Amusements in Mathematics, Henry Ernest Dudeney

-

Question 411 - A MAGIC SQUARE OF COMPOSITES

As we have just discussed the construction of magic squares with prime numbers, the following forms an interesting companion problem. Make a magic square with nine consecutive composite numbers—the smallest possible.Topics:Number Theory -> Prime Numbers -

Question 412 - THE MAGIC KNIGHT'S TOUR

Here is a problem that has never yet been solved, nor has its impossibility been demonstrated. Play the knight once to every square of the chessboard in a complete tour, numbering the squares in the order visited, so that when completed the square shall be "magic," adding up to `260` in every column, every row, and each of the two long diagonals. I shall give the best answer that I have been able to obtain, in which there is a slight error in the diagonals alone. Can a perfect solution be found? I am convinced that it cannot, but it is only a "pious opinion."

-

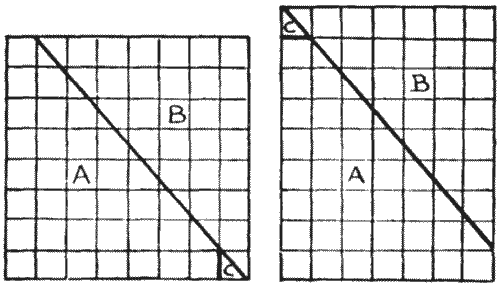

Question 413 - A CHESSBOARD FALLACY

"Here is a diagram of a chessboard," he said. "You see there are sixty-four squares—eight by eight. Now I draw a straight line from the top left-hand corner, where the first and second squares meet, to the bottom right-hand corner. I cut along this line with the scissors, slide up the piece that I have marked B, and then clip off the little corner C by a cut along the first upright line. This little piece will exactly fit into its place at the top, and we now have an oblong with seven squares on one side and nine squares on the other. There are, therefore, now only sixty-three squares, because seven multiplied by nine makes sixty-three. Where on earth does that lost square go to? I have tried over and over again to catch the little beggar, but he always eludes me. For the life of me I cannot discover where he hides himself."

"It seems to be like the other old chessboard fallacy, and perhaps the explanation is the same," said Reginald—"that the pieces do not exactly fit."

"But they do fit," said Uncle John. "Try it, and you will see."

Later in the evening Reginald and George, were seen in a corner with their heads together, trying to catch that elusive little square, and it is only fair to record that before they retired for the night they succeeded in securing their prey, though some others of the company failed to see it when captured. Can the reader solve the little mystery?

-

Question 414 - WHO WAS FIRST?

Anderson, Biggs, and Carpenter were staying together at a place by the seaside. One day they went out in a boat and were a mile at sea when a rifle was fired on shore in their direction. Why or by whom the shot was fired fortunately does not concern us, as no information on these points is obtainable, but from the facts I picked up we can get material for a curious little puzzle for the novice.

It seems that Anderson only heard the report of the gun, Biggs only saw the smoke, and Carpenter merely saw the bullet strike the water near them. Now, the question arises: Which of them first knew of the discharge of the rifle?

Topics:Logic -> Reasoning / Logic -

Question 415 - A WONDERFUL VILLAGE

There is a certain village in Japan, situated in a very low valley, and yet the sun is nearer to the inhabitants every noon, by `3,000` miles and upwards, than when he either rises or sets to these people. In what part of the country is the village situated? -

Question 416 - A CALENDAR PUZZLE

If the end of the world should come on the first day of a new century, can you say what are the chances that it will happen on a Sunday? -

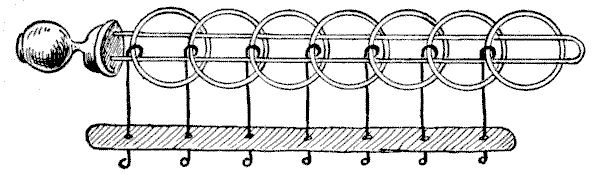

Question 417 - THE TIRING IRONS

The illustration represents one of the most ancient of all mechanical puzzles. Its origin is unknown. Cardan, the mathematician, wrote about it in `1550`, and Wallis in `1693`; while it is said still to be found in obscure English villages (sometimes deposited in strange places, such as a church belfry), made of iron, and appropriately called "tiring-irons," and to be used by the Norwegians to-day as a lock for boxes and bags. In the toyshops it is sometimes called the "Chinese rings," though there seems to be no authority for the description, and it more frequently goes by the unsatisfactory name of "the puzzling rings." The French call it "Baguenaudier."

The puzzle will be seen to consist of a simple loop of wire fixed in a handle to be held in the left hand, and a certain number of rings secured by wires which pass through holes in the bar and are kept there by their blunted ends. The wires work freely in the bar, but cannot come apart from it, nor can the wires be removed from the rings. The general puzzle is to detach the loop completely from all the rings, and then to put them all on again.

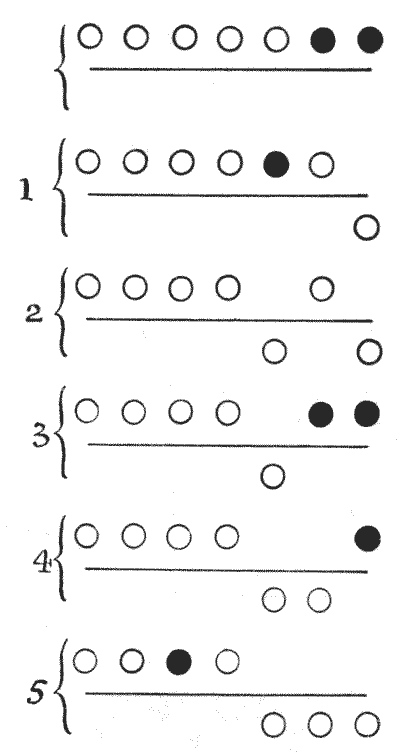

Now, it will be seen at a glance that the first ring (to the right) can be taken off at any time by sliding it over the end and dropping it through the loop; or it may be put on by reversing the operation. With this exception, the only ring that can ever be removed is the one that happens to be a contiguous second on the loop at the right-hand end. Thus, with all the rings on, the second can be dropped at once; with the first ring down, you cannot drop the second, but may remove the third; with the first three rings down, you cannot drop the fourth, but may remove the fifth; and so on. It will be found that the first and second rings can be dropped together or put on together; but to prevent confusion we will throughout disallow this exceptional double move, and say that only one ring may be put on or removed at a time.

We can thus take off one ring in `1` move; two rings in `2` moves; three rings in `5` moves; four rings in `10` moves; five rings in `21` moves; and if we keep on doubling (and adding one where the number of rings is odd) we may easily ascertain the number of moves for completely removing any number of rings. To get off all the seven rings requires `85` moves. Let us look at the five moves made in removing the first three rings, the circles above the line standing for rings on the loop and those under for rings off the loop.

Drop the first ring; drop the third; put up the first; drop the second; and drop the first—`5` moves, as shown clearly in the diagrams. The dark circles show at each stage, from the starting position to the finish, which rings it is possible to drop. After move `2` it will be noticed that no ring can be dropped until one has been put on, because the first and second rings from the right now on the loop are not together. After the fifth move, if we wish to remove all seven rings we must now drop the fifth. But before we can then remove the fourth it is necessary to put on the first three and remove the first two. We shall then have `7, 6, 4, 3` on the loop, and may therefore drop the fourth. When we have put on `2` and `1` and removed `3, 2, 1`, we may drop the seventh ring. The next operation then will be to get `6, 5, 4, 3, 2, 1` on the loop and remove `4, 3, 2, 1`, when `6` will come off; then get `5, 4, 3, 2, 1` on the loop, and remove `3, 2, 1`, when `5` will come off; then get `4, 3, 2, 1` on the loop and remove `2, 1`, when `4` will come off; then get `3, 2, 1` on the loop and remove `1`, when `3` will come off; then get `2, 1` on the loop, when `2` will come off; and `1` will fall through on the 85th move, leaving the loop quite free. The reader should now be able to understand the puzzle, whether or not he has it in his hand in a practical form.

The particular problem I propose is simply this. Suppose there are altogether fourteen rings on the tiring-irons, and we proceed to take them all off in the correct way so as not to waste any moves. What will be the position of the rings after the `9`,999th move has been made?

-

Question 418 - SUCH A GETTING UPSTAIRS

In a suburban villa there is a small staircase with eight steps, not counting the landing. The little puzzle with which Tommy Smart perplexed his family is this. You are required to start from the bottom and land twice on the floor above (stopping there at the finish), having returned once to the ground floor. But you must be careful to use every tread the same number of times. In how few steps can you make the ascent? It seems a very simple matter, but it is more than likely that at your first attempt you will make a great many more steps than are necessary. Of course you must not go more than one riser at a time.

Tommy knows the trick, and has shown it to his father, who professes to have a contempt for such things; but when the children are in bed the pater will often take friends out into the hall and enjoy a good laugh at their bewilderment. And yet it is all so very simple when you know how it is done.

-

Question 419 - THE FIVE PENNIES

Here is a really hard puzzle, and yet its conditions are so absurdly simple. Every reader knows how to place four pennies so that they are equidistant from each other. All you have to do is to arrange three of them flat on the table so that they touch one another in the form of a triangle, and lay the fourth penny on top in the centre. Then, as every penny touches every other penny, they are all at equal distances from one another. Now try to do the same thing with five pennies—place them so that every penny shall touch every other penny—and you will find it a different matter altogether.Topics:Geometry -> Solid Geometry / Geometry in Space -

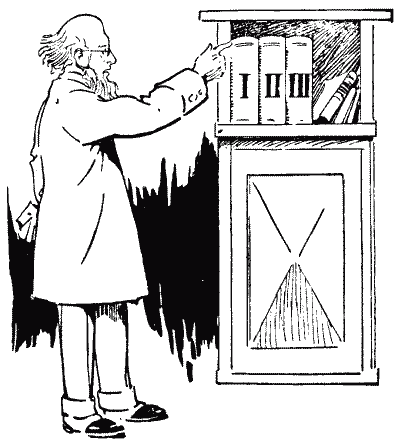

Question 420 - THE INDUSTRIOUS BOOKWORM

Our friend Professor Rackbrane is seen in the illustration to be propounding another of his little posers. He is explaining that since he last had occasion to take down those three volumes of a learned book from their place on his shelves a bookworm has actually bored a hole straight through from the first page to the last. He says that the leaves are together three inches thick in each volume, and that every cover is exactly one-eighth of an inch thick, and he asks how long a tunnel had the industrious worm to bore in preparing his new tube railway. Can you tell him?

Topics:Algebra -> Word Problems

Our friend Professor Rackbrane is seen in the illustration to be propounding another of his little posers. He is explaining that since he last had occasion to take down those three volumes of a learned book from their place on his shelves a bookworm has actually bored a hole straight through from the first page to the last. He says that the leaves are together three inches thick in each volume, and that every cover is exactly one-eighth of an inch thick, and he asks how long a tunnel had the industrious worm to bore in preparing his new tube railway. Can you tell him?

Topics:Algebra -> Word Problems