Combinatorics, Combinatorial Geometry, Cut a Shape / Dissection Problems

Dissection problems involve cutting a given geometric shape into pieces that can be rearranged to form another specified shape, or to satisfy certain conditions (e.g., forming identical pieces). Questions test spatial reasoning and understanding of area preservation.

-

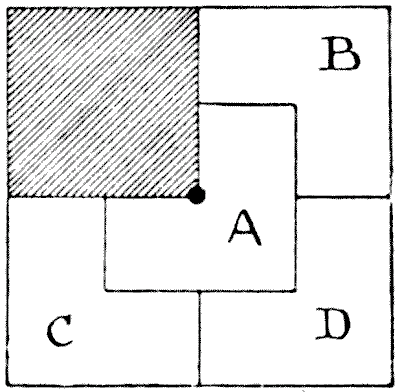

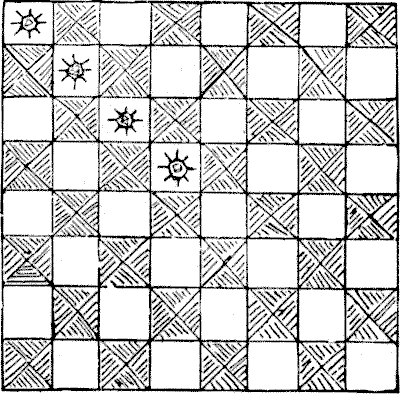

THE FOUR SONS

Readers will recognize the diagram as a familiar friend of their youth. A man possessed a square-shaped estate. He bequeathed to his widow the quarter of it that is shaded off. The remainder was to be divided equitably amongst his four sons, so that each should receive land of exactly the same area and exactly similar in shape. We are shown how this was done. But the remainder of the story is not so generally known. In the centre of the estate was a well, indicated by the dark spot, and Benjamin, Charles, and David complained that the division was not "equitable," since Alfred had access to this well, while they could not reach it without trespassing on somebody else's land. The puzzle is to show how the estate is to be apportioned so that each son shall have land of the same shape and area, and each have access to the well without going off his own land. Sources:Topics:Geometry -> Plane Geometry Geometry -> Area Calculation Combinatorics -> Combinatorial Geometry -> Cut a Shape / Dissection Problems

Sources:Topics:Geometry -> Plane Geometry Geometry -> Area Calculation Combinatorics -> Combinatorial Geometry -> Cut a Shape / Dissection Problems- Amusements in Mathematics, Henry Ernest Dudeney Question 180

-

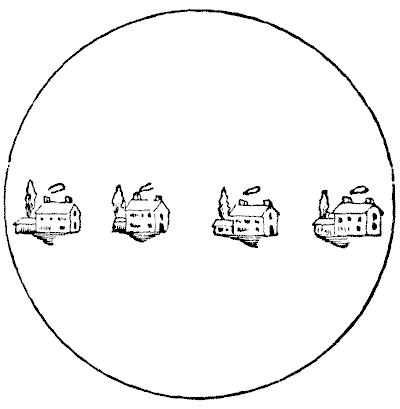

THE GARDEN WALLS

A speculative country builder has a circular field, on which he has erected four cottages, as shown in the illustration. The field is surrounded by a brick wall, and the owner undertook to put up three other brick walls, so that the neighbours should not be overlooked by each other, but the four tenants insist that there shall be no favouritism, and that each shall have exactly the same length of wall space for his wall fruit trees. The puzzle is to show how the three walls may be built so that each tenant shall have the same area of ground, and precisely the same length of wall.

Of course, each garden must be entirely enclosed by its walls, and it must be possible to prove that each garden has exactly the same length of wall. If the puzzle is properly solved no figures are necessary.

Sources:Topics:Geometry -> Area Calculation Geometry -> Plane Geometry -> Circles Combinatorics -> Combinatorial Geometry -> Cut a Shape / Dissection Problems- Amusements in Mathematics, Henry Ernest Dudeney Question 194

-

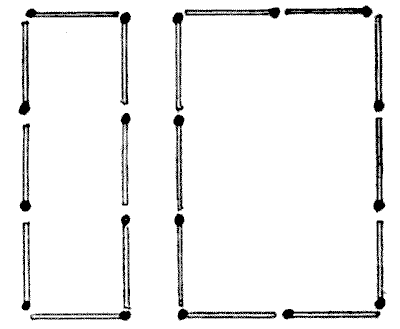

A NEW MATCH PUZZLE

In the illustration eighteen matches are shown arranged so that they enclose two spaces, one just twice as large as the other. Can you rearrange them (`1`) so as to enclose two four-sided spaces, one exactly three times as large as the other, and (`2`) so as to enclose two five-sided spaces, one exactly three times as large as the other? All the eighteen matches must be fairly used in each case; the two spaces must be quite detached, and there must be no loose ends or duplicated matches.

Sources:Topics:Geometry -> Area Calculation Combinatorics -> Combinatorial Geometry -> Cut a Shape / Dissection Problems Puzzles and Rebuses -> Matchstick Puzzles

In the illustration eighteen matches are shown arranged so that they enclose two spaces, one just twice as large as the other. Can you rearrange them (`1`) so as to enclose two four-sided spaces, one exactly three times as large as the other, and (`2`) so as to enclose two five-sided spaces, one exactly three times as large as the other? All the eighteen matches must be fairly used in each case; the two spaces must be quite detached, and there must be no loose ends or duplicated matches.

Sources:Topics:Geometry -> Area Calculation Combinatorics -> Combinatorial Geometry -> Cut a Shape / Dissection Problems Puzzles and Rebuses -> Matchstick Puzzles- Amusements in Mathematics, Henry Ernest Dudeney Question 204

-

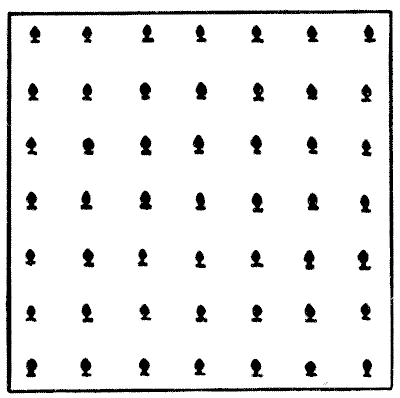

THE BURMESE PLANTATION

A short time ago I received an interesting communication from the British chaplain at Meiktila, Upper Burma, in which my correspondent informed me that he had found some amusement on board ship on his way out in trying to solve this little poser.

If he has a plantation of forty-nine trees, planted in the form of a square as shown in the accompanying illustration, he wishes to know how he may cut down twenty-seven of the trees so that the twenty-two left standing shall form as many rows as possible with four trees in every row.

Of course there may not be more than four trees in any row.

Sources:Topics:Combinatorics -> Case Analysis / Checking Cases -> Processes / Procedures Combinatorics -> Combinatorial Geometry -> Cut a Shape / Dissection Problems- Amusements in Mathematics, Henry Ernest Dudeney Question 212

-

CHEQUERED BOARD DIVISIONS

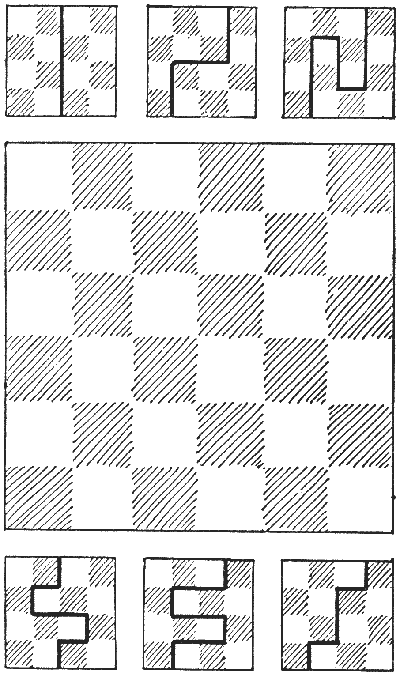

I recently asked myself the question: In how many different ways may a chessboard be divided into two parts of the same size and shape by cuts along the lines dividing the squares? The problem soon proved to be both fascinating and bristling with difficulties. I present it in a simplified form, taking a board of smaller dimensions. It is obvious that a board of four squares can only be so divided in one way—by a straight cut down the centre—because we shall not count reversals and reflections as different. In the case of a board of sixteen squares—four by four—there are just six different ways. I have given all these in the diagram, and the reader will not find any others. Now, take the larger board of thirty-six squares, and try to discover in how many ways it may be cut into two parts of the same size and shape.

Sources:Topics:Combinatorics -> Case Analysis / Checking Cases -> Processes / Procedures Combinatorics -> Combinatorial Geometry -> Cut a Shape / Dissection Problems

It is obvious that a board of four squares can only be so divided in one way—by a straight cut down the centre—because we shall not count reversals and reflections as different. In the case of a board of sixteen squares—four by four—there are just six different ways. I have given all these in the diagram, and the reader will not find any others. Now, take the larger board of thirty-six squares, and try to discover in how many ways it may be cut into two parts of the same size and shape.

Sources:Topics:Combinatorics -> Case Analysis / Checking Cases -> Processes / Procedures Combinatorics -> Combinatorial Geometry -> Cut a Shape / Dissection Problems- Amusements in Mathematics, Henry Ernest Dudeney Question 288

-

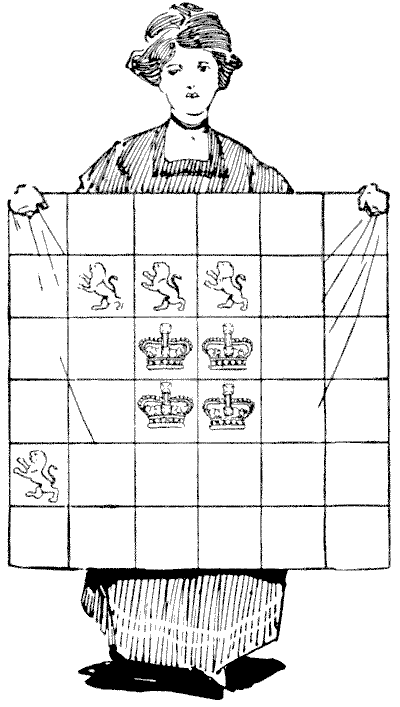

LIONS AND CROWNS

The young lady in the illustration is confronted with a little cutting-out difficulty in which the reader may be glad to assist her. She wishes, for some reason that she has not communicated to me, to cut that square piece of valuable material into four parts, all of exactly the same size and shape, but it is important that every piece shall contain a lion and a crown. As she insists that the cuts can only be made along the lines dividing the squares, she is considerably perplexed to find out how it is to be done. Can you show her the way? There is only one possible method of cutting the stuff. Sources:Topics:Combinatorics -> Combinatorial Geometry -> Cut a Shape / Dissection Problems Combinatorics -> Combinatorial Geometry -> Grid Paper Geometry / Lattice Geometry

Sources:Topics:Combinatorics -> Combinatorial Geometry -> Cut a Shape / Dissection Problems Combinatorics -> Combinatorial Geometry -> Grid Paper Geometry / Lattice Geometry- Amusements in Mathematics, Henry Ernest Dudeney Question 289

-

BOARDS WITH AN ODD NUMBER OF SQUARES

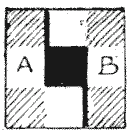

We will here consider the question of those boards that contain an odd number of squares. We will suppose that the central square is first cut out, so as to leave an even number of squares for division. Now, it is obvious that a square three by three can only be divided in one way, as shown in Fig. `1`. It will be seen that the pieces A and B are of the same size and shape, and that any other way of cutting would only produce the same shaped pieces, so remember that these variations are not counted as different ways. The puzzle I propose is to cut the board five by five (Fig. `2`) into two pieces of the same size and shape in as many different ways as possible. I have shown in the illustration one way of doing it. How many different ways are there altogether? A piece which when turned over resembles another piece is not considered to be of a different shape.

Sources:Topics:Geometry -> Plane Geometry -> Symmetry Combinatorics -> Combinatorial Geometry -> Cut a Shape / Dissection Problems Combinatorics -> Combinatorial Geometry -> Grid Paper Geometry / Lattice Geometry

Sources:Topics:Geometry -> Plane Geometry -> Symmetry Combinatorics -> Combinatorial Geometry -> Cut a Shape / Dissection Problems Combinatorics -> Combinatorial Geometry -> Grid Paper Geometry / Lattice Geometry- Amusements in Mathematics, Henry Ernest Dudeney Question 290

-

THE GRAND LAMA'S PROBLEM

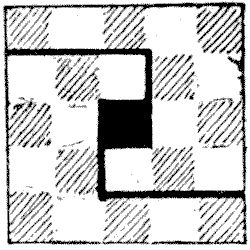

Once upon a time there was a Grand Lama who had a chessboard made of pure gold, magnificently engraved, and, of course, of great value. Every year a tournament was held at Lhassa among the priests, and whenever any one beat the Grand Lama it was considered a great honour, and his name was inscribed on the back of the board, and a costly jewel set in the particular square on which the checkmate had been given. After this sovereign pontiff had been defeated on four occasions he died—possibly of chagrin. Now the new Grand Lama was an inferior chess-player, and preferred other forms of innocent amusement, such as cutting off people's heads. So he discouraged chess as a degrading game, that did not improve either the mind or the morals, and abolished the tournament summarily. Then he sent for the four priests who had had the effrontery to play better than a Grand Lama, and addressed them as follows: "Miserable and heathenish men, calling yourselves priests! Know ye not that to lay claim to a capacity to do anything better than my predecessor is a capital offence? Take that chessboard and, before day dawns upon the torture chamber, cut it into four equal parts of the same shape, each containing sixteen perfect squares, with one of the gems in each part! If in this you fail, then shall other sports be devised for your special delectation. Go!" The four priests succeeded in their apparently hopeless task. Can you show how the board may be divided into four equal parts, each of exactly the same shape, by cuts along the lines dividing the squares, each part to contain one of the gems?

Sources:Topics:Combinatorics -> Colorings -> Chessboard Coloring Combinatorics -> Combinatorial Geometry -> Cut a Shape / Dissection Problems Puzzles and Rebuses

Now the new Grand Lama was an inferior chess-player, and preferred other forms of innocent amusement, such as cutting off people's heads. So he discouraged chess as a degrading game, that did not improve either the mind or the morals, and abolished the tournament summarily. Then he sent for the four priests who had had the effrontery to play better than a Grand Lama, and addressed them as follows: "Miserable and heathenish men, calling yourselves priests! Know ye not that to lay claim to a capacity to do anything better than my predecessor is a capital offence? Take that chessboard and, before day dawns upon the torture chamber, cut it into four equal parts of the same shape, each containing sixteen perfect squares, with one of the gems in each part! If in this you fail, then shall other sports be devised for your special delectation. Go!" The four priests succeeded in their apparently hopeless task. Can you show how the board may be divided into four equal parts, each of exactly the same shape, by cuts along the lines dividing the squares, each part to contain one of the gems?

Sources:Topics:Combinatorics -> Colorings -> Chessboard Coloring Combinatorics -> Combinatorial Geometry -> Cut a Shape / Dissection Problems Puzzles and Rebuses- Amusements in Mathematics, Henry Ernest Dudeney Question 291

-

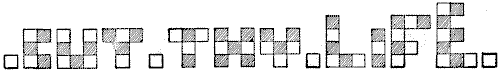

THE CHESSBOARD SENTENCE

I once set myself the amusing task of so dissecting an ordinary chessboard into letters of the alphabet that they would form a complete sentence. It will be seen from the illustration that the pieces assembled give the sentence, "CUT THY LIFE," with the stops between. The ideal sentence would, of course, have only one full stop, but that I did not succeed in obtaining.

The sentence is an appeal to the transgressor to cut himself adrift from the evil life he is living. Can you fit these pieces together to form a perfect chessboard?

Sources:Topics:Combinatorics -> Colorings -> Chessboard Coloring Combinatorics -> Combinatorial Geometry -> Cut a Shape / Dissection Problems Puzzles and Rebuses- Amusements in Mathematics, Henry Ernest Dudeney Question 294

-

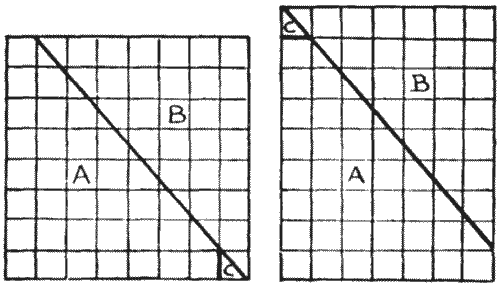

A CHESSBOARD FALLACY

"Here is a diagram of a chessboard," he said. "You see there are sixty-four squares—eight by eight. Now I draw a straight line from the top left-hand corner, where the first and second squares meet, to the bottom right-hand corner. I cut along this line with the scissors, slide up the piece that I have marked B, and then clip off the little corner C by a cut along the first upright line. This little piece will exactly fit into its place at the top, and we now have an oblong with seven squares on one side and nine squares on the other. There are, therefore, now only sixty-three squares, because seven multiplied by nine makes sixty-three. Where on earth does that lost square go to? I have tried over and over again to catch the little beggar, but he always eludes me. For the life of me I cannot discover where he hides himself."

"It seems to be like the other old chessboard fallacy, and perhaps the explanation is the same," said Reginald—"that the pieces do not exactly fit."

"But they do fit," said Uncle John. "Try it, and you will see."

Later in the evening Reginald and George, were seen in a corner with their heads together, trying to catch that elusive little square, and it is only fair to record that before they retired for the night they succeeded in securing their prey, though some others of the company failed to see it when captured. Can the reader solve the little mystery?

Sources:Topics:Geometry -> Plane Geometry Geometry -> Area Calculation Combinatorics -> Combinatorial Geometry -> Cut a Shape / Dissection Problems- Amusements in Mathematics, Henry Ernest Dudeney Question 413