Logic, Reasoning / Logic

This category emphasizes general logical reasoning skills, often applied to puzzles or scenarios not strictly formal. It involves deduction, inference, identifying patterns, and drawing sound conclusions from given information. It overlaps with formal logic but can be broader.

Paradoxes-

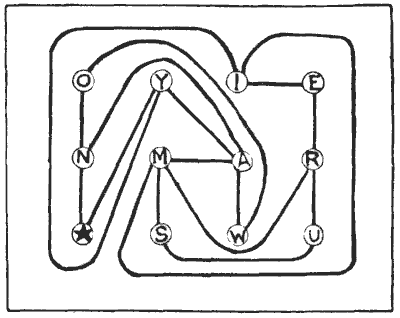

THE CYCLISTS' TOUR

Two cyclists were consulting a road map in preparation for a little tour together. The circles represent towns, and all the good roads are represented by lines. They are starting from the town with a star, and must complete their tour at E. But before arriving there they want to visit every other town once, and only once. That is the difficulty. Mr. Spicer said, "I am certain we can find a way of doing it;" but Mr. Maggs replied, "No way, I'm sure." Now, which of them was correct? Take your pencil and see if you can find any way of doing it. Of course you must keep to the roads indicated. Sources:

Sources:

- Amusements in Mathematics, Henry Ernest Dudeney Question 248

-

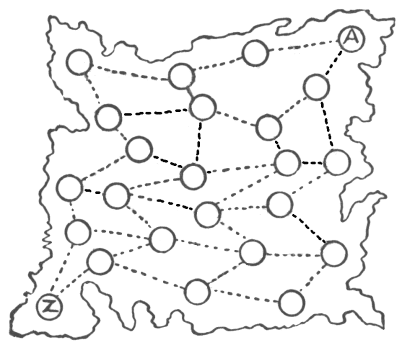

THE GRAND TOUR

One of the everyday puzzles of life is the working out of routes. If you are taking a holiday on your bicycle, or a motor tour, there always arises the question of how you are to make the best of your time and other resources. You have determined to get as far as some particular place, to include visits to such-and-such a town, to try to see something of special interest elsewhere, and perhaps to try to look up an old friend at a spot that will not take you much out of your way. Then you have to plan your route so as to avoid bad roads, uninteresting country, and, if possible, the necessity of a return by the same way that you went. With a map before you, the interesting puzzle is attacked and solved. I will present a little poser based on these lines.

I give a rough map of a country—it is not necessary to say what particular country—the circles representing towns and the dotted lines the railways connecting them. Now there lived in the town marked A a man who was born there, and during the whole of his life had never once left his native place. From his youth upwards he had been very industrious, sticking incessantly to his trade, and had no desire whatever to roam abroad. However, on attaining his fiftieth birthday he decided to see something of his country, and especially to pay a visit to a very old friend living at the town marked Z. What he proposed was this: that he would start from his home, enter every town once and only once, and finish his journey at Z. As he made up his mind to perform this grand tour by rail only, he found it rather a puzzle to work out his route, but he at length succeeded in doing so. How did he manage it? Do not forget that every town has to be visited once, and not more than once.

Sources:Topics:Combinatorics -> Combinatorial Geometry Combinatorics -> Graph Theory Logic -> Reasoning / Logic Combinatorics -> Case Analysis / Checking Cases -> Processes / Procedures Puzzles and Rebuses

Sources:Topics:Combinatorics -> Combinatorial Geometry Combinatorics -> Graph Theory Logic -> Reasoning / Logic Combinatorics -> Case Analysis / Checking Cases -> Processes / Procedures Puzzles and Rebuses- Amusements in Mathematics, Henry Ernest Dudeney Question 250

-

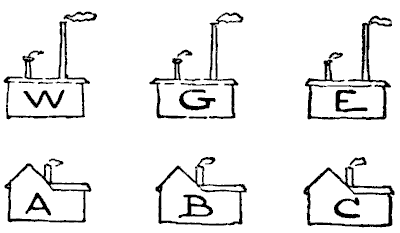

WATER, GAS, AND ELECTRICITY

There are some half-dozen puzzles, as old as the hills, that are perpetually cropping up, and there is hardly a month in the year that does not bring inquiries as to their solution. Occasionally one of these, that one had thought was an extinct volcano, bursts into eruption in a surprising manner. I have received an extraordinary number of letters respecting the ancient puzzle that I have called "Water, Gas, and Electricity." It is much older than electric lighting, or even gas, but the new dress brings it up to date. The puzzle is to lay on water, gas, and electricity, from W, G, and E, to each of the three houses, A, B, and C, without any pipe crossing another. Take your pencil and draw lines showing how this should be done. You will soon find yourself landed in difficulties. Sources:

Sources:

- Amusements in Mathematics, Henry Ernest Dudeney Question 251

-

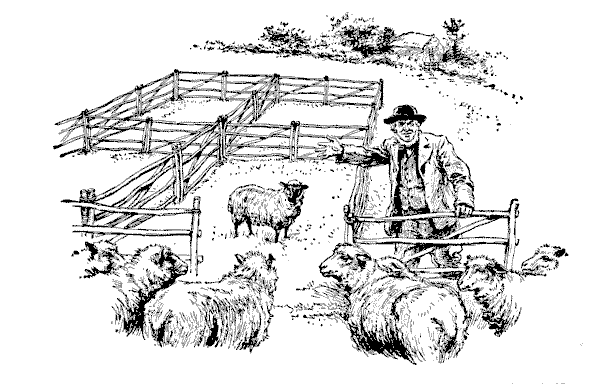

THOSE FIFTEEN SHEEP

A certain cyclopædia has the following curious problem, I am told: "Place fifteen sheep in four pens so that there shall be the same number of sheep in each pen." No answer whatever is vouchsafed, so I thought I would investigate the matter. I saw that in dealing with apples or bricks the thing would appear to be quite impossible, since four times any number must be an even number, while fifteen is an odd number. I thought, therefore, that there must be some quality peculiar to the sheep that was not generally known. So I decided to interview some farmers on the subject. The first one pointed out that if we put one pen inside another, like the rings of a target, and placed all sheep in the smallest pen, it would be all right. But I objected to this, because you admittedly place all the sheep in one pen, not in four pens. The second man said that if I placed four sheep in each of three pens and three sheep in the last pen (that is fifteen sheep in all), and one of the ewes in the last pen had a lamb during the night, there would be the same number in each pen in the morning. This also failed to satisfy me. The third farmer said, "I've got four hurdle pens down in one of my fields, and a small flock of wethers, so if you will just step down with me I will show you how it is done." The illustration depicts my friend as he is about to demonstrate the matter to me. His lucid explanation was evidently that which was in the mind of the writer of the article in the cyclopædia. What was it? Can you place those fifteen sheep?

Sources:Topics:Algebra -> Word Problems Logic -> Reasoning / Logic Combinatorics -> Case Analysis / Checking Cases -> Processes / Procedures Puzzles and Rebuses

The third farmer said, "I've got four hurdle pens down in one of my fields, and a small flock of wethers, so if you will just step down with me I will show you how it is done." The illustration depicts my friend as he is about to demonstrate the matter to me. His lucid explanation was evidently that which was in the mind of the writer of the article in the cyclopædia. What was it? Can you place those fifteen sheep?

Sources:Topics:Algebra -> Word Problems Logic -> Reasoning / Logic Combinatorics -> Case Analysis / Checking Cases -> Processes / Procedures Puzzles and Rebuses- Amusements in Mathematics, Henry Ernest Dudeney Question 262

-

THE ABBOT'S WINDOW

Once upon a time the Lord Abbot of St. Edmondsbury, in consequence of "devotions too strong for his head," fell sick and was unable to leave his bed. As he lay awake, tossing his head restlessly from side to side, the attentive monks noticed that something was disturbing his mind; but nobody dared ask what it might be, for the abbot was of a stern disposition, and never would brook inquisitiveness. Suddenly he called for Father John, and that venerable monk was soon at the bedside.

"Father John," said the Abbot, "dost thou know that I came into this wicked world on a Christmas Even?

"The monk nodded assent.

"And have I not often told thee that, having been born on Christmas Even, I have no love for the things that are odd? Look there!"

The Abbot pointed to the large dormitory window, of which I give a sketch. The monk looked, and was perplexed.

"Dost thou not see that the sixty-four lights add up an even number vertically and horizontally, but that all the diagonal lines, except fourteen are of a number that is odd? Why is this?"

"Of a truth, my Lord Abbot, it is of the very nature of things, and cannot be changed."

"Nay, but it shall be changed. I command thee that certain of the lights be closed this day, so that every line shall have an even number of lights. See thou that this be done without delay, lest the cellars be locked up for a month and other grievous troubles befall thee."

Father John was at his wits' end, but after consultation with one who was learned in strange mysteries, a way was found to satisfy the whim of the Lord Abbot. Which lights were blocked up, so that those which remained added up an even number in every line horizontally, vertically, and diagonally, while the least possible obstruction of light was caused?

Sources:Topics:Logic -> Reasoning / Logic Combinatorics -> Case Analysis / Checking Cases -> Processes / Procedures- Amusements in Mathematics, Henry Ernest Dudeney Question 292

-

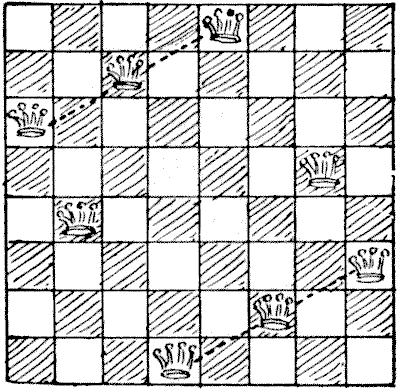

THE EIGHT QUEENS

The queen is by far the strongest piece on the chessboard. If you place her on one of the four squares in the centre of the board, she attacks no fewer than twenty-seven other squares; and if you try to hide her in a corner, she still attacks twenty-one squares. Eight queens may be placed on the board so that no queen attacks another, and it is an old puzzle (first proposed by Nauck in `1850`, and it has quite a little literature of its own) to discover in just how many different ways this may be done. I show one way in the diagram, and there are in all twelve of these fundamentally different ways. These twelve produce ninety-two ways if we regard reversals and reflections as different. The diagram is in a way a symmetrical arrangement. If you turn the page upside down, it will reproduce itself exactly; but if you look at it with one of the other sides at the bottom, you get another way that is not identical. Then if you reflect these two ways in a mirror you get two more ways. Now, all the other eleven solutions are non-symmetrical, and therefore each of them may be presented in eight ways by these reversals and reflections. It will thus be seen why the twelve fundamentally different solutions produce only ninety-two arrangements, as I have said, and not ninety-six, as would happen if all twelve were non-symmetrical. It is well to have a clear understanding on the matter of reversals and reflections when dealing with puzzles on the chessboard. Can the reader place the eight queens on the board so that no queen shall attack another and so that no three queens shall be in a straight line in any oblique direction? Another glance at the diagram will show that this arrangement will not answer the conditions, for in the two directions indicated by the dotted lines there are three queens in a straight line. There is only one of the twelve fundamental ways that will solve the puzzle. Can you find it?

Sources:

Can the reader place the eight queens on the board so that no queen shall attack another and so that no three queens shall be in a straight line in any oblique direction? Another glance at the diagram will show that this arrangement will not answer the conditions, for in the two directions indicated by the dotted lines there are three queens in a straight line. There is only one of the twelve fundamental ways that will solve the puzzle. Can you find it?

Sources:

- Amusements in Mathematics, Henry Ernest Dudeney Question 300

-

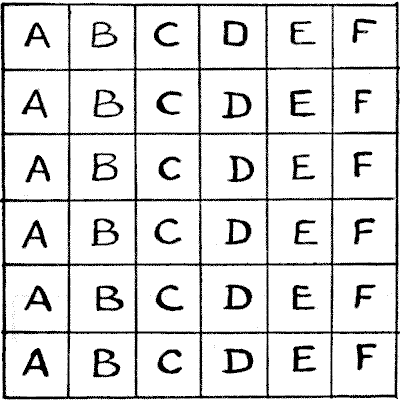

THE THIRTY-SIX LETTER BLOCKS

The illustration represents a box containing thirty-six letter-blocks. The puzzle is to rearrange these blocks so that no A shall be in a line vertically, horizontally, or diagonally with another A, no B with another B, no C with another C, and so on. You will find it impossible to get all the letters into the box under these conditions, but the point is to place as many as possible. Of course no letters other than those shown may be used.

Sources:Topics:Combinatorics -> Pigeonhole Principle Logic -> Reasoning / Logic Combinatorics -> Case Analysis / Checking Cases -> Processes / Procedures

The illustration represents a box containing thirty-six letter-blocks. The puzzle is to rearrange these blocks so that no A shall be in a line vertically, horizontally, or diagonally with another A, no B with another B, no C with another C, and so on. You will find it impossible to get all the letters into the box under these conditions, but the point is to place as many as possible. Of course no letters other than those shown may be used.

Sources:Topics:Combinatorics -> Pigeonhole Principle Logic -> Reasoning / Logic Combinatorics -> Case Analysis / Checking Cases -> Processes / Procedures- Amusements in Mathematics, Henry Ernest Dudeney Question 305

-

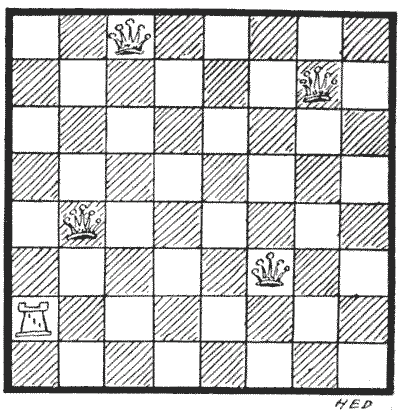

QUEENS AND BISHOP PUZZLE

It will be seen that every square of the board is either occupied or attacked. The puzzle is to substitute a bishop for the rook on the same square, and then place the four queens on other squares so that every square shall again be either occupied or attacked.

Sources:Topics:Logic -> Reasoning / Logic Combinatorics -> Case Analysis / Checking Cases -> Processes / Procedures Puzzles and Rebuses

Sources:Topics:Logic -> Reasoning / Logic Combinatorics -> Case Analysis / Checking Cases -> Processes / Procedures Puzzles and Rebuses- Amusements in Mathematics, Henry Ernest Dudeney Question 313

-

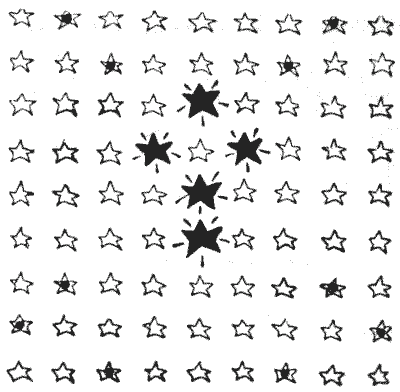

THE SOUTHERN CROSS

In the above illustration we have five Planets and eighty-one Fixed Stars, five of the latter being hidden by the Planets. It will be found that every Star, with the exception of the ten that have a black spot in their centres, is in a straight line, vertically, horizontally, or diagonally, with at least one of the Planets. The puzzle is so to rearrange the Planets that all the Stars shall be in line with one or more of them.

In rearranging the Planets, each of the five may be moved once in a straight line, in either of the three directions mentioned. They will, of course, obscure five other Stars in place of those at present covered.

Sources:Topics:Logic -> Reasoning / Logic Combinatorics -> Combinatorial Geometry -> Grid Paper Geometry / Lattice Geometry Puzzles and Rebuses- Amusements in Mathematics, Henry Ernest Dudeney Question 314

-

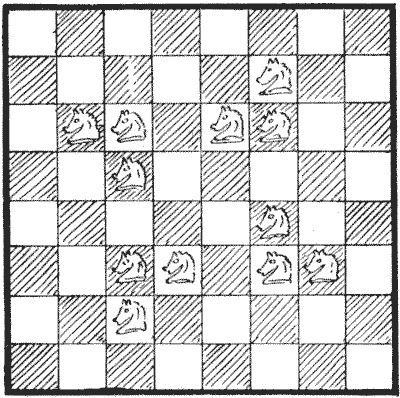

THE KNIGHT-GUARDS

The knight is the irresponsible low comedian of the chessboard. "He is a very uncertain, sneaking, and demoralizing rascal," says an American writer. "He can only move two squares, but makes up in the quality of his locomotion for its quantity, for he can spring one square sideways and one forward simultaneously, like a cat; can stand on one leg in the middle of the board and jump to any one of eight squares he chooses; can get on one side of a fence and blackguard three or four men on the other; has an objectionable way of inserting himself in safe places where he can scare the king and compel him to move, and then gobble a queen. For pure cussedness the knight has no equal, and when you chase him out of one hole he skips into another." Attempts have been made over and over again to obtain a short, simple, and exact definition of the move of the knight—without success. It really consists in moving one square like a rook, and then another square like a bishop—the two operations being done in one leap, so that it does not matter whether the first square passed over is occupied by another piece or not. It is, in fact, the only leaping move in chess. But difficult as it is to define, a child can learn it by inspection in a few minutes.

I have shown in the diagram how twelve knights (the fewest possible that will perform the feat) may be placed on the chessboard so that every square is either occupied or attacked by a knight. Examine every square in turn, and you will find that this is so. Now, the puzzle in this case is to discover what is the smallest possible number of knights that is required in order that every square shall be either occupied or attacked, and every knight protected by another knight. And how would you arrange them? It will be found that of the twelve shown in the diagram only four are thus protected by being a knight's move from another knight.

Sources:Topics:Combinatorics -> Combinatorial Geometry Logic -> Reasoning / Logic Combinatorics -> Case Analysis / Checking Cases -> Processes / Procedures- Amusements in Mathematics, Henry Ernest Dudeney Question 319