Amusements in Mathematics, Henry Ernest Dudeney

-

Question 91 - MORE MIXED FRACTIONS

When I first published my solution to the last puzzle, I was led to attempt the expression of all numbers in turn up to `100` by a mixed fraction containing all the nine digits. Here are twelve numbers for the reader to try his hand at: `13, 14, 15, 16, 18, 20, 27, 36, 40, 69, 72, 94`. Use every one of the nine digits once, and only once, in every case.

-

Question 92 - DIGITAL SQUARE NUMBERS

Here are the nine digits so arranged that they form four square numbers: `9, 81, 324, 576`. Now, can you put them all together so as to form a single square number—(I) the smallest possible, and (II) the largest possible? -

Question 93 - THE MYSTIC ELEVEN

Can you find the largest possible number containing any nine of the ten digits (calling nought a digit) that can be divided by `11` without a remainder? Can you also find the smallest possible number produced in the same way that is divisible by `11`? Here is an example, where the digit `5` has been omitted: `896743012`. This number contains nine of the digits and is divisible by `11`, but it is neither the largest nor the smallest number that will work.

-

Question 94 - THE DIGITAL CENTURY

`1\ 2\ 3\ 4\ 5\ 6\ 7\ 8\ 9 = 100`.

It is required to place arithmetical signs between the nine figures so that they shall equal `100`. Of course, you must not alter the present numerical arrangement of the figures. Can you give a correct solution that employs (`1`) the fewest possible signs, and (`2`) the fewest possible separate strokes or dots of the pen? That is, it is necessary to use as few signs as possible, and those signs should be of the simplest form. The signs of addition and multiplication (+ and ×) will thus count as two strokes, the sign of subtraction (-) as one stroke, the sign of division (÷) as three, and so on.

-

Question 95 - THE FOUR SEVENS

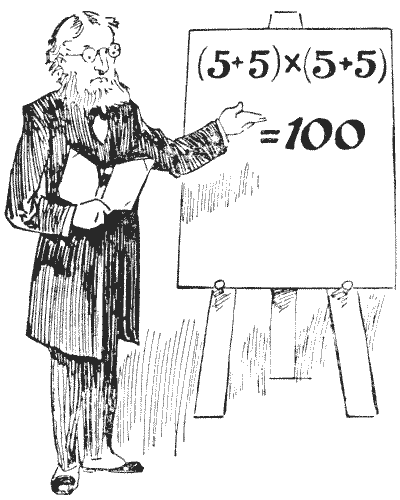

In the illustration Professor Rackbrane is seen demonstrating one of the little posers with which he is accustomed to entertain his class. He believes that by taking his pupils off the beaten tracks he is the better able to secure their attention, and to induce original and ingenious methods of thought. He has, it will be seen, just shown how four `5`'s may be written with simple arithmetical signs so as to represent `100`. Every juvenile reader will see at a glance that his example is quite correct. Now, what he wants you to do is this: Arrange four `7`'s (neither more nor less) with arithmetical signs so that they shall represent `100`. If he had said we were to use four `9`'s we might at once have written `99 9/9`, but the four `7`'s call for rather more ingenuity. Can you discover the little trick?

In the illustration Professor Rackbrane is seen demonstrating one of the little posers with which he is accustomed to entertain his class. He believes that by taking his pupils off the beaten tracks he is the better able to secure their attention, and to induce original and ingenious methods of thought. He has, it will be seen, just shown how four `5`'s may be written with simple arithmetical signs so as to represent `100`. Every juvenile reader will see at a glance that his example is quite correct. Now, what he wants you to do is this: Arrange four `7`'s (neither more nor less) with arithmetical signs so that they shall represent `100`. If he had said we were to use four `9`'s we might at once have written `99 9/9`, but the four `7`'s call for rather more ingenuity. Can you discover the little trick? -

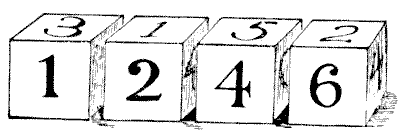

Question 96 - THE DICE NUMBERS

I have a set of four dice, not marked with spots in the ordinary way, but with Arabic figures, as shown in the illustration. Each die, of course, bears the numbers `1` to `6`. When put together they will form a good many, different numbers. As represented they make the number `1246`. Now, if I make all the different four-figure numbers that are possible with these dice (never putting the same figure more than once in any number), what will they all add up to? You are allowed to turn the `6` upside down, so as to represent a `9`. I do not ask, or expect, the reader to go to all the labour of writing out the full list of numbers and then adding them up. Life is not long enough for such wasted energy. Can you get at the answer in any other way?

-

Question 97 - THE SPOT ON THE TABLE

A boy, recently home from school, wished to give his father an exhibition of his precocity. He pushed a large circular table into the corner of the room, as shown in the illustration, so that it touched both walls, and he then pointed to a spot of ink on the extreme edge.

"Here is a little puzzle for you, pater," said the youth. "That spot is exactly eight inches from one wall and nine inches from the other. Can you tell me the diameter of the table without measuring it?"

The boy was overheard to tell a friend, "It fairly beat the guv'nor;" but his father is known to have remarked to a City acquaintance that he solved the thing in his head in a minute. I often wonder which spoke the truth.

Topics:Geometry -> Plane Geometry -> Circles Algebra -> Equations Algebra -> Word Problems Geometry -> Plane Geometry -> Pythagorean Theorem -

Question 98 - ACADEMIC COURTESIES

In a certain mixed school, where a special feature was made of the inculcation of good manners, they had a curious rule on assembling every morning. There were twice as many girls as boys. Every girl made a bow to every other girl, to every boy, and to the teacher. Every boy made a bow to every other boy, to every girl, and to the teacher. In all there were nine hundred bows made in that model academy every morning. Now, can you say exactly how many boys there were in the school? If you are not very careful, you are likely to get a good deal out in your calculation. -

Question 99 - THE THIRTY-THREE PEARLS

"A man I know," said Teddy Nicholson at a certain family party, "possesses a string of thirty-three pearls. The middle pearl is the largest and best of all, and the others are so selected and arranged that, starting from one end, each successive pearl is worth £`100` more than the preceding one, right up to the big pearl. From the other end the pearls increase in value by £`150` up to the large pearl. The whole string is worth £`65,000`. What is the value of that large pearl?"

"Pearls and other articles of clothing," said Uncle Walter, when the price of the precious gem had been discovered, "remind me of Adam and Eve. Authorities, you may not know, differ as to the number of apples that were eaten by Adam and Eve. It is the opinion of some that Eve `8` (ate) and Adam `2` (too), a total of `10` only. But certain mathematicians have figured it out differently, and hold that Eve `8` and Adam a total of `16`. Yet the most recent investigators think the above figures entirely wrong, for if Eve `8` and Adam `82`, the total must be `90`."

"Well," said Harry, "it seems to me that if there were giants in those days, probably Eve `81` and Adam `82`, which would give a total of `163`."

"I am not at all satisfied," said Maud. "It seems to me that if Eve `81` and Adam `812`, they together consumed `893`."

"I am sure you are all wrong," insisted Mr. Wilson, "for I consider that Eve `814` Adam, and Adam `8124` Eve, so we get a total of `8,938`."

"But, look here," broke in Herbert. "If Eve `814` Adam and Adam `81242` oblige Eve, surely the total must have been `82,056`!"

At this point Uncle Walter suggested that they might let the matter rest. He declared it to be clearly what mathematicians call an indeterminate problem.

Topics:Arithmetic Algebra -> Equations Algebra -> Word Problems Algebra -> Sequences -> Arithmetic Progression / Arithmetic Sequence -

Question 100 - THE LABOURER'S PUZZLE

Professor Rackbrane, during one of his rambles, chanced to come upon a man digging a deep hole.

"Good morning," he said. "How deep is that hole?"

"Guess," replied the labourer. "My height is exactly five feet ten inches."

"How much deeper are you going?" said the professor.

"I am going twice as deep," was the answer, "and then my head will be twice as far below ground as it is now above ground."

Rackbrane now asks if you could tell how deep that hole would be when finished.