Logic, Reasoning / Logic

This category emphasizes general logical reasoning skills, often applied to puzzles or scenarios not strictly formal. It involves deduction, inference, identifying patterns, and drawing sound conclusions from given information. It overlaps with formal logic but can be broader.

Paradoxes-

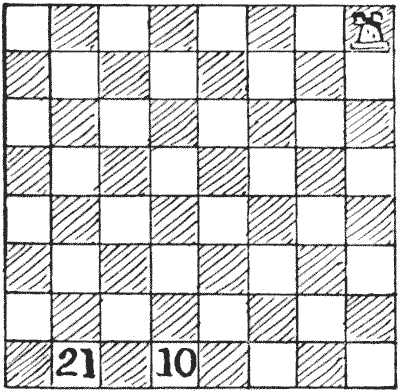

THE ROOK'S JOURNEY

This puzzle I call "The Rook's Journey," because the word "tour" (derived from a turner's wheel) implies that we return to the point from which we set out, and we do not do this in the present case. We should not be satisfied with a personally conducted holiday tour that ended by leaving us, say, in the middle of the Sahara. The rook here makes twenty-one moves, in the course of which journey it visits every square of the board once and only once, stopping at the square marked `10` at the end of its tenth move, and ending at the square marked `21`. Two consecutive moves cannot be made in the same direction—that is to say, you must make a turn after every move. Sources:Topics:Logic -> Reasoning / Logic Combinatorics -> Case Analysis / Checking Cases -> Processes / Procedures Combinatorics -> Combinatorial Geometry -> Grid Paper Geometry / Lattice Geometry Puzzles and Rebuses

Sources:Topics:Logic -> Reasoning / Logic Combinatorics -> Case Analysis / Checking Cases -> Processes / Procedures Combinatorics -> Combinatorial Geometry -> Grid Paper Geometry / Lattice Geometry Puzzles and Rebuses- Amusements in Mathematics, Henry Ernest Dudeney Question 321

-

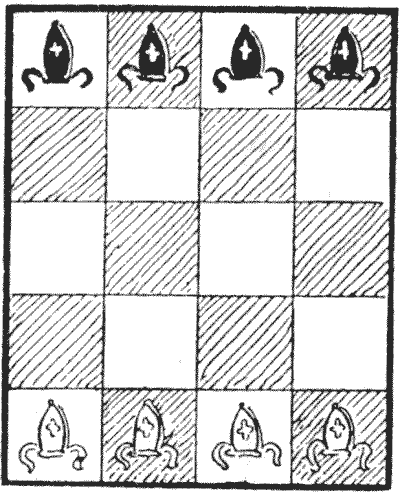

A NEW BISHOP'S PUZZLE

This is quite a fascinating little puzzle. Place eight bishops (four black and four white) on the reduced chessboard, as shown in the illustration. The problem is to make the black bishops change places with the white ones, no bishop ever attacking another of the opposite colour. They must move alternately—first a white, then a black, then a white, and so on. When you have succeeded in doing it at all, try to find the fewest possible moves.

If you leave out the bishops standing on black squares, and only play on the white squares, you will discover my last puzzle turned on its side.

Sources:Topics:Combinatorics -> Combinatorial Geometry Combinatorics -> Graph Theory Combinatorics -> Game Theory Logic -> Reasoning / Logic Puzzles and Rebuses- Amusements in Mathematics, Henry Ernest Dudeney Question 327

-

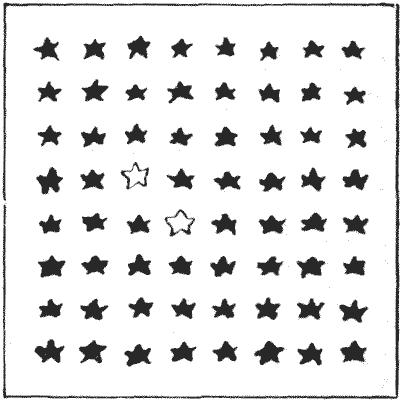

THE STAR PUZZLE

Put the point of your pencil on one of the white stars and (without ever lifting your pencil from the paper) strike out all the stars in fourteen continuous straight strokes, ending at the second white star. Your straight strokes may be in any direction you like, only every turning must be made on a star. There is no objection to striking out any star more than once.

In this case, where both your starting and ending squares are fixed inconveniently, you cannot obtain a solution by breaking a Queen's Tour, or in any other way by queen moves alone. But you are allowed to use oblique straight lines—such as from the upper white star direct to a corner star.

Sources:Topics:Combinatorics -> Combinatorial Geometry Combinatorics -> Graph Theory Logic -> Reasoning / Logic Puzzles and Rebuses- Amusements in Mathematics, Henry Ernest Dudeney Question 329

-

STALEMATE

Some years ago the puzzle was proposed to construct an imaginary game of chess, in which White shall be stalemated in the fewest possible moves with all the thirty-two pieces on the board. Can you build up such a position in fewer than twenty moves? Sources:- Amusements in Mathematics, Henry Ernest Dudeney Question 349

-

AN AMAZING DILEMMA

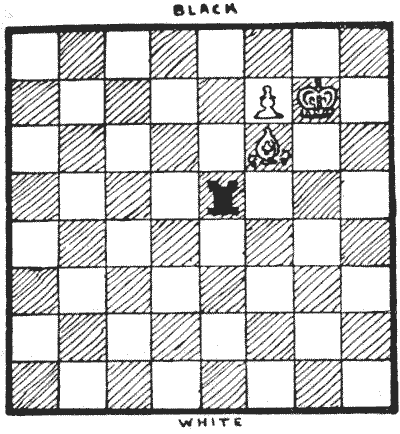

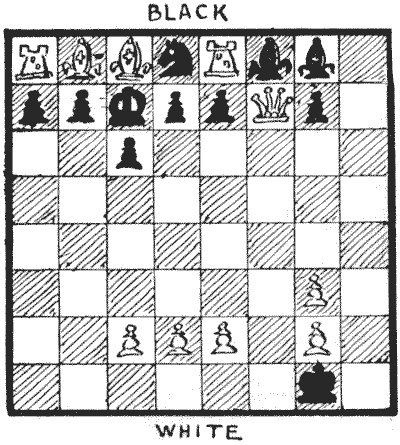

In a game of chess between Mr. Black and Mr. White, Black was in difficulties, and as usual was obliged to catch a train. So he proposed that White should complete the game in his absence on condition that no moves whatever should be made for Black, but only with the White pieces. Mr. White accepted, but to his dismay found it utterly impossible to win the game under such conditions. Try as he would, he could not checkmate his opponent. On which square did Mr. Black leave his king? The other pieces are in their proper positions in the diagram. White may leave Black in check as often as he likes, for it makes no difference, as he can never arrive at a checkmate position. Sources:

Sources:

- Amusements in Mathematics, Henry Ernest Dudeney Question 354

-

QUEER CHESS

Can you place two White rooks and a White knight on the board so that the Black king (who must be on one of the four squares in the middle of the board) shall be in check with no possible move open to him? "In other words," the reader will say, "the king is to be shown checkmated." Well, you can use the term if you wish, though I intentionally do not employ it myself. The mere fact that there is no White king on the board would be a sufficient reason for my not doing so. Sources:- Amusements in Mathematics, Henry Ernest Dudeney Question 356

-

CHESSBOARD SOLITAIRE

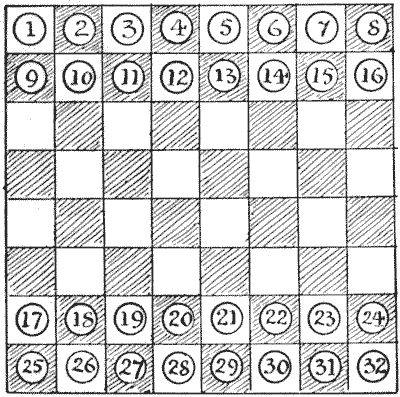

Here is an extension of the last game of solitaire. All you need is a chessboard and the thirty-two pieces, or the same number of draughts or counters. In the illustration numbered counters are used. The puzzle is to remove all the counters except two, and these two must have originally been on the same side of the board; that is, the two left must either belong to the group `1` to `16` or to the other group, `17` to `32`. You remove a counter by jumping over it with another counter to the next square beyond, if that square is vacant, but you cannot make a leap in a diagonal direction. The following moves will make the play quite clear: `3-11`, `4-12`, `3-4`, `13-3`. Here `3` jumps over `11`, and you remove `11`; `4` jumps over `12`, and you remove `12`; and so on. It will be found a fascinating little game of patience, and the solution requires the exercise of some ingenuity.

Sources:Topics:Combinatorics -> Game Theory Logic -> Reasoning / Logic Combinatorics -> Case Analysis / Checking Cases -> Processes / Procedures Puzzles and Rebuses

Here is an extension of the last game of solitaire. All you need is a chessboard and the thirty-two pieces, or the same number of draughts or counters. In the illustration numbered counters are used. The puzzle is to remove all the counters except two, and these two must have originally been on the same side of the board; that is, the two left must either belong to the group `1` to `16` or to the other group, `17` to `32`. You remove a counter by jumping over it with another counter to the next square beyond, if that square is vacant, but you cannot make a leap in a diagonal direction. The following moves will make the play quite clear: `3-11`, `4-12`, `3-4`, `13-3`. Here `3` jumps over `11`, and you remove `11`; `4` jumps over `12`, and you remove `12`; and so on. It will be found a fascinating little game of patience, and the solution requires the exercise of some ingenuity.

Sources:Topics:Combinatorics -> Game Theory Logic -> Reasoning / Logic Combinatorics -> Case Analysis / Checking Cases -> Processes / Procedures Puzzles and Rebuses- Amusements in Mathematics, Henry Ernest Dudeney Question 360

-

THE MONSTROSITY

One Christmas Eve I was travelling by rail to a little place in one of the southern counties. The compartment was very full, and the passengers were wedged in very tightly. My neighbour in one of the corner seats was closely studying a position set up on one of those little folding chessboards that can be carried conveniently in the pocket, and I could scarcely avoid looking at it myself. Here is the position:—

My fellow-passenger suddenly turned his head and caught the look of bewilderment on my face.

"Do you play chess?" he asked.

"Yes, a little. What is that? A problem?"

"Problem? No; a game."

"Impossible!" I exclaimed rather rudely. "The position is a perfect monstrosity!"

He took from his pocket a postcard and handed it to me. It bore an address at one side and on the other the words "`43`. K to Kt `8`."

"It is a correspondence game." he exclaimed. "That is my friend's last move, and I am considering my reply."

"But you really must excuse me; the position seems utterly impossible. How on earth, for example—"

"Ah!" he broke in smilingly. "I see; you are a beginner; you play to win."

"Of course you wouldn't play to lose or draw!"

He laughed aloud."You have much to learn. My friend and myself do not play for results of that antiquated kind. We seek in chess the wonderful, the whimsical, the weird. Did you ever see a position like that?"

I inwardly congratulated myself that I never had.

"That position, sir, materializes the sinuous evolvements and syncretic, synthetic, and synchronous concatenations of two cerebral individualities. It is the product of an amphoteric and intercalatory interchange of—"

"Have you seen the evening paper, sir?" interrupted the man opposite, holding out a newspaper. I noticed on the margin beside his thumb some pencilled writing. Thanking him, I took the paper and read—"Insane, but quite harmless. He is in my charge."

After that I let the poor fellow run on in his wild way until both got out at the next station.

But that queer position became fixed indelibly in my mind, with Black's last move `43`. K to Kt `8`; and a short time afterwards I found it actually possible to arrive at such a position in forty-three moves. Can the reader construct such a sequence? How did White get his rooks and king's bishop into their present positions, considering Black can never have moved his king's bishop? No odds were given, and every move was perfectly legitimate.

Sources:- Amusements in Mathematics, Henry Ernest Dudeney Question 361

-

THE WASSAIL BOWL

One Christmas Eve three Weary Willies came into possession of what was to them a veritable wassail bowl, in the form of a small barrel, containing exactly six quarts of fine ale. One of the men possessed a five-pint jug and another a three-pint jug, and the problem for them was to divide the liquor equally amongst them without waste. Of course, they are not to use any other vessels or measures. If you can show how it was to be done at all, then try to find the way that requires the fewest possible manipulations, every separate pouring from one vessel to another, or down a man's throat, counting as a manipulation.

Sources:Topics:Algebra -> Word Problems Logic -> Reasoning / Logic Combinatorics -> Case Analysis / Checking Cases -> Processes / Procedures Combinatorics -> Case Analysis / Checking Cases -> Processes / Procedures- Amusements in Mathematics, Henry Ernest Dudeney Question 362

-

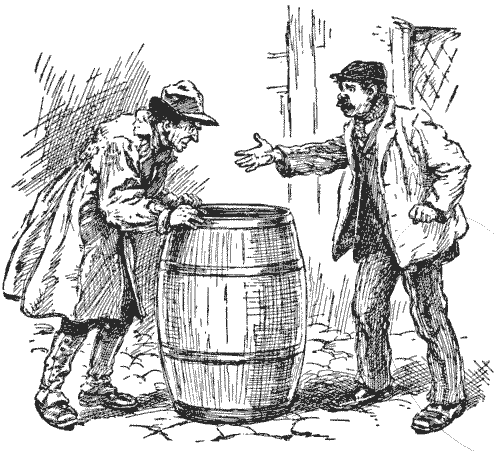

THE BARREL PUZZLE

The men in the illustration are disputing over the liquid contents of a barrel. What the particular liquid is it is impossible to say, for we are unable to look into the barrel; so we will call it water. One man says that the barrel is more than half full, while the other insists that it is not half full. What is their easiest way of settling the point? It is not necessary to use stick, string, or implement of any kind for measuring. I give this merely as one of the simplest possible examples of the value of ordinary sagacity in the solving of puzzles. What are apparently very difficult problems may frequently be solved in a similarly easy manner if we only use a little common sense. Sources:

Sources:

- Amusements in Mathematics, Henry Ernest Dudeney Question 364