Geometry, Plane Geometry, Circles

This topic covers the properties of circles, including radius, diameter, circumference, area, chords, tangents, secants, arcs, and sectors. Questions involve calculations related to these elements and understanding theorems about angles and segments in circles.

Tangent to a Circle-

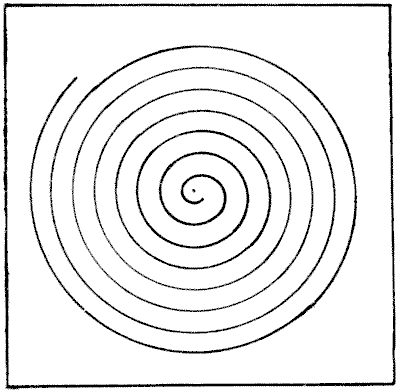

DRAWING A SPIRAL

If you hold the page horizontally and give it a quick rotary motion while looking at the centre of the spiral, it will appear to revolve. Perhaps a good many readers are acquainted with this little optical illusion. But the puzzle is to show how I was able to draw this spiral with so much exactitude without using anything but a pair of compasses and the sheet of paper on which the diagram was made. How would you proceed in such circumstances? Sources:Topics:Geometry -> Plane Geometry -> Circles

Sources:Topics:Geometry -> Plane Geometry -> Circles- Amusements in Mathematics, Henry Ernest Dudeney Question 183

-

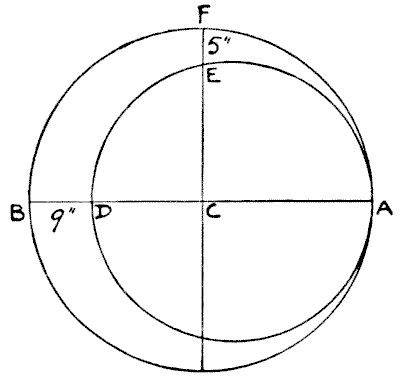

THE CRESCENT PUZZLE

Here is an easy geometrical puzzle. The crescent is formed by two circles, and C is the centre of the larger circle. The width of the crescent between B and D is `9` inches, and between E and F `5` inches. What are the diameters of the two circles?

Sources:

Here is an easy geometrical puzzle. The crescent is formed by two circles, and C is the centre of the larger circle. The width of the crescent between B and D is `9` inches, and between E and F `5` inches. What are the diameters of the two circles?

Sources:

- Amusements in Mathematics, Henry Ernest Dudeney Question 191

-

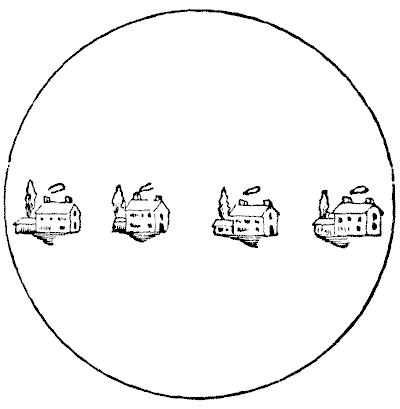

THE GARDEN WALLS

A speculative country builder has a circular field, on which he has erected four cottages, as shown in the illustration. The field is surrounded by a brick wall, and the owner undertook to put up three other brick walls, so that the neighbours should not be overlooked by each other, but the four tenants insist that there shall be no favouritism, and that each shall have exactly the same length of wall space for his wall fruit trees. The puzzle is to show how the three walls may be built so that each tenant shall have the same area of ground, and precisely the same length of wall.

Of course, each garden must be entirely enclosed by its walls, and it must be possible to prove that each garden has exactly the same length of wall. If the puzzle is properly solved no figures are necessary.

Sources:Topics:Geometry -> Area Calculation Geometry -> Plane Geometry -> Circles Combinatorics -> Combinatorial Geometry -> Cut a Shape / Dissection Problems- Amusements in Mathematics, Henry Ernest Dudeney Question 194

-

THE COMPASSES PUZZLE

It is curious how an added condition or restriction will sometimes convert an absurdly easy puzzle into an interesting and perhaps difficult one. I remember buying in the street many years ago a little mechanical puzzle that had a tremendous sale at the time. It consisted of a medal with holes in it, and the puzzle was to work a ring with a gap in it from hole to hole until it was finally detached. As I was walking along the street I very soon acquired the trick of taking off the ring with one hand while holding the puzzle in my pocket. A friend to whom I showed the little feat set about accomplishing it himself, and when I met him some days afterwards he exhibited his proficiency in the art. But he was a little taken aback when I then took the puzzle from him and, while simply holding the medal between the finger and thumb of one hand, by a series of little shakes and jerks caused the ring, without my even touching it, to fall off upon the floor. The following little poser will probably prove a rather tough nut for a great many readers, simply on account of the restricted conditions:—

Show how to find exactly the middle of any straight line by means of the compasses only. You are not allowed to use any ruler, pencil, or other article—only the compasses; and no trick or dodge, such as folding the paper, will be permitted. You must simply use the compasses in the ordinary legitimate way.

Sources:Topics:Geometry -> Plane Geometry -> Circles- Amusements in Mathematics, Henry Ernest Dudeney Question 197

-

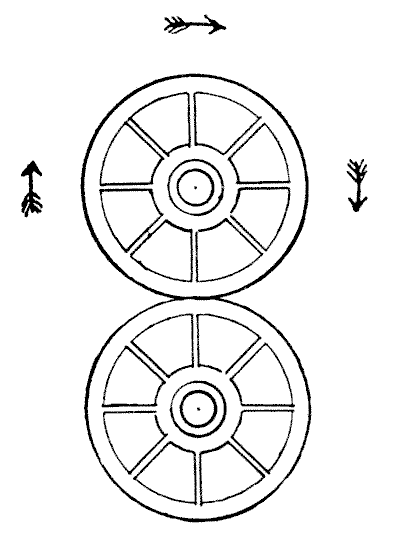

CONCERNING WHEELS

There are some curious facts concerning the movements of wheels that are apt to perplex the novice. For example: when a railway train is travelling from London to Crewe certain parts of the train at any given moment are actually moving from Crewe towards London. Can you indicate those parts? It seems absurd that parts of the same train can at any time travel in opposite directions, but such is the case.

In the accompanying illustration we have two wheels. The lower one is supposed to be fixed and the upper one running round it in the direction of the arrows. Now, how many times does the upper wheel turn on its own axis in making a complete revolution of the other wheel? Do not be in a hurry with your answer, or you are almost certain to be wrong. Experiment with two pennies on the table and the correct answer will surprise you, when you succeed in seeing it.

Sources:Topics:Geometry -> Plane Geometry -> Circles Geometry -> Plane Geometry -> Plane Transformations -> Congruence Transformations (Isometries) -> Rotation- Amusements in Mathematics, Henry Ernest Dudeney Question 203

-

PLACING HALFPENNIES

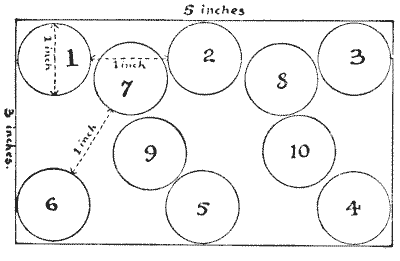

Here is an interesting little puzzle suggested to me by Mr. W. T. Whyte. Mark off on a sheet of paper a rectangular space `5` inches by `3` inches, and then find the greatest number of halfpennies that can be placed within the enclosure under the following conditions. A halfpenny is exactly an inch in diameter. Place your first halfpenny where you like, then place your second coin at exactly the distance of an inch from the first, the third an inch distance from the second, and so on. No halfpenny may touch another halfpenny or cross the boundary. Our illustration will make the matter perfectly clear. No. `2` coin is an inch from No. `1`; No. `3` an inch from No. `2`; No. `4` an inch from No. `3`; but after No. `10` is placed we can go no further in this attempt. Yet several more halfpennies might have been got in. How many can the reader place?

Sources:

Here is an interesting little puzzle suggested to me by Mr. W. T. Whyte. Mark off on a sheet of paper a rectangular space `5` inches by `3` inches, and then find the greatest number of halfpennies that can be placed within the enclosure under the following conditions. A halfpenny is exactly an inch in diameter. Place your first halfpenny where you like, then place your second coin at exactly the distance of an inch from the first, the third an inch distance from the second, and so on. No halfpenny may touch another halfpenny or cross the boundary. Our illustration will make the matter perfectly clear. No. `2` coin is an inch from No. `1`; No. `3` an inch from No. `2`; No. `4` an inch from No. `3`; but after No. `10` is placed we can go no further in this attempt. Yet several more halfpennies might have been got in. How many can the reader place?

Sources:

- Amusements in Mathematics, Henry Ernest Dudeney Question 429

-

Question

Consider an arbitrary triangle. Draw tangents to the inscribed circle parallel to the sides of the triangle. These tangents cut off three smaller triangles from the original triangle. Prove that the sum of the radii of the inscribed circles of these smaller triangles is equal to the radius of the inscribed circle of the original triangle.

Topics:Geometry -> Plane Geometry -> Circles -> Tangent to a Circle Geometry -> Plane Geometry -> Triangles -> Triangle Similarity