Logic, Reasoning / Logic

This category emphasizes general logical reasoning skills, often applied to puzzles or scenarios not strictly formal. It involves deduction, inference, identifying patterns, and drawing sound conclusions from given information. It overlaps with formal logic but can be broader.

Paradoxes-

PAINTING THE LAMP-POSTS

Tim Murphy and Pat Donovan were engaged by the local authorities to paint the lamp-posts in a certain street. Tim, who was an early riser, arrived first on the job, and had painted three on the south side when Pat turned up and pointed out that Tim's contract was for the north side. So Tim started afresh on the north side and Pat continued on the south. When Pat had finished his side he went across the street and painted six posts for Tim, and then the job was finished. As there was an equal number of lamp-posts on each side of the street, the simple question is: Which man painted the more lamp-posts, and just how many more? Sources:- Amusements in Mathematics, Henry Ernest Dudeney Question 103

-

SATURDAY MARKETING

Here is an amusing little case of marketing which, although it deals with a good many items of money, leads up to a question of a totally different character. Four married couples went into their village on a recent Saturday night to do a little marketing. They had to be very economical, for among them they only possessed forty shilling coins. The fact is, Ann spent `1`s., Mary spent `2`s., Jane spent `3`s., and Kate spent `4`s. The men were rather more extravagant than their wives, for Ned Smith spent as much as his wife, Tom Brown twice as much as his wife, Bill Jones three times as much as his wife, and Jack Robinson four times as much as his wife. On the way home somebody suggested that they should divide what coin they had left equally among them. This was done, and the puzzling question is simply this: What was the surname of each woman? Can you pair off the four couples?

Sources:- Amusements in Mathematics, Henry Ernest Dudeney Question 141

-

THE SHEEP-FOLD

It is a curious fact that the answers always given to some of the best-known puzzles that appear in every little book of fireside recreations that has been published for the last fifty or a hundred years are either quite unsatisfactory or clearly wrong. Yet nobody ever seems to detect their faults. Here is an example:—A farmer had a pen made of fifty hurdles, capable of holding a hundred sheep only. Supposing he wanted to make it sufficiently large to hold double that number, how many additional hurdles must he have? Sources:- Amusements in Mathematics, Henry Ernest Dudeney Question 193

-

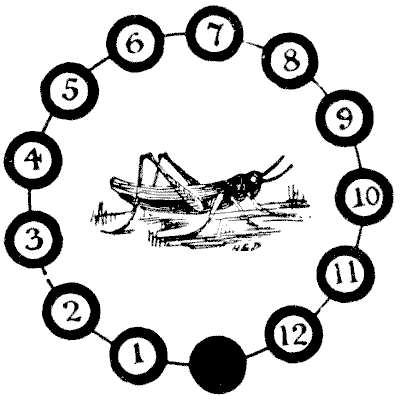

THE GRASSHOPPER PUZZLE

It has been suggested that this puzzle was a great favourite among the young apprentices of the City of London in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries. Readers will have noticed the curious brass grasshopper on the Royal Exchange. This long-lived creature escaped the fires of `1666` and `1838`. The grasshopper, after his kind, was the crest of Sir Thomas Gresham, merchant grocer, who died in `1579`, and from this cause it has been used as a sign by grocers in general. Unfortunately for the legend as to its origin, the puzzle was only produced by myself so late as the year `1900`. On twelve of the thirteen black discs are placed numbered counters or grasshoppers. The puzzle is to reverse their order, so that they shall read, `1, 2, 3, 4`, etc., in the opposite direction, with the vacant disc left in the same position as at present. Move one at a time in any order, either to the adjoining vacant disc or by jumping over one grasshopper, like the moves in draughts. The moves or leaps may be made in either direction that is at any time possible. What are the fewest possible moves in which it can be done? Sources:Topics:Logic -> Reasoning / Logic Combinatorics -> Case Analysis / Checking Cases -> Processes / Procedures

Sources:Topics:Logic -> Reasoning / Logic Combinatorics -> Case Analysis / Checking Cases -> Processes / Procedures- Amusements in Mathematics, Henry Ernest Dudeney Question 215

-

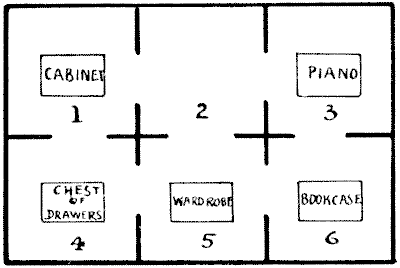

A LODGING-HOUSE DIFFICULTY

The Dobsons secured apartments at Slocomb-on-Sea. There were six rooms on the same floor, all communicating, as shown in the diagram. The rooms they took were numbers `4, 5`, and `6`, all facing the sea. But a little difficulty arose. Mr. Dobson insisted that the piano and the bookcase should change rooms. This was wily, for the Dobsons were not musical, but they wanted to prevent any one else playing the instrument. Now, the rooms were very small and the pieces of furniture indicated were very big, so that no two of these articles could be got into any room at the same time. How was the exchange to be made with the least possible labour? Suppose, for example, you first move the wardrobe into No. `2`; then you can move the bookcase to No. `5` and the piano to No. `6`, and so on. It is a fascinating puzzle, but the landlady had reasons for not appreciating it. Try to solve her difficulty in the fewest possible removals with counters on a sheet of paper.

Sources:

The Dobsons secured apartments at Slocomb-on-Sea. There were six rooms on the same floor, all communicating, as shown in the diagram. The rooms they took were numbers `4, 5`, and `6`, all facing the sea. But a little difficulty arose. Mr. Dobson insisted that the piano and the bookcase should change rooms. This was wily, for the Dobsons were not musical, but they wanted to prevent any one else playing the instrument. Now, the rooms were very small and the pieces of furniture indicated were very big, so that no two of these articles could be got into any room at the same time. How was the exchange to be made with the least possible labour? Suppose, for example, you first move the wardrobe into No. `2`; then you can move the bookcase to No. `5` and the piano to No. `6`, and so on. It is a fascinating puzzle, but the landlady had reasons for not appreciating it. Try to solve her difficulty in the fewest possible removals with counters on a sheet of paper.

Sources:

- Amusements in Mathematics, Henry Ernest Dudeney Question 220

-

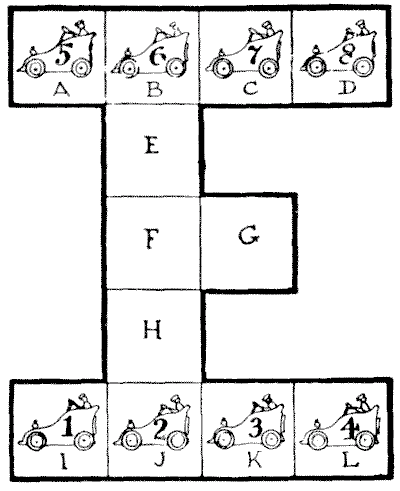

THE MOTOR-GARAGE PUZZLE

The difficulties of the proprietor of a motor garage are converted into a little pastime of a kind that has a peculiar fascination. All you need is to make a simple plan or diagram on a sheet of paper or cardboard and number eight counters, `1` to `8`. Then a whole family can enter into an amusing competition to find the best possible solution of the difficulty.

The illustration represents the plan of a motor garage, with accommodation for twelve cars. But the premises are so inconveniently restricted that the proprietor is often caused considerable perplexity. Suppose, for example, that the eight cars numbered `1` to `8` are in the positions shown, how are they to be shifted in the quickest possible way so that `1, 2, 3`, and `4` shall change places with `5, 6, 7`, and `8`—that is, with the numbers still running from left to right, as at present, but the top row exchanged with the bottom row? What are the fewest possible moves?

One car moves at a time, and any distance counts as one move. To prevent misunderstanding, the stopping-places are marked in squares, and only one car can be in a square at the same time.

Sources:Topics:Logic -> Reasoning / Logic Combinatorics -> Case Analysis / Checking Cases -> Processes / Procedures Combinatorics -> Case Analysis / Checking Cases -> Processes / Procedures Puzzles and Rebuses- Amusements in Mathematics, Henry Ernest Dudeney Question 224

-

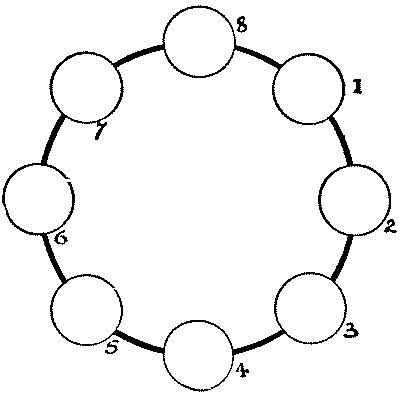

ROUND THE COAST

Here is a puzzle that will, I think, be found as amusing as instructive. We are given a ring of eight circles. Leaving circle `8` blank, we are required to write in the name of a seven-lettered port in the United Kingdom in this manner. Touch a blank circle with your pencil, then jump over two circles in either direction round the ring, and write down the first letter. Then touch another vacant circle, jump over two circles, and write down your second letter. Proceed similarly with the other letters in their proper order until you have completed the word. Thus, suppose we select "Glasgow," and proceed as follows: `6`—`1, 7`—`2, 8`—`3, 7`—`4, 8`—`5`, which means that we touch `6`, jump over `7` and and write down "G" on `1`; then touch `7`, jump over `8` and `1`, and write down "l" on `2`; and so on. It will be found that after we have written down the first five letters—"Glasg"—as above, we cannot go any further. Either there is something wrong with "Glasgow," or we have not managed our jumps properly. Can you get to the bottom of the mystery?

Sources:

Here is a puzzle that will, I think, be found as amusing as instructive. We are given a ring of eight circles. Leaving circle `8` blank, we are required to write in the name of a seven-lettered port in the United Kingdom in this manner. Touch a blank circle with your pencil, then jump over two circles in either direction round the ring, and write down the first letter. Then touch another vacant circle, jump over two circles, and write down your second letter. Proceed similarly with the other letters in their proper order until you have completed the word. Thus, suppose we select "Glasgow," and proceed as follows: `6`—`1, 7`—`2, 8`—`3, 7`—`4, 8`—`5`, which means that we touch `6`, jump over `7` and and write down "G" on `1`; then touch `7`, jump over `8` and `1`, and write down "l" on `2`; and so on. It will be found that after we have written down the first five letters—"Glasg"—as above, we cannot go any further. Either there is something wrong with "Glasgow," or we have not managed our jumps properly. Can you get to the bottom of the mystery?

Sources:

- Amusements in Mathematics, Henry Ernest Dudeney Question 226

-

THE EXCHANGE PUZZLE

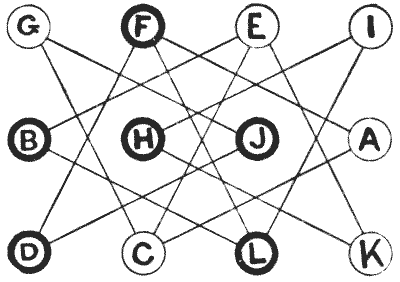

Here is a rather entertaining little puzzle with moving counters. You only need twelve counters—six of one colour, marked A, C, E, G, I, and K, and the other six marked B, D, F, H, J, and L. You first place them on the diagram, as shown in the illustration, and the puzzle is to get them into regular alphabetical order, as follows:—

A B C D E F G H I J K L The moves are made by exchanges of opposite colours standing on the same line. Thus, G and J may exchange places, or F and A, but you cannot exchange G and C, or F and D, because in one case they are both white and in the other case both black. Can you bring about the required arrangement in seventeen exchanges?

It cannot be done in fewer moves. The puzzle is really much easier than it looks, if properly attacked.

Sources:Topics:Combinatorics -> Invariants Logic -> Reasoning / Logic Combinatorics -> Case Analysis / Checking Cases -> Processes / Procedures Combinatorics -> Case Analysis / Checking Cases -> Processes / Procedures Puzzles and Rebuses- Amusements in Mathematics, Henry Ernest Dudeney Question 234

-

BOYS AND GIRLS

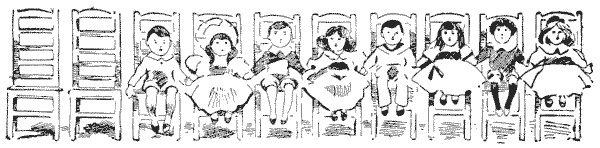

If you mark off ten divisions on a sheet of paper to represent the chairs, and use eight numbered counters for the children, you will have a fascinating pastime. Let the odd numbers represent boys and even numbers girls, or you can use counters of two colours, or coins.

The puzzle is to remove two children who are occupying adjoining chairs and place them in two empty chairs, making them first change sides; then remove a second pair of children from adjoining chairs and place them in the two now vacant, making them change sides; and so on, until all the boys are together and all the girls together, with the two vacant chairs at one end as at present. To solve the puzzle you must do this in five moves. The two children must always be taken from chairs that are next to one another; and remember the important point of making the two children change sides, as this latter is the distinctive feature of the puzzle. By "change sides" I simply mean that if, for example, you first move `1` and `2` to the vacant chairs, then the first (the outside) chair will be occupied by `2` and the second one by `1`.

Sources:

- Amusements in Mathematics, Henry Ernest Dudeney Question 237

-

ARRANGING THE JAMPOTS

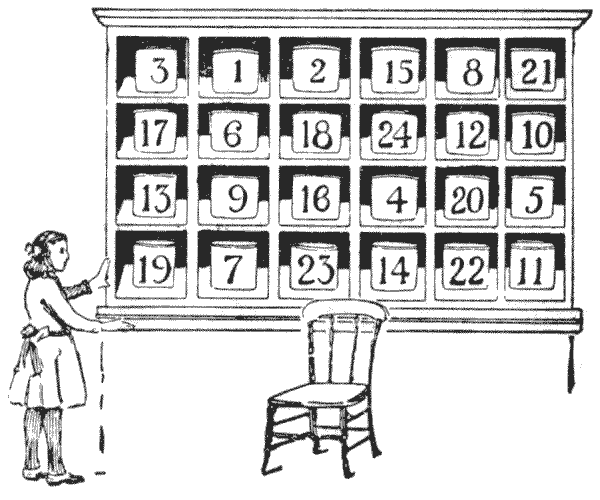

I happened to see a little girl sorting out some jam in a cupboard for her mother. She was putting each different kind of preserve apart on the shelves. I noticed that she took a pot of damson in one hand and a pot of gooseberry in the other and made them change places; then she changed a strawberry with a raspberry, and so on. It was interesting to observe what a lot of unnecessary trouble she gave herself by making more interchanges than there was any need for, and I thought it would work into a good puzzle.

It will be seen in the illustration that little Dorothy has to manipulate twenty-four large jampots in as many pigeon-holes. She wants to get them in correct numerical order—that is, `1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6` on the top shelf, `7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12` on the next shelf, and so on. Now, if she always takes one pot in the right hand and another in the left and makes them change places, how many of these interchanges will be necessary to get all the jampots in proper order? She would naturally first change the `1` and the `3`, then the `2` and the `3`, when she would have the first three pots in their places. How would you advise her to go on then? Place some numbered counters on a sheet of paper divided into squares for the pigeon-holes, and you will find it an amusing puzzle.

Sources:- Amusements in Mathematics, Henry Ernest Dudeney Question 238