Algebra, Word Problems

Word problems present mathematical challenges in a narrative or real-world context. Solving them requires translating the text into mathematical equations or expressions and then applying appropriate mathematical techniques. These can span arithmetic, algebra, geometry, etc.

Motion Problems Solving Word Problems "From the End" / Working Backwards-

CHINESE MONEY

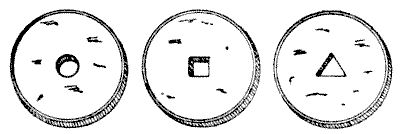

The Chinese are a curious people, and have strange inverted ways of doing things. It is said that they use a saw with an upward pressure instead of a downward one, that they plane a deal board by pulling the tool toward them instead of pushing it, and that in building a house they first construct the roof and, having raised that into position, proceed to work downwards. In money the currency of the country consists of taels of fluctuating value. The tael became thinner and thinner until `2,000` of them piled together made less than three inches in height. The common cash consists of brass coins of varying thicknesses, with a round, square, or triangular hole in the centre, as in our illustration. These are strung on wires like buttons. Supposing that eleven coins with round holes are worth fifteen ching-changs, that eleven with square holes are worth sixteen ching-changs, and that eleven with triangular holes are worth seventeen ching-changs, how can a Chinaman give me change for half a crown, using no coins other than the three mentioned? A ching-chang is worth exactly twopence and four-fifteenths of a ching-chang.

Sources:

These are strung on wires like buttons. Supposing that eleven coins with round holes are worth fifteen ching-changs, that eleven with square holes are worth sixteen ching-changs, and that eleven with triangular holes are worth seventeen ching-changs, how can a Chinaman give me change for half a crown, using no coins other than the three mentioned? A ching-chang is worth exactly twopence and four-fifteenths of a ching-chang.

Sources:

- Amusements in Mathematics, Henry Ernest Dudeney Question 25

-

THE JUNIOR CLERK'S PUZZLE

Two youths, bearing the pleasant names of Moggs and Snoggs, were employed as junior clerks by a merchant in Mincing Lane. They were both engaged at the same salary—that is, commencing at the rate of £`50` a year, payable half-yearly. Moggs had a yearly rise of £`10`, and Snoggs was offered the same, only he asked, for reasons that do not concern our puzzle, that he might take his rise at £`2, 10`s. half-yearly, to which his employer (not, perhaps, unnaturally!) had no objection.

Now we come to the real point of the puzzle. Moggs put regularly into the Post Office Savings Bank a certain proportion of his salary, while Snoggs saved twice as great a proportion of his, and at the end of five years they had together saved £`268, 15`s. How much had each saved? The question of interest can be ignored.

Sources:- Amusements in Mathematics, Henry Ernest Dudeney Question 26

-

GIVING CHANGE

Every one is familiar with the difficulties that frequently arise over the giving of change, and how the assistance of a third person with a few coins in his pocket will sometimes help us to set the matter right. Here is an example. An Englishman went into a shop in New York and bought goods at a cost of thirty-four cents. The only money he had was a dollar, a three-cent piece, and a two-cent piece. The tradesman had only a half-dollar and a quarter-dollar. But another customer happened to be present, and when asked to help produced two dimes, a five-cent piece, a two-cent piece, and a one-cent piece. How did the tradesman manage to give change? For the benefit of those readers who are not familiar with the American coinage, it is only necessary to say that a dollar is a hundred cents and a dime ten cents. A puzzle of this kind should rarely cause any difficulty if attacked in a proper manner. Sources:- Amusements in Mathematics, Henry Ernest Dudeney Question 27

-

THE BROKEN COINS

A man had three coins—a sovereign, a shilling, and a penny—and he found that exactly the same fraction of each coin had been broken away. Now, assuming that the original intrinsic value of these coins was the same as their nominal value—that is, that the sovereign was worth a pound, the shilling worth a shilling, and the penny worth a penny—what proportion of each coin has been lost if the value of the three remaining fragments is exactly one pound? Sources:- Amusements in Mathematics, Henry Ernest Dudeney Question 29

-

DOMESTIC ECONOMY

Young Mrs. Perkins, of Putney, writes to me as follows: "I should be very glad if you could give me the answer to a little sum that has been worrying me a good deal lately. Here it is: We have only been married a short time, and now, at the end of two years from the time when we set up housekeeping, my husband tells me that he finds we have spent a third of his yearly income in rent, rates, and taxes, one-half in domestic expenses, and one-ninth in other ways. He has a balance of £`190` remaining in the bank. I know this last, because he accidentally left out his pass-book the other day, and I peeped into it. Don't you think that a husband ought to give his wife his entire confidence in his money matters? Well, I do; and—will you believe it?—he has never told me what his income really is, and I want, very naturally, to find out. Can you tell me what it is from the figures I have given you?"

Yes; the answer can certainly be given from the figures contained in Mrs. Perkins's letter. And my readers, if not warned, will be practically unanimous in declaring the income to be—something absurdly in excess of the correct answer!

Sources:- Amusements in Mathematics, Henry Ernest Dudeney Question 31

-

A PUZZLE IN REVERSALS

Most people know that if you take any sum of money in pounds, shillings, and pence, in which the number of pounds (less than £`12`) exceeds that of the pence, reverse it (calling the pounds pence and the pence pounds), find the difference, then reverse and add this difference, the result is always £`12, 18`s. `11`d. But if we omit the condition, "less than £`12`," and allow nought to represent shillings or pence—(`1`) What is the lowest amount to which the rule will not apply? (`2`) What is the highest amount to which it will apply? Of course, when reversing such a sum as £`14, 15`s. `3`d. it may be written £`3, 16`s. `2`d., which is the same as £`3, 15`s. `14`d.Sources:Topics:Arithmetic Algebra -> Word Problems Combinatorics -> Case Analysis / Checking Cases -> Processes / Procedures- Amusements in Mathematics, Henry Ernest Dudeney Question 33

-

THE GROCER AND DRAPER

A country "grocer and draper" had two rival assistants, who prided themselves on their rapidity in serving customers. The young man on the grocery side could weigh up two one-pound parcels of sugar per minute, while the drapery assistant could cut three one-yard lengths of cloth in the same time. Their employer, one slack day, set them a race, giving the grocer a barrel of sugar and telling him to weigh up forty-eight one-pound parcels of sugar While the draper divided a roll of forty-eight yards of cloth into yard pieces. The two men were interrupted together by customers for nine minutes, but the draper was disturbed seventeen times as long as the grocer. What was the result of the race?Sources:Topics:Arithmetic Algebra -> Word Problems Algebra -> Inequalities -> Averages / Means Units of Measurement- Amusements in Mathematics, Henry Ernest Dudeney Question 34

-

JUDKINS'S CATTLE

Hiram B. Judkins, a cattle-dealer of Texas, had five droves of animals, consisting of oxen, pigs, and sheep, with the same number of animals in each drove. One morning he sold all that he had to eight dealers. Each dealer bought the same number of animals, paying seventeen dollars for each ox, four dollars for each pig, and two dollars for each sheep; and Hiram received in all three hundred and one dollars. What is the greatest number of animals he could have had? And how many would there be of each kind?Sources:Topics:Arithmetic Number Theory -> Modular Arithmetic / Remainder Arithmetic -> Divisibility Rules Algebra -> Word Problems Number Theory -> Division- Amusements in Mathematics, Henry Ernest Dudeney Question 35

-

BUYING APPLES

As the purchase of apples in small quantities has always presented considerable difficulties, I think it well to offer a few remarks on this subject. We all know the story of the smart boy who, on being told by the old woman that she was selling her apples at four for threepence, said: "Let me see! Four for threepence; that's three for twopence, two for a penny, one for nothing—I'll take one!"

There are similar cases of perplexity. For example, a boy once picked up a penny apple from a stall, but when he learnt that the woman's pears were the same price he exchanged it, and was about to walk off. "Stop!" said the woman. "You haven't paid me for the pear!" "No," said the boy, "of course not. I gave you the apple for it." "But you didn't pay for the apple!" "Bless the woman! You don't expect me to pay for the apple and the pear too!" And before the poor creature could get out of the tangle the boy had disappeared.

Then, again, we have the case of the man who gave a boy sixpence and promised to repeat the gift as soon as the youngster had made it into ninepence. Five minutes later the boy returned. "I have made it into ninepence," he said, at the same time handing his benefactor threepence. "How do you make that out?" he was asked. "I bought threepennyworth of apples." "But that does not make it into ninepence!" "I should rather think it did," was the boy's reply. "The apple woman has threepence, hasn't she? Very well, I have threepennyworth of apples, and I have just given you the other threepence. What's that but ninepence?"

I cite these cases just to show that the small boy really stands in need of a little instruction in the art of buying apples. So I will give a simple poser dealing with this branch of commerce.

An old woman had apples of three sizes for sale—one a penny, two a penny, and three a penny. Of course two of the second size and three of the third size were respectively equal to one apple of the largest size. Now, a gentleman who had an equal number of boys and girls gave his children sevenpence to be spent amongst them all on these apples. The puzzle is to give each child an equal distribution of apples. How was the sevenpence spent, and how many children were there?

Sources:Topics:Algebra -> Word Problems- Amusements in Mathematics, Henry Ernest Dudeney Question 36

-

BUYING CHESTNUTS

Though the following little puzzle deals with the purchase of chestnuts, it is not itself of the "chestnut" type. It is quite new. At first sight it has certainly the appearance of being of the "nonsense puzzle" character, but it is all right when properly considered.

A man went to a shop to buy chestnuts. He said he wanted a pennyworth, and was given five chestnuts. "It is not enough; I ought to have a sixth," he remarked! "But if I give you one chestnut more." the shopman replied, "you will have five too many." Now, strange to say, they were both right. How many chestnuts should the buyer receive for half a crown?

Sources:- Amusements in Mathematics, Henry Ernest Dudeney Question 37