Geometry, Solid Geometry / Geometry in Space

Solid Geometry, or Geometry in Space, focuses on three-dimensional shapes such as cubes, spheres, cylinders, cones, and polyhedra. Questions typically involve calculating their surface areas and volumes, understanding their properties, and visualizing relationships between them in 3D space.

Polyhedra-

THE CARDBOARD BOX

This puzzle is not difficult, but it will be found entertaining to discover the simple rule for its solution. I have a rectangular cardboard box. The top has an area of `120` square inches, the side `96` square inches, and the end `80` square inches. What are the exact dimensions of the box?Sources:Topics:Geometry -> Solid Geometry / Geometry in Space Geometry -> Area Calculation Algebra -> Equations Algebra -> Word Problems- Amusements in Mathematics, Henry Ernest Dudeney Question 178

-

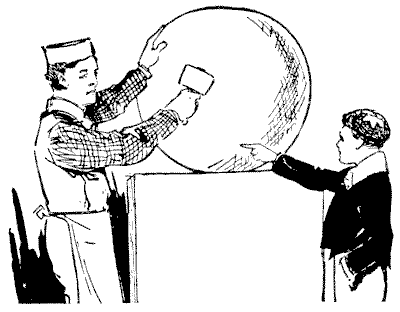

THE BALL PROBLEM

A stonemason was engaged the other day in cutting out a round ball for the purpose of some architectural decoration, when a smart schoolboy came upon the scene.

"Look here," said the mason, "you seem to be a sharp youngster, can you tell me this? If I placed this ball on the level ground, how many other balls of the same size could I lay around it (also on the ground) so that every ball should touch this one?"

The boy at once gave the correct answer, and then put this little question to the mason:—

"If the surface of that ball contained just as many square feet as its volume contained cubic feet, what would be the length of its diameter?"

The stonemason could not give an answer. Could you have replied correctly to the mason's and the boy's questions?

Sources:- Amusements in Mathematics, Henry Ernest Dudeney Question 188

-

A KITE-FLYING PUZZLE

While accompanying my friend Professor Highflite during a scientific kite-flying competition on the South Downs of Sussex I was led into a little calculation that ought to interest my readers. The Professor was paying out the wire to which his kite was attached from a winch on which it had been rolled into a perfectly spherical form. This ball of wire was just two feet in diameter, and the wire had a diameter of one-hundredth of an inch. What was the length of the wire?

Now, a simple little question like this that everybody can perfectly understand will puzzle many people to answer in any way. Let us see whether, without going into any profound mathematical calculations, we can get the answer roughly—say, within a mile of what is correct! We will assume that when the wire is all wound up the ball is perfectly solid throughout, and that no allowance has to be made for the axle that passes through it. With that simplification, I wonder how many readers can state within even a mile of the correct answer the length of that wire.

Sources:Topics:Geometry -> Solid Geometry / Geometry in Space Arithmetic Geometry -> Area Calculation Algebra -> Word Problems Units of Measurement- Amusements in Mathematics, Henry Ernest Dudeney Question 200

-

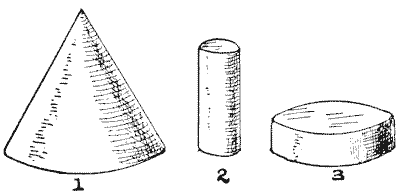

THE CONE PUZZLE

I have a wooden cone, as shown in Fig. `1`. How am I to cut out of it the greatest possible cylinder? It will be seen that I can cut out one that is long and slender, like Fig. `2`, or short and thick, like Fig. `3`. But neither is the largest possible. A child could tell you where to cut, if he knew the rule. Can you find this simple rule?

Sources:Topics:Geometry -> Solid Geometry / Geometry in Space Minimum and Maximum Problems / Optimization Problems

I have a wooden cone, as shown in Fig. `1`. How am I to cut out of it the greatest possible cylinder? It will be seen that I can cut out one that is long and slender, like Fig. `2`, or short and thick, like Fig. `3`. But neither is the largest possible. A child could tell you where to cut, if he knew the rule. Can you find this simple rule?

Sources:Topics:Geometry -> Solid Geometry / Geometry in Space Minimum and Maximum Problems / Optimization Problems- Amusements in Mathematics, Henry Ernest Dudeney Question 202

-

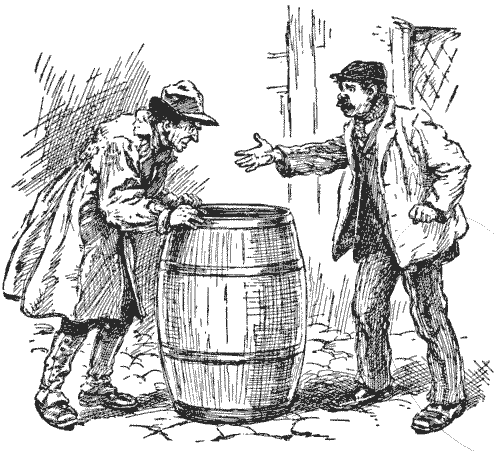

THE BARREL PUZZLE

The men in the illustration are disputing over the liquid contents of a barrel. What the particular liquid is it is impossible to say, for we are unable to look into the barrel; so we will call it water. One man says that the barrel is more than half full, while the other insists that it is not half full. What is their easiest way of settling the point? It is not necessary to use stick, string, or implement of any kind for measuring. I give this merely as one of the simplest possible examples of the value of ordinary sagacity in the solving of puzzles. What are apparently very difficult problems may frequently be solved in a similarly easy manner if we only use a little common sense. Sources:

Sources:

- Amusements in Mathematics, Henry Ernest Dudeney Question 364

-

A PACKING PUZZLE

As we all know by experience, considerable ingenuity is often required in packing articles into a box if space is not to be unduly wasted. A man once told me that he had a large number of iron balls, all exactly two inches in diameter, and he wished to pack as many of these as possible into a rectangular box `24` `9/10` inches long, `22` `4/5` inches wide, and `14` inches deep. Now, what is the greatest number of the balls that he could pack into that box?Sources:Topics:Geometry -> Solid Geometry / Geometry in Space Arithmetic Minimum and Maximum Problems / Optimization Problems- Amusements in Mathematics, Henry Ernest Dudeney Question 370

-

THE FIVE PENNIES

Here is a really hard puzzle, and yet its conditions are so absurdly simple. Every reader knows how to place four pennies so that they are equidistant from each other. All you have to do is to arrange three of them flat on the table so that they touch one another in the form of a triangle, and lay the fourth penny on top in the centre. Then, as every penny touches every other penny, they are all at equal distances from one another. Now try to do the same thing with five pennies—place them so that every penny shall touch every other penny—and you will find it a different matter altogether.Sources:Topics:Geometry -> Solid Geometry / Geometry in Space- Amusements in Mathematics, Henry Ernest Dudeney Question 419

-

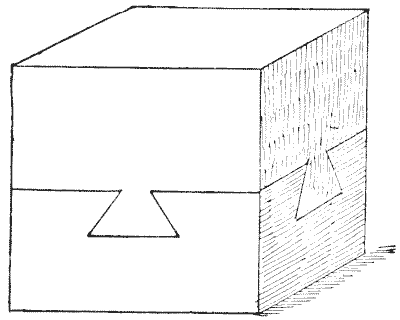

THE DOVETAILED BLOCK

Here is a curious mechanical puzzle that was given to me some years ago, but I cannot say who first invented it. It consists of two solid blocks of wood securely dovetailed together. On the other two vertical sides that are not visible the appearance is precisely the same as on those shown. How were the pieces put together? When I published this little puzzle in a London newspaper I received (though they were unsolicited) quite a stack of models, in oak, in teak, in mahogany, rosewood, satinwood, elm, and deal; some half a foot in length, and others varying in size right down to a delicate little model about half an inch square. It seemed to create considerable interest.

Sources:Topics:Geometry -> Solid Geometry / Geometry in Space

Here is a curious mechanical puzzle that was given to me some years ago, but I cannot say who first invented it. It consists of two solid blocks of wood securely dovetailed together. On the other two vertical sides that are not visible the appearance is precisely the same as on those shown. How were the pieces put together? When I published this little puzzle in a London newspaper I received (though they were unsolicited) quite a stack of models, in oak, in teak, in mahogany, rosewood, satinwood, elm, and deal; some half a foot in length, and others varying in size right down to a delicate little model about half an inch square. It seemed to create considerable interest.

Sources:Topics:Geometry -> Solid Geometry / Geometry in Space- Amusements in Mathematics, Henry Ernest Dudeney Question 424

-

Question

Suppose two pyramids are tangent to each other if they have no common interior points and they intersect in a non-degenerate planar polygon. Is it possible for 8 pyramids in space to all be tangent to each other?

A. AngelesSources:Topics:Combinatorics -> Combinatorial Geometry Proof and Example -> Constructing an Example / Counterexample Geometry -> Solid Geometry / Geometry in Space -> Polyhedra- Tournament of Towns, 1980-1981, Spring, Main Version, Grades 11-12 Question 1 Points 7

-

Question

Prove that there is no polyhedron with `7` edges.