Combinatorics

Combinatorics is the art of counting. It deals with selections, arrangements, and combinations of objects. Questions involve determining the number of ways to perform tasks, arrange items (permutations), or choose subsets (combinations), often using principles like the product rule and sum rule.

Pigeonhole Principle Double Counting Binomial Coefficients and Pascal's Triangle Product Rule / Rule of Product Graph Theory Matchings Induction (Mathematical Induction) Game Theory Combinatorial Geometry Invariants Case Analysis / Checking Cases Processes / Procedures Number Tables Colorings-

Question

There are 5778 extinguished lamps arranged at equal distances on a circle. Below each lamp is a button. Pressing a button changes the state of 4 lamps: the lamp next to the button, the next two lamps in the circle clockwise, and the lamp opposite the button (an extinguished lamp lights up when its state is changed, and a lit lamp is extinguished). What is the maximum number of lamps that can be lit simultaneously?

Sources:Topics:Combinatorics -> Combinatorial Geometry Combinatorics -> Invariants Logic -> Reasoning / Logic Number Theory -> Division -> Parity (Even/Odd) Combinatorics -> Case Analysis / Checking Cases -> Processes / Procedures Combinatorics -> Colorings

Sources:Topics:Combinatorics -> Combinatorial Geometry Combinatorics -> Invariants Logic -> Reasoning / Logic Number Theory -> Division -> Parity (Even/Odd) Combinatorics -> Case Analysis / Checking Cases -> Processes / Procedures Combinatorics -> Colorings- Beno Arbel Olympiad, 2017, Grade 8 Question 8

-

THE EXCURSION TICKET PUZZLE

When the big flaming placards were exhibited at the little provincial railway station, announcing that the Great —— Company would run cheap excursion trains to London for the Christmas holidays, the inhabitants of Mudley-cum-Turmits were in quite a flutter of excitement. Half an hour before the train came in the little booking office was crowded with country passengers, all bent on visiting their friends in the great Metropolis. The booking clerk was unaccustomed to dealing with crowds of such a dimension, and he told me afterwards, while wiping his manly brow, that what caused him so much trouble was the fact that these rustics paid their fares in such a lot of small money.

He said that he had enough farthings to supply a West End draper with change for a week, and a sufficient number of threepenny pieces for the congregations of three parish churches. "That excursion fare," said he, "is nineteen shillings and ninepence, and I should like to know in just how many different ways it is possible for such an amount to be paid in the current coin of this realm."

Here, then, is a puzzle: In how many different ways may nineteen shillings and ninepence be paid in our current coin? Remember that the fourpenny-piece is not now current.

Sources:Topics:Combinatorics- Amusements in Mathematics, Henry Ernest Dudeney Question 32

-

A PUZZLE IN REVERSALS

Most people know that if you take any sum of money in pounds, shillings, and pence, in which the number of pounds (less than £`12`) exceeds that of the pence, reverse it (calling the pounds pence and the pence pounds), find the difference, then reverse and add this difference, the result is always £`12, 18`s. `11`d. But if we omit the condition, "less than £`12`," and allow nought to represent shillings or pence—(`1`) What is the lowest amount to which the rule will not apply? (`2`) What is the highest amount to which it will apply? Of course, when reversing such a sum as £`14, 15`s. `3`d. it may be written £`3, 16`s. `2`d., which is the same as £`3, 15`s. `14`d.Sources:Topics:Arithmetic Algebra -> Word Problems Combinatorics -> Case Analysis / Checking Cases -> Processes / Procedures- Amusements in Mathematics, Henry Ernest Dudeney Question 33

-

DIGITS AND SQUARES

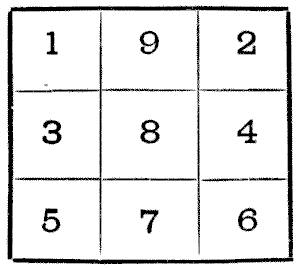

It will be seen in the diagram that we have so arranged the nine digits in a square that the number in the second row is twice that in the first row, and the number in the bottom row three times that in the top row. There are three other ways of arranging the digits so as to produce the same result. Can you find them?

Sources:Topics:Arithmetic Number Theory -> Modular Arithmetic / Remainder Arithmetic -> Divisibility Rules Combinatorics -> Case Analysis / Checking Cases -> Processes / Procedures

It will be seen in the diagram that we have so arranged the nine digits in a square that the number in the second row is twice that in the first row, and the number in the bottom row three times that in the top row. There are three other ways of arranging the digits so as to produce the same result. Can you find them?

Sources:Topics:Arithmetic Number Theory -> Modular Arithmetic / Remainder Arithmetic -> Divisibility Rules Combinatorics -> Case Analysis / Checking Cases -> Processes / Procedures- Amusements in Mathematics, Henry Ernest Dudeney Question 77

-

THE LOCKERS PUZZLE

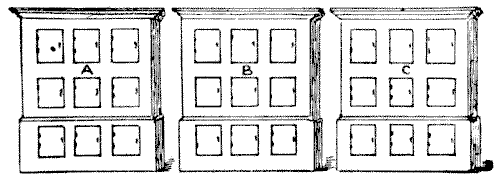

A man had in his office three cupboards, each containing nine lockers, as shown in the diagram. He told his clerk to place a different one-figure number on each locker of cupboard A, and to do the same in the case of B, and of C. As we are here allowed to call nought a digit, and he was not prohibited from using nought as a number, he clearly had the option of omitting any one of ten digits from each cupboard.

Now, the employer did not say the lockers were to be numbered in any numerical order, and he was surprised to find, when the work was done, that the figures had apparently been mixed up indiscriminately. Calling upon his clerk for an explanation, the eccentric lad stated that the notion had occurred to him so to arrange the figures that in each case they formed a simple addition sum, the two upper rows of figures producing the sum in the lowest row. But the most surprising point was this: that he had so arranged them that the addition in A gave the smallest possible sum, that the addition in C gave the largest possible sum, and that all the nine digits in the three totals were different. The puzzle is to show how this could be done. No decimals are allowed and the nought may not appear in the hundreds place.

Sources:Topics:Number Theory Arithmetic Logic -> Reasoning / Logic Combinatorics -> Case Analysis / Checking Cases -> Processes / Procedures- Amusements in Mathematics, Henry Ernest Dudeney Question 79

-

THE THREE GROUPS

There appeared in "Nouvelles Annales de Mathématiques" the following puzzle as a modification of one of my "Canterbury Puzzles." Arrange the nine digits in three groups of two, three, and four digits, so that the first two numbers when multiplied together make the third. Thus, `12` × `483` = `5,796`. I now also propose to include the cases where there are one, four, and four digits, such as `4` × `1,738` = `6,952`. Can you find all the possible solutions in both cases?Sources:Topics:Number Theory Arithmetic Combinatorics -> Case Analysis / Checking Cases -> Processes / Procedures- Amusements in Mathematics, Henry Ernest Dudeney Question 80

-

THE NINE COUNTERS

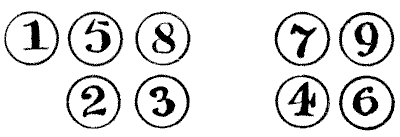

I have nine counters, each bearing one of the nine digits, `1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8` and `9`. I arranged them on the table in two groups, as shown in the illustration, so as to form two multiplication sums, and found that both sums gave the same product. You will find that `158` multiplied by `23` is `3,634`, and that `79` multiplied by `46` is also `3,634`. Now, the puzzle I propose is to rearrange the counters so as to get as large a product as possible. What is the best way of placing them? Remember both groups must multiply to the same amount, and there must be three counters multiplied by two in one case, and two multiplied by two counters in the other, just as at present.

Sources:

I have nine counters, each bearing one of the nine digits, `1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8` and `9`. I arranged them on the table in two groups, as shown in the illustration, so as to form two multiplication sums, and found that both sums gave the same product. You will find that `158` multiplied by `23` is `3,634`, and that `79` multiplied by `46` is also `3,634`. Now, the puzzle I propose is to rearrange the counters so as to get as large a product as possible. What is the best way of placing them? Remember both groups must multiply to the same amount, and there must be three counters multiplied by two in one case, and two multiplied by two counters in the other, just as at present.

Sources:

- Amusements in Mathematics, Henry Ernest Dudeney Question 81

-

THE TEN COUNTERS

In this case we use the nought in addition to the `1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9`. The puzzle is, as in the last case, so to arrange the ten counters that the products of the two multiplications shall be the same, and you may here have one or more figures in the multiplier, as you choose. The above is a very easy feat; but it is also required to find the two arrangements giving pairs of the highest and lowest products possible. Of course every counter must be used, and the cipher may not be placed to the left of a row of figures where it would have no effect. Vulgar fractions or decimals are not allowed.Sources:Topics:Arithmetic Combinatorics -> Case Analysis / Checking Cases -> Processes / Procedures Number Theory -> Division- Amusements in Mathematics, Henry Ernest Dudeney Question 82

-

DIGITAL MULTIPLICATION

Here is another entertaining problem with the nine digits, the nought being excluded. Using each figure once, and only once, we can form two multiplication sums that have the same product, and this may be done in many ways. For example, 7x658 and 14x329 contain all the digits once, and the product in each case is the same—`4,606`. Now, it will be seen that the sum of the digits in the product is `16`, which is neither the highest nor the lowest sum so obtainable. Can you find the solution of the problem that gives the lowest possible sum of digits in the common product? Also that which gives the highest possible sum?Sources:Topics:Number Theory Arithmetic Combinatorics -> Case Analysis / Checking Cases -> Processes / Procedures- Amusements in Mathematics, Henry Ernest Dudeney Question 83

-

THE PIERROT'S PUZZLE

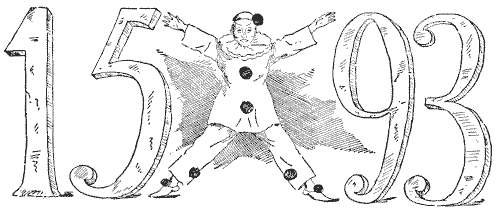

The Pierrot in the illustration is standing in a posture that represents the sign of multiplication. He is indicating the peculiar fact that `15` multiplied by `93` produces exactly the same figures (`1,395`), differently arranged. The puzzle is to take any four digits you like (all different) and similarly arrange them so that the number formed on one side of the Pierrot when multiplied by the number on the other side shall produce the same figures. There are very few ways of doing it, and I shall give all the cases possible. Can you find them all? You are allowed to put two figures on each side of the Pierrot as in the example shown, or to place a single figure on one side and three figures on the other. If we only used three digits instead of four, the only possible ways are these: `3` multiplied by `51` equals `153`, and `6` multiplied by `21` equals `126`.

Sources:Topics:Number Theory Arithmetic Combinatorics -> Case Analysis / Checking Cases -> Processes / Procedures

The Pierrot in the illustration is standing in a posture that represents the sign of multiplication. He is indicating the peculiar fact that `15` multiplied by `93` produces exactly the same figures (`1,395`), differently arranged. The puzzle is to take any four digits you like (all different) and similarly arrange them so that the number formed on one side of the Pierrot when multiplied by the number on the other side shall produce the same figures. There are very few ways of doing it, and I shall give all the cases possible. Can you find them all? You are allowed to put two figures on each side of the Pierrot as in the example shown, or to place a single figure on one side and three figures on the other. If we only used three digits instead of four, the only possible ways are these: `3` multiplied by `51` equals `153`, and `6` multiplied by `21` equals `126`.

Sources:Topics:Number Theory Arithmetic Combinatorics -> Case Analysis / Checking Cases -> Processes / Procedures- Amusements in Mathematics, Henry Ernest Dudeney Question 84