Combinatorics

Combinatorics is the art of counting. It deals with selections, arrangements, and combinations of objects. Questions involve determining the number of ways to perform tasks, arrange items (permutations), or choose subsets (combinations), often using principles like the product rule and sum rule.

Pigeonhole Principle Double Counting Binomial Coefficients and Pascal's Triangle Product Rule / Rule of Product Graph Theory Matchings Induction (Mathematical Induction) Game Theory Combinatorial Geometry Invariants Case Analysis / Checking Cases Processes / Procedures Number Tables Colorings-

THE CAB NUMBERS

A London policeman one night saw two cabs drive off in opposite directions under suspicious circumstances. This officer was a particularly careful and wide-awake man, and he took out his pocket-book to make an entry of the numbers of the cabs, but discovered that he had lost his pencil. Luckily, however, he found a small piece of chalk, with which he marked the two numbers on the gateway of a wharf close by. When he returned to the same spot on his beat he stood and looked again at the numbers, and noticed this peculiarity, that all the nine digits (no nought) were used and that no figure was repeated, but that if he multiplied the two numbers together they again produced the nine digits, all once, and once only. When one of the clerks arrived at the wharf in the early morning, he observed the chalk marks and carefully rubbed them out. As the policeman could not remember them, certain mathematicians were then consulted as to whether there was any known method for discovering all the pairs of numbers that have the peculiarity that the officer had noticed; but they knew of none. The investigation, however, was interesting, and the following question out of many was proposed: What two numbers, containing together all the nine digits, will, when multiplied together, produce another number (the highest possible) containing also all the nine digits? The nought is not allowed anywhere.Sources:Topics:Arithmetic Combinatorics Number Theory -> Modular Arithmetic / Remainder Arithmetic -> Divisibility Rules- Amusements in Mathematics, Henry Ernest Dudeney Question 85

-

THE NUMBER CHECKS PUZZLE

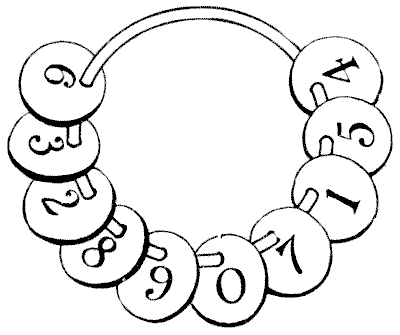

Where a large number of workmen are employed on a building it is customary to provide every man with a little disc bearing his number. These are hung on a board by the men as they arrive, and serve as a check on punctuality. Now, I once noticed a foreman remove a number of these checks from his board and place them on a split-ring which he carried in his pocket. This at once gave me the idea for a good puzzle. In fact, I will confide to my readers that this is just how ideas for puzzles arise. You cannot really create an idea: it happens—and you have to be on the alert to seize it when it does so happen. It will be seen from the illustration that there are ten of these checks on a ring, numbered `1` to `9` and `0`. The puzzle is to divide them into three groups without taking any off the ring, so that the first group multiplied by the second makes the third group. For example, we can divide them into the three groups, `2`—`8` `9` `7`—`1` `5` `4` `6` `3`, by bringing the `6` and the `3` round to the `4`, but unfortunately the first two when multiplied together do not make the third. Can you separate them correctly? Of course you may have as many of the checks as you like in any group. The puzzle calls for some ingenuity, unless you have the luck to hit on the answer by chance.

Sources:Topics:Number Theory Arithmetic Combinatorics -> Case Analysis / Checking Cases -> Processes / Procedures Puzzles and Rebuses

It will be seen from the illustration that there are ten of these checks on a ring, numbered `1` to `9` and `0`. The puzzle is to divide them into three groups without taking any off the ring, so that the first group multiplied by the second makes the third group. For example, we can divide them into the three groups, `2`—`8` `9` `7`—`1` `5` `4` `6` `3`, by bringing the `6` and the `3` round to the `4`, but unfortunately the first two when multiplied together do not make the third. Can you separate them correctly? Of course you may have as many of the checks as you like in any group. The puzzle calls for some ingenuity, unless you have the luck to hit on the answer by chance.

Sources:Topics:Number Theory Arithmetic Combinatorics -> Case Analysis / Checking Cases -> Processes / Procedures Puzzles and Rebuses- Amusements in Mathematics, Henry Ernest Dudeney Question 87

-

THE CENTURY PUZZLE

Can you write `100` in the form of a mixed number, using all the nine digits once, and only once? The late distinguished French mathematician, Edouard Lucas, found seven different ways of doing it, and expressed his doubts as to there being any other ways. As a matter of fact there are just eleven ways and no more. Here is one of them, `91 5742/638`. Nine of the other ways have similarly two figures in the integral part of the number, but the eleventh expression has only one figure there. Can the reader find this last form?

Sources:Topics:Number Theory -> Modular Arithmetic / Remainder Arithmetic -> Divisibility Rules Logic -> Reasoning / Logic Arithmetic -> Fractions Combinatorics -> Case Analysis / Checking Cases -> Processes / Procedures- Amusements in Mathematics, Henry Ernest Dudeney Question 90

-

THE DIGITAL CENTURY

`1\ 2\ 3\ 4\ 5\ 6\ 7\ 8\ 9 = 100`.

It is required to place arithmetical signs between the nine figures so that they shall equal `100`. Of course, you must not alter the present numerical arrangement of the figures. Can you give a correct solution that employs (`1`) the fewest possible signs, and (`2`) the fewest possible separate strokes or dots of the pen? That is, it is necessary to use as few signs as possible, and those signs should be of the simplest form. The signs of addition and multiplication (+ and ×) will thus count as two strokes, the sign of subtraction (-) as one stroke, the sign of division (÷) as three, and so on.

Sources:Topics:Arithmetic Combinatorics -> Case Analysis / Checking Cases -> Processes / Procedures Puzzles and Rebuses- Amusements in Mathematics, Henry Ernest Dudeney Question 94

-

THE DICE NUMBERS

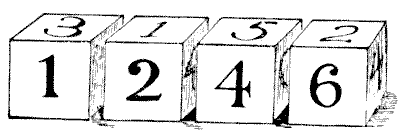

I have a set of four dice, not marked with spots in the ordinary way, but with Arabic figures, as shown in the illustration. Each die, of course, bears the numbers `1` to `6`. When put together they will form a good many, different numbers. As represented they make the number `1246`. Now, if I make all the different four-figure numbers that are possible with these dice (never putting the same figure more than once in any number), what will they all add up to? You are allowed to turn the `6` upside down, so as to represent a `9`. I do not ask, or expect, the reader to go to all the labour of writing out the full list of numbers and then adding them up. Life is not long enough for such wasted energy. Can you get at the answer in any other way?

Sources:- Amusements in Mathematics, Henry Ernest Dudeney Question 96

-

ACADEMIC COURTESIES

In a certain mixed school, where a special feature was made of the inculcation of good manners, they had a curious rule on assembling every morning. There were twice as many girls as boys. Every girl made a bow to every other girl, to every boy, and to the teacher. Every boy made a bow to every other boy, to every girl, and to the teacher. In all there were nine hundred bows made in that model academy every morning. Now, can you say exactly how many boys there were in the school? If you are not very careful, you are likely to get a good deal out in your calculation. Sources:- Amusements in Mathematics, Henry Ernest Dudeney Question 98

-

THE PARISH COUNCIL ELECTION

Here is an easy problem for the novice. At the last election of the parish council of Tittlebury-in-the-Marsh there were twenty-three candidates for nine seats. Each voter was qualified to vote for nine of these candidates or for any less number. One of the electors wants to know in just how many different ways it was possible for him to vote.Sources:Topics:Combinatorics- Amusements in Mathematics, Henry Ernest Dudeney Question 105

-

THE FIVE BRIGANDS

The five Spanish brigands, Alfonso, Benito, Carlos, Diego, and Esteban, were counting their spoils after a raid, when it was found that they had captured altogether exactly `200` doubloons. One of the band pointed out that if Alfonso had twelve times as much, Benito three times as much, Carlos the same amount, Diego half as much, and Esteban one-third as much, they would still have altogether just `200` doubloons. How many doubloons had each?

There are a good many equally correct answers to this question. Here is one of them:

A 6 × 12 = 72 B 12 × 3 = 36 C 17 × 1 = 17 D 120 × ½ = 60 E 45 × 1/3 = 15 200 200 The puzzle is to discover exactly how many different answers there are, it being understood that every man had something and that there is to be no fractional money—only doubloons in every case.

This problem, worded somewhat differently, was propounded by Tartaglia (died `1559`), and he flattered himself that he had found one solution; but a French mathematician of note (M.A. Labosne), in a recent work, says that his readers will be astonished when he assures them that there are `6,639` different correct answers to the question. Is this so? How many answers are there?

Sources:Topics:Number Theory Arithmetic Algebra -> Word Problems Algebra -> Sequences -> Arithmetic Progression / Arithmetic Sequence Combinatorics -> Case Analysis / Checking Cases -> Processes / Procedures Algebra -> Equations -> Diophantine Equations- Amusements in Mathematics, Henry Ernest Dudeney Question 133

-

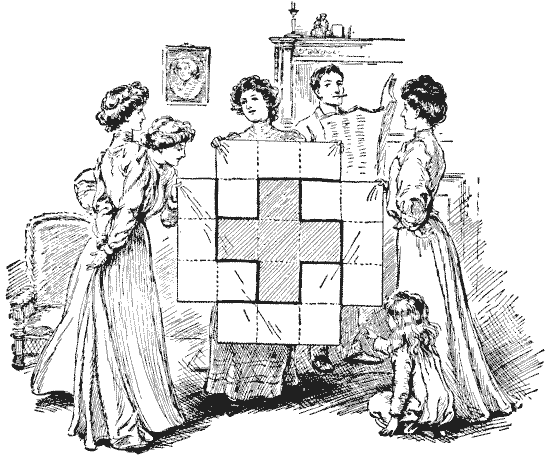

THE SILK PATCHWORK

The lady members of the Wilkinson family had made a simple patchwork quilt, as a small Christmas present, all composed of square pieces of the same size, as shown in the illustration. It only lacked the four corner pieces to make it complete. Somebody pointed out to them that if you unpicked the Greek cross in the middle and then cut the stitches along the dark joins, the four pieces all of the same size and shape would fit together and form a square. This the reader knows, from the solution in Fig. `39`, is quite easily done. But George Wilkinson suddenly suggested to them this poser. He said, "Instead of picking out the cross entire, and forming the square from four equal pieces, can you cut out a square entire and four equal pieces that will form a perfect Greek cross?" The puzzle is, of course, now quite easy. Sources:Topics:Geometry -> Plane Geometry Geometry -> Area Calculation Combinatorics -> Combinatorial Geometry -> Cut a Shape / Dissection Problems

Sources:Topics:Geometry -> Plane Geometry Geometry -> Area Calculation Combinatorics -> Combinatorial Geometry -> Cut a Shape / Dissection Problems- Amusements in Mathematics, Henry Ernest Dudeney Question 142

-

TWO CROSSES FROM ONE

Cut a Greek cross into five pieces that will form two such crosses, both of the same size. The solution of this puzzle is very beautiful. Sources:- Amusements in Mathematics, Henry Ernest Dudeney Question 143