked to look at it more closely. He immediately detected the fact that four of the stones were gone.

"How can that possibly be?" said Lady Littlewood. "If you count up one line from the centre, along the edge, and down the next line, in any direction, there are always eight stones. This was always so and is so now. How, therefore, would it be possible to remove a stone without my detecting it?"

"Nothing could be simpler," replied the brother. "I know the brooch well. It originally contained forty-five stones, and there are now only forty-one. Somebody has stolen four rubies, and then reset as small a number of the others as possible in such a way that there shall always be eight in any of the directions you have mentioned."

There was not the slightest doubt that the Brompton jeweller was the thief, and the matter was placed in the hands of the police. But the man was wanted for other robberies, and had left the neighbourhood some time before. To this day he has never been found.

The interesting little point that at first baffled the police, and which forms the subject of our puzzle, is this: How were the forty-five rubies originally arranged on the brooch? The illustration shows exactly how the forty-one were arranged after it came back from the jeweller; but although they count eight correctly in any of the directions mentioned, there are four stones missing.

-

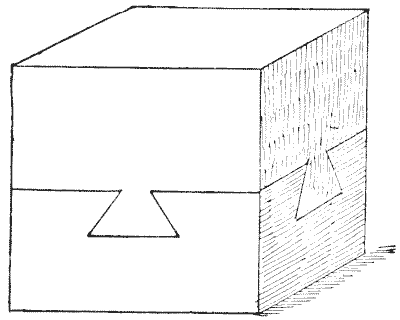

Question 424 - THE DOVETAILED BLOCK

Here is a curious mechanical puzzle that was given to me some years ago, but I cannot say who first invented it. It consists of two solid blocks of wood securely dovetailed together. On the other two vertical sides that are not visible the appearance is precisely the same as on those shown. How were the pieces put together? When I published this little puzzle in a London newspaper I received (though they were unsolicited) quite a stack of models, in oak, in teak, in mahogany, rosewood, satinwood, elm, and deal; some half a foot in length, and others varying in size right down to a delicate little model about half an inch square. It seemed to create considerable interest.

Topics:Geometry -> Solid Geometry / Geometry in Space

Here is a curious mechanical puzzle that was given to me some years ago, but I cannot say who first invented it. It consists of two solid blocks of wood securely dovetailed together. On the other two vertical sides that are not visible the appearance is precisely the same as on those shown. How were the pieces put together? When I published this little puzzle in a London newspaper I received (though they were unsolicited) quite a stack of models, in oak, in teak, in mahogany, rosewood, satinwood, elm, and deal; some half a foot in length, and others varying in size right down to a delicate little model about half an inch square. It seemed to create considerable interest.

Topics:Geometry -> Solid Geometry / Geometry in Space -

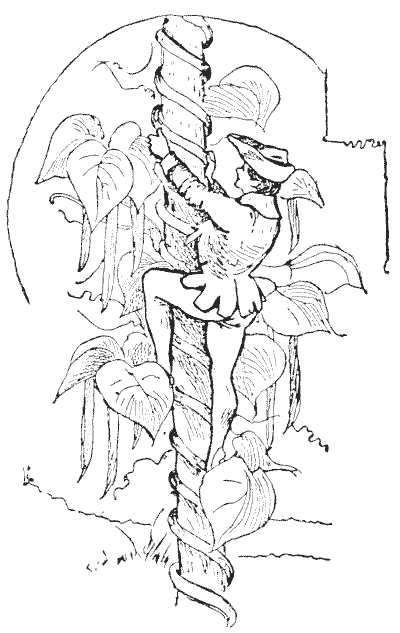

Question 425 - JACK AND THE BEANSTALK

The illustration, by a British artist, is a sketch of Jack climbing the beanstalk. Now, the artist has made a serious blunder in this drawing. Can you find out what it is?

The illustration, by a British artist, is a sketch of Jack climbing the beanstalk. Now, the artist has made a serious blunder in this drawing. Can you find out what it is?

-

Question 426 - THE HYMN-BOARD POSER

The worthy vicar of Chumpley St. Winifred is in great distress. A little church difficulty has arisen that all the combined intelligence of the parish seems unable to surmount. What this difficulty is I will state hereafter, but it may add to the interest of the problem if I first give a short account of the curious position that has been brought about. It all has to do with the church hymn-boards, the plates of which have become so damaged that they have ceased to fulfil the purpose for which they were devised. A generous parishioner has promised to pay for a new set of plates at a certain rate of cost; but strange as it may seem, no agreement can be come to as to what that cost should be. The proposed maker of the plates has named a price which the donor declares to be absurd. The good vicar thinks they are both wrong, so he asks the schoolmaster to work out the little sum. But this individual declares that he can find no rule bearing on the subject in any of his arithmetic books. An application having been made to the local medical practitioner, as a man of more than average intellect at Chumpley, he has assured the vicar that his practice is so heavy that he has not had time even to look at it, though his assistant whispers that the doctor has been sitting up unusually late for several nights past. Widow Wilson has a smart son, who is reputed to have once won a prize for puzzle-solving. He asserts that as he cannot find any solution to the problem it must have something to do with the squaring of the circle, the duplication of the cube, or the trisection of an angle; at any rate, he has never before seen a puzzle on the principle, and he gives it up.

This was the state of affairs when the assistant curate (who, I should say, had frankly confessed from the first that a profound study of theology had knocked out of his head all the knowledge of mathematics he ever possessed) kindly sent me the puzzle.

A church has three hymn-boards, each to indicate the numbers of five different hymns to be sung at a service. All the boards are in use at the same service. The hymn-book contains `700` hymns. A new set of numbers is required, and a kind parishioner offers to present a set painted on metal plates, but stipulates that only the smallest number of plates necessary shall be purchased. The cost of each plate is to be `6`d., and for the painting of each plate the charges are to be: For one plate, `1`s.; for two plates alike, `11`¾d. each; for three plates alike, `11`½d. each, and so on, the charge being one farthing less per plate for each similarly painted plate. Now, what should be the lowest cost?

Readers will note that they are required to use every legitimate and practical method of economy. The illustration will make clear the nature of the three hymn-boards and plates. The five hymns are here indicated by means of twelve plates. These plates slide in separately at the back, and in the illustration there is room, of course, for three more plates.

-

Question 427 - PHEASANT-SHOOTING

A Cockney friend, who is very apt to draw the long bow, and is evidently less of a sportsman than he pretends to be, relates to me the following not very credible yarn:—

"I've just been pheasant-shooting with my friend the duke. We had splendid sport, and I made some wonderful shots. What do you think of this, for instance? Perhaps you can twist it into a puzzle. The duke and I were crossing a field when suddenly twenty-four pheasants rose on the wing right in front of us. I fired, and two-thirds of them dropped dead at my feet. Then the duke had a shot at what were left, and brought down three-twenty-fourths of them, wounded in the wing. Now, out of those twenty-four birds, how many still remained?"

It seems a simple enough question, but can the reader give a correct answer?

-

Question 428 - THE GARDENER AND THE COOK

A correspondent, signing himself "Simple Simon," suggested that I should give a special catch puzzle in the issue of The Weekly Dispatch for All Fools' Day, `1900`. So I gave the following, and it caused considerable amusement; for out of a very large body of competitors, many quite expert, not a single person solved it, though it ran for nearly a month.

"The illustration is a fancy sketch of my correspondent, 'Simple Simon,' in the act of trying to solve the following innocent little arithmetical puzzle. A race between a man and a woman that I happened to witness one All Fools' Day has fixed itself indelibly on my memory. It happened at a country-house, where the gardener and the cook decided to run a race to a point `100` feet straight away and return. I found that the gardener ran `3` feet at every bound and the cook only `2` feet, but then she made three bounds to his two. Now, what was the result of the race?"

A fortnight after publication I added the following note: "It has been suggested that perhaps there is a catch in the 'return,' but there is not. The race is to a point `100` feet away and home again—that is, a distance of `200` feet. One correspondent asks whether they take exactly the same time in turning, to which I reply that they do. Another seems to suspect that it is really a conundrum, and that the answer is that 'the result of the race was a (matrimonial) tie.' But I had no such intention. The puzzle is an arithmetical one, as it purports to be."

-

Question 429 - PLACING HALFPENNIES

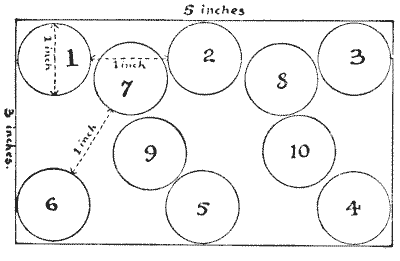

Here is an interesting little puzzle suggested to me by Mr. W. T. Whyte. Mark off on a sheet of paper a rectangular space `5` inches by `3` inches, and then find the greatest number of halfpennies that can be placed within the enclosure under the following conditions. A halfpenny is exactly an inch in diameter. Place your first halfpenny where you like, then place your second coin at exactly the distance of an inch from the first, the third an inch distance from the second, and so on. No halfpenny may touch another halfpenny or cross the boundary. Our illustration will make the matter perfectly clear. No. `2` coin is an inch from No. `1`; No. `3` an inch from No. `2`; No. `4` an inch from No. `3`; but after No. `10` is placed we can go no further in this attempt. Yet several more halfpennies might have been got in. How many can the reader place?

Here is an interesting little puzzle suggested to me by Mr. W. T. Whyte. Mark off on a sheet of paper a rectangular space `5` inches by `3` inches, and then find the greatest number of halfpennies that can be placed within the enclosure under the following conditions. A halfpenny is exactly an inch in diameter. Place your first halfpenny where you like, then place your second coin at exactly the distance of an inch from the first, the third an inch distance from the second, and so on. No halfpenny may touch another halfpenny or cross the boundary. Our illustration will make the matter perfectly clear. No. `2` coin is an inch from No. `1`; No. `3` an inch from No. `2`; No. `4` an inch from No. `3`; but after No. `10` is placed we can go no further in this attempt. Yet several more halfpennies might have been got in. How many can the reader place?

-

Question 430 - FIND THE MAN'S WIFE

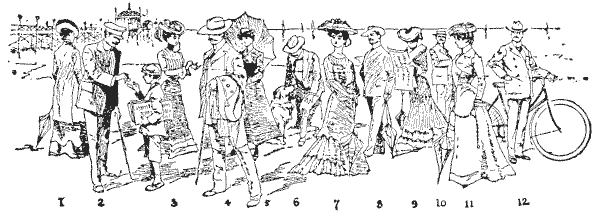

One summer day in `1903` I was loitering on the Brighton front, watching the people strolling about on the beach, when the friend who was with me suddenly drew my attention to an individual who was standing alone, and said, "Can you point out that man's wife? They are stopping at the same hotel as I am, and the lady is one of those in view." After a few minutes' observation, I was successful in indicating the lady correctly. My friend was curious to know by what method of reasoning I had arrived at the result. This was my answer:—

"We may at once exclude that Sister of Mercy and the girl in the short frock; also the woman selling oranges. It cannot be the lady in widows' weeds. It is not the lady in the bath chair, because she is not staying at your hotel, for I happened to see her come out of a private house this morning assisted by her maid. The two ladies in red breakfasted at my hotel this morning, and as they were not wearing outdoor dress I conclude they are staying there. It therefore rests between the lady in blue and the one with the green parasol. But the left hand that holds the parasol is, you see, ungloved and bears no wedding-ring. Consequently I am driven to the conclusion that the lady in blue is the man's wife—and you say this is correct."

Now, as my friend was an artist, and as I thought an amusing puzzle might be devised on the lines of his question, I asked him to make me a drawing according to some directions that I gave him, and I have pleasure in presenting his production to my readers. It will be seen that the picture shows six men and six ladies: Nos. `1, 3, 5, 7, 9`, and `11` are ladies, and Nos. `2, 4, 6, 8, 10`, and `12` are men. These twelve individuals represent six married couples, all strangers to one another, who, in walking aimlessly about, have got mixed up. But we are only concerned with the man that is wearing a straw hat—Number `10`. The puzzle is to find this man's wife. Examine the six ladies carefully, and see if you can determine which one of them it is.

I showed the picture at the time to a few friends, and they expressed very different opinions on the matter. One said, "I don't believe he would marry a girl like Number `7`." Another said, "I am sure a nice girl like Number `3` would not marry such a fellow!" Another said, "It must be Number `1`, because she has got as far away as possible from the brute!" It was suggested, again, that it must be Number `11`, because "he seems to be looking towards her;" but a cynic retorted, "For that very reason, if he is really looking at her, I should say that she is not his wife!"

I now leave the question in the hands of my readers. Which is really Number `10`'s wife?

The illustration is of necessity considerably reduced from the large scale on which it originally appeared in The Weekly Dispatch (24th May `1903`), but it is hoped that the details will be sufficiently clear to allow the reader to derive entertainment from its examination. In any case the solution given will enable him to follow the points with interest.