Arithmetic

Arithmetic is the fundamental branch of mathematics dealing with numbers and the basic operations: addition, subtraction, multiplication, and division. Questions involve performing these operations, understanding number properties (like integers, fractions, decimals), and solving related word problems.

Fractions Percentages Division with Remainder-

A PRINTER'S ERROR

In a certain article a printer had to set up the figures `5^4xx2^3`, which, of course, means that the fourth power of `5` (`625`) is to be multiplied by the cube of `2` (`8`), the product of which is `5,000`. But he printed `5^4xx2^3` as `5\ 4\ 2\ 3`, which is not correct. Can you place four digits in the manner shown, so that it will be equally correct if the printer sets it up aright or makes the same blunder?

Sources:- Amusements in Mathematics, Henry Ernest Dudeney Question 115

-

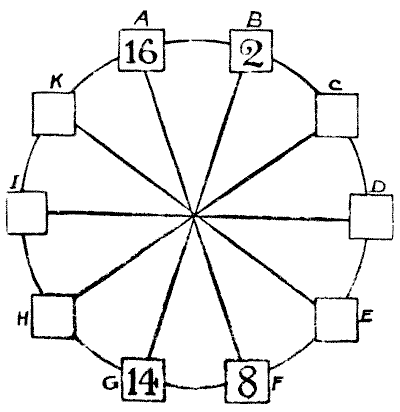

CIRCLING THE SQUARES

The puzzle is to place a different number in each of the ten squares so that the sum of the squares of any two adjacent numbers shall be equal to the sum of the squares of the two numbers diametrically opposite to them. The four numbers placed, as examples, must stand as they are. The square of `16` is `256`, and the square of `2` is `4`. Add these together, and the result is `260`. Also—the square of `14` is `196`, and the square of `8` is `64`. These together also make `260`. Now, in precisely the same way, B and C should be equal to G and H (the sum will not necessarily be `260`), A and K to F and E, H and I to C and D, and so on, with any two adjoining squares in the circle.

All you have to do is to fill in the remaining six numbers. Fractions are not allowed, and I shall show that no number need contain more than two figures.

Sources:- Amusements in Mathematics, Henry Ernest Dudeney Question 118

-

SIMPLE MULTIPLICATION

If we number six cards `1, 2, 4, 5, 7`, and `8`, and arrange them on the table in this order:—

`1\ \ \ 4\ \ \ 2\ \ \ 8\ \ \ 5\ \ \ 7`

We can demonstrate that in order to multiply by `3` all that is necessary is to remove the `1` to the other end of the row, and the thing is done. The answer is `428571`. Can you find a number that, when multiplied by `3` and divided by `2`, the answer will be the same as if we removed the first card (which in this case is to be a `3`) From the beginning of the row to the end?

Sources:Topics:Arithmetic Number Theory -> Modular Arithmetic / Remainder Arithmetic -> Divisibility Rules Number Theory -> Division- Amusements in Mathematics, Henry Ernest Dudeney Question 126

-

SIMPLE DIVISION

Sometimes a very simple question in elementary arithmetic will cause a good deal of perplexity. For example, I want to divide the four numbers, `701, 1,059, 1,417`, and `2,312`, by the largest number possible that will leave the same remainder in every case. How am I to set to work Of course, by a laborious system of trial one can in time discover the answer, but there is quite a simple method of doing it if you can only find it.Sources:Topics:Arithmetic Number Theory -> Greatest Common Divisor (GCD) and Least Common Multiple (LCM) -> Euclidean Algorithm Number Theory -> Division- Amusements in Mathematics, Henry Ernest Dudeney Question 127

-

THE SPANISH MISER

There once lived in a small town in New Castile a noted miser named Don Manuel Rodriguez. His love of money was only equalled by a strong passion for arithmetical problems. These puzzles usually dealt in some way or other with his accumulated treasure, and were propounded by him solely in order that he might have the pleasure of solving them himself. Unfortunately very few of them have survived, and when travelling through Spain, collecting material for a proposed work on "The Spanish Onion as a Cause of National Decadence," I only discovered a very few. One of these concerns the three boxes that appear in the accompanying authentic portrait. Each box contained a different number of golden doubloons. The difference between the number of doubloons in the upper box and the number in the middle box was the same as the difference between the number in the middle box and the number in the bottom box. And if the contents of any two of the boxes were united they would form a square number. What is the smallest number of doubloons that there could have been in any one of the boxes?

Sources:

Each box contained a different number of golden doubloons. The difference between the number of doubloons in the upper box and the number in the middle box was the same as the difference between the number in the middle box and the number in the bottom box. And if the contents of any two of the boxes were united they would form a square number. What is the smallest number of doubloons that there could have been in any one of the boxes?

Sources:

- Amusements in Mathematics, Henry Ernest Dudeney Question 131

-

THE FIVE BRIGANDS

The five Spanish brigands, Alfonso, Benito, Carlos, Diego, and Esteban, were counting their spoils after a raid, when it was found that they had captured altogether exactly `200` doubloons. One of the band pointed out that if Alfonso had twelve times as much, Benito three times as much, Carlos the same amount, Diego half as much, and Esteban one-third as much, they would still have altogether just `200` doubloons. How many doubloons had each?

There are a good many equally correct answers to this question. Here is one of them:

A 6 × 12 = 72 B 12 × 3 = 36 C 17 × 1 = 17 D 120 × ½ = 60 E 45 × 1/3 = 15 200 200 The puzzle is to discover exactly how many different answers there are, it being understood that every man had something and that there is to be no fractional money—only doubloons in every case.

This problem, worded somewhat differently, was propounded by Tartaglia (died `1559`), and he flattered himself that he had found one solution; but a French mathematician of note (M.A. Labosne), in a recent work, says that his readers will be astonished when he assures them that there are `6,639` different correct answers to the question. Is this so? How many answers are there?

Sources:Topics:Number Theory Arithmetic Algebra -> Word Problems Algebra -> Sequences -> Arithmetic Progression / Arithmetic Sequence Combinatorics -> Case Analysis / Checking Cases -> Processes / Procedures Algebra -> Equations -> Diophantine Equations- Amusements in Mathematics, Henry Ernest Dudeney Question 133

-

THE STONEMASON'S PROBLEM

A stonemason once had a large number of cubic blocks of stone in his yard, all of exactly the same size. He had some very fanciful little ways, and one of his queer notions was to keep these blocks piled in cubical heaps, no two heaps containing the same number of blocks. He had discovered for himself (a fact that is well known to mathematicians) that if he took all the blocks contained in any number of heaps in regular order, beginning with the single cube, he could always arrange those on the ground so as to form a perfect square. This will be clear to the reader, because one block is a square, `1+8 = 9` is a square, `1+8+27=36` is a square, `1+8+27+64=100` is a square, and so on. In fact, the sum of any number of consecutive cubes, beginning always with `1`, is in every case a square number.

One day a gentleman entered the mason's yard and offered him a certain price if he would supply him with a consecutive number of these cubical heaps which should contain altogether a number of blocks that could be laid out to form a square, but the buyer insisted on more than three heaps and declined to take the single block because it contained a flaw. What was the smallest possible number of blocks of stone that the mason had to supply?

Sources:- Amusements in Mathematics, Henry Ernest Dudeney Question 135

-

THE DUTCHMEN'S WIVES

I wonder how many of my readers are acquainted with the puzzle of the "Dutchmen's Wives"—in which you have to determine the names of three men's wives, or, rather, which wife belongs to each husband. Some thirty years ago it was "going the rounds," as something quite new, but I recently discovered it in the Ladies' Diary for `1739-40`, so it was clearly familiar to the fair sex over one hundred and seventy years ago. How many of our mothers, wives, sisters, daughters, and aunts could solve the puzzle to-day? A far greater proportion than then, let us hope.

Three Dutchmen, named Hendrick, Elas, and Cornelius, and their wives, Gurtrün, Katrün, and Anna, purchase hogs. Each buys as many as he (or she) gives shillings for one. Each husband pays altogether three guineas more than his wife. Hendrick buys twenty-three more hogs than Katrün, and Elas eleven more than Gurtrün. Now, what was the name of each man's wife?

Sources:Topics:Number Theory -> Prime Numbers Arithmetic Algebra -> Word Problems Algebra -> Equations -> Diophantine Equations

Sources:Topics:Number Theory -> Prime Numbers Arithmetic Algebra -> Word Problems Algebra -> Equations -> Diophantine Equations- Amusements in Mathematics, Henry Ernest Dudeney Question 139

-

MRS. SMILEY'S CHRISTMAS PRESENT

Mrs. Smiley's expression of pleasure was sincere when her six granddaughters sent to her, as a Christmas present, a very pretty patchwork quilt, which they had made with their own hands. It was constructed of square pieces of silk material, all of one size, and as they made a large quilt with fourteen of these little squares on each side, it is obvious that just `196` pieces had been stitched into it. Now, the six granddaughters each contributed a part of the work in the form of a perfect square (all six portions being different in size), but in order to join them up to form the square quilt it was necessary that the work of one girl should be unpicked into three separate pieces. Can you show how the joins might have been made? Of course, no portion can be turned over. Sources:Topics:Geometry Number Theory Arithmetic Combinatorics -> Combinatorial Geometry -> Cut a Shape / Dissection Problems

Sources:Topics:Geometry Number Theory Arithmetic Combinatorics -> Combinatorial Geometry -> Cut a Shape / Dissection Problems- Amusements in Mathematics, Henry Ernest Dudeney Question 172

-

A KITE-FLYING PUZZLE

While accompanying my friend Professor Highflite during a scientific kite-flying competition on the South Downs of Sussex I was led into a little calculation that ought to interest my readers. The Professor was paying out the wire to which his kite was attached from a winch on which it had been rolled into a perfectly spherical form. This ball of wire was just two feet in diameter, and the wire had a diameter of one-hundredth of an inch. What was the length of the wire?

Now, a simple little question like this that everybody can perfectly understand will puzzle many people to answer in any way. Let us see whether, without going into any profound mathematical calculations, we can get the answer roughly—say, within a mile of what is correct! We will assume that when the wire is all wound up the ball is perfectly solid throughout, and that no allowance has to be made for the axle that passes through it. With that simplification, I wonder how many readers can state within even a mile of the correct answer the length of that wire.

Sources:Topics:Geometry -> Solid Geometry / Geometry in Space Arithmetic Geometry -> Area Calculation Algebra -> Word Problems Units of Measurement- Amusements in Mathematics, Henry Ernest Dudeney Question 200