Arithmetic

Arithmetic is the fundamental branch of mathematics dealing with numbers and the basic operations: addition, subtraction, multiplication, and division. Questions involve performing these operations, understanding number properties (like integers, fractions, decimals), and solving related word problems.

Fractions Percentages Division with Remainder-

THE WAPSHAW'S WHARF MYSTERY

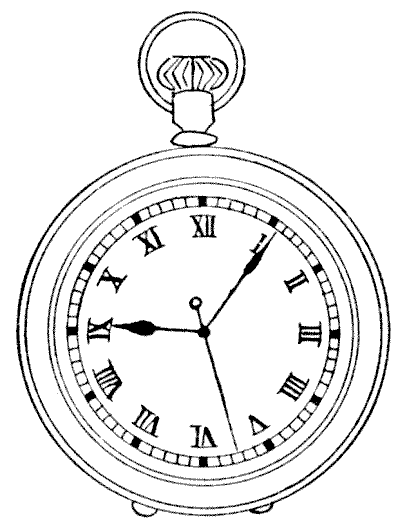

There was a great commotion in Lower Thames Street on the morning of January `12, 1887`. When the early members of the staff arrived at Wapshaw's Wharf they found that the safe had been broken open, a considerable sum of money removed, and the offices left in great disorder. The night watchman was nowhere to be found, but nobody who had been acquainted with him for one moment suspected him to be guilty of the robbery. In this belief the proprietors were confirmed when, later in the day, they were informed that the poor fellow's body had been picked up by the River Police. Certain marks of violence pointed to the fact that he had been brutally attacked and thrown into the river. A watch found in his pocket had stopped, as is invariably the case in such circumstances, and this was a valuable clue to the time of the outrage. But a very stupid officer (and we invariably find one or two stupid individuals in the most intelligent bodies of men) had actually amused himself by turning the hands round and round, trying to set the watch going again. After he had been severely reprimanded for this serious indiscretion, he was asked whether he could remember the time that was indicated by the watch when found. He replied that he could not, but he recollected that the hour hand and minute hand were exactly together, one above the other, and the second hand had just passed the forty-ninth second. More than this he could not remember.

What was the exact time at which the watchman's watch stopped? The watch is, of course, assumed to have been an accurate one.

Sources:- Amusements in Mathematics, Henry Ernest Dudeney Question 60

-

THE STOP-WATCH

We have here a stop-watch with three hands. The second hand, which travels once round the face in a minute, is the one with the little ring at its end near the centre. Our dial indicates the exact time when its owner stopped the watch. You will notice that the three hands are nearly equidistant. The hour and minute hands point to spots that are exactly a third of the circumference apart, but the second hand is a little too advanced. An exact equidistance for the three hands is not possible. Now, we want to know what the time will be when the three hands are next at exactly the same distances as shown from one another. Can you state the time?

Sources:

We have here a stop-watch with three hands. The second hand, which travels once round the face in a minute, is the one with the little ring at its end near the centre. Our dial indicates the exact time when its owner stopped the watch. You will notice that the three hands are nearly equidistant. The hour and minute hands point to spots that are exactly a third of the circumference apart, but the second hand is a little too advanced. An exact equidistance for the three hands is not possible. Now, we want to know what the time will be when the three hands are next at exactly the same distances as shown from one another. Can you state the time?

Sources:

- Amusements in Mathematics, Henry Ernest Dudeney Question 63

-

THE RAILWAY STATION CLOCK

A clock hangs on the wall of a railway station, `71` ft. `9` in. long and `10` ft. `4` in. high. Those are the dimensions of the wall, not of the clock! While waiting for a train we noticed that the hands of the clock were pointing in opposite directions, and were parallel to one of the diagonals of the wall. What was the exact time?Sources:Topics:Algebra -> Word Problems Arithmetic -> Fractions Geometry -> Plane Geometry -> Angle Calculation- Amusements in Mathematics, Henry Ernest Dudeney Question 65

-

ODD AND EVEN DIGITS

The odd digits, `1, 3, 5, 7`, and `9`, add up `25`, while the even figures, `2, 4, 6`, and `8`, only add up `20`. Arrange these figures so that the odd ones and the even ones add up alike. Complex and improper fractions and recurring decimals are not allowed.Sources:Topics:Arithmetic -> Fractions- Amusements in Mathematics, Henry Ernest Dudeney Question 78

-

THE CENTURY PUZZLE

Can you write `100` in the form of a mixed number, using all the nine digits once, and only once? The late distinguished French mathematician, Edouard Lucas, found seven different ways of doing it, and expressed his doubts as to there being any other ways. As a matter of fact there are just eleven ways and no more. Here is one of them, `91 5742/638`. Nine of the other ways have similarly two figures in the integral part of the number, but the eleventh expression has only one figure there. Can the reader find this last form?

Sources:Topics:Number Theory -> Modular Arithmetic / Remainder Arithmetic -> Divisibility Rules Logic -> Reasoning / Logic Arithmetic -> Fractions Combinatorics -> Case Analysis / Checking Cases -> Processes / Procedures- Amusements in Mathematics, Henry Ernest Dudeney Question 90

-

MORE MIXED FRACTIONS

When I first published my solution to the last puzzle, I was led to attempt the expression of all numbers in turn up to `100` by a mixed fraction containing all the nine digits. Here are twelve numbers for the reader to try his hand at: `13, 14, 15, 16, 18, 20, 27, 36, 40, 69, 72, 94`. Use every one of the nine digits once, and only once, in every case.

Sources:- Amusements in Mathematics, Henry Ernest Dudeney Question 91

-

THE FOUR SEVENS

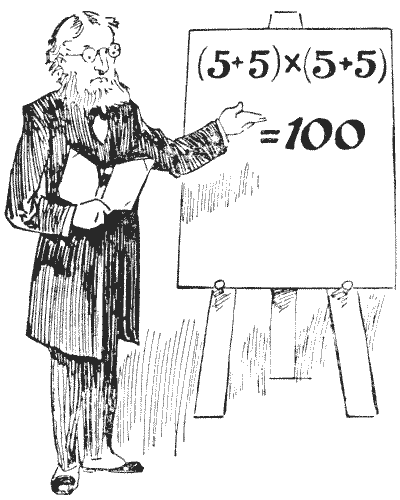

Sources: In the illustration Professor Rackbrane is seen demonstrating one of the little posers with which he is accustomed to entertain his class. He believes that by taking his pupils off the beaten tracks he is the better able to secure their attention, and to induce original and ingenious methods of thought. He has, it will be seen, just shown how four `5`'s may be written with simple arithmetical signs so as to represent `100`. Every juvenile reader will see at a glance that his example is quite correct. Now, what he wants you to do is this: Arrange four `7`'s (neither more nor less) with arithmetical signs so that they shall represent `100`. If he had said we were to use four `9`'s we might at once have written `99 9/9`, but the four `7`'s call for rather more ingenuity. Can you discover the little trick?

In the illustration Professor Rackbrane is seen demonstrating one of the little posers with which he is accustomed to entertain his class. He believes that by taking his pupils off the beaten tracks he is the better able to secure their attention, and to induce original and ingenious methods of thought. He has, it will be seen, just shown how four `5`'s may be written with simple arithmetical signs so as to represent `100`. Every juvenile reader will see at a glance that his example is quite correct. Now, what he wants you to do is this: Arrange four `7`'s (neither more nor less) with arithmetical signs so that they shall represent `100`. If he had said we were to use four `9`'s we might at once have written `99 9/9`, but the four `7`'s call for rather more ingenuity. Can you discover the little trick?- Amusements in Mathematics, Henry Ernest Dudeney Question 95

-

THE GREAT SCRAMBLE

After dinner, the five boys of a household happened to find a parcel of sugar-plums. It was quite unexpected loot, and an exciting scramble ensued, the full details of which I will recount with accuracy, as it forms an interesting puzzle.

You see, Andrew managed to get possession of just two-thirds of the parcel of sugar-plums. Bob at once grabbed three-eighths of these, and Charlie managed to seize three-tenths also. Then young David dashed upon the scene, and captured all that Andrew had left, except one-seventh, which Edgar artfully secured for himself by a cunning trick. Now the fun began in real earnest, for Andrew and Charlie jointly set upon Bob, who stumbled against the fender and dropped half of all that he had, which were equally picked up by David and Edgar, who had crawled under a table and were waiting. Next, Bob sprang on Charlie from a chair, and upset all the latter's collection on to the floor. Of this prize Andrew got just a quarter, Bob gathered up one-third, David got two-sevenths, while Charlie and Edgar divided equally what was left of that stock.

They were just thinking the fray was over when David suddenly struck out in two directions at once, upsetting three-quarters of what Bob and Andrew had last acquired. The two latter, with the greatest difficulty, recovered five-eighths of it in equal shares, but the three others each carried off one-fifth of the same. Every sugar-plum was now accounted for, and they called a truce, and divided equally amongst them the remainder of the parcel. What is the smallest number of sugar-plums there could have been at the start, and what proportion did each boy obtain?

Sources:- Amusements in Mathematics, Henry Ernest Dudeney Question 109

-

A PUZZLING LEGACY

A man left a hundred acres of land to be divided among his three sons—Alfred, Benjamin, and Charles—in the proportion of one-third, one-fourth, and one-fifth respectively. But Charles died. How was the land to be divided fairly between Alfred and Benjamin? Sources:- Amusements in Mathematics, Henry Ernest Dudeney Question 112

-

A LEGAL DIFFICULTY

"A client of mine," said a lawyer, "was on the point of death when his wife was about to present him with a child. I drew up his will, in which he settled two-thirds of his estate upon his son (if it should happen to be a boy) and one-third on the mother. But if the child should be a girl, then two-thirds of the estate should go to the mother and one-third to the daughter. As a matter of fact, after his death twins were born—a boy and a girl. A very nice point then arose. How was the estate to be equitably divided among the three in the closest possible accordance with the spirit of the dead man's will?" Sources:- Amusements in Mathematics, Henry Ernest Dudeney Question 123