Combinatorics

Combinatorics is the art of counting. It deals with selections, arrangements, and combinations of objects. Questions involve determining the number of ways to perform tasks, arrange items (permutations), or choose subsets (combinations), often using principles like the product rule and sum rule.

Pigeonhole Principle Double Counting Binomial Coefficients and Pascal's Triangle Product Rule / Rule of Product Graph Theory Matchings Induction (Mathematical Induction) Game Theory Combinatorial Geometry Invariants Case Analysis / Checking Cases Processes / Procedures Number Tables Colorings-

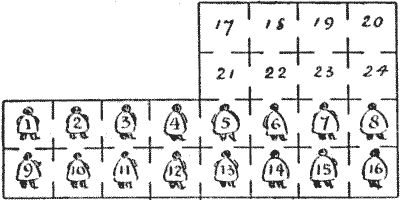

THE SIBERIAN DUNGEONS

The above is a trustworthy plan of a certain Russian prison in Siberia. All the cells are numbered, and the prisoners are numbered the same as the cells they occupy. The prison diet is so fattening that these political prisoners are in perpetual fear lest, should their pardon arrive, they might not be able to squeeze themselves through the narrow doorways and get out. And of course it would be an unreasonable thing to ask any government to pull down the walls of a prison just to liberate the prisoners, however innocent they might be. Therefore these men take all the healthy exercise they can in order to retard their increasing obesity, and one of their recreations will serve to furnish us with the following puzzle.

Show, in the fewest possible moves, how the sixteen men may form themselves into a magic square, so that the numbers on their backs shall add up the same in each of the four columns, four rows, and two diagonals without two prisoners having been at any time in the same cell together. I had better say, for the information of those who have not yet been made acquainted with these places, that it is a peculiarity of prisons that you are not allowed to go outside their walls. Any prisoner may go any distance that is possible in a single move.

Sources:Topics:Number Theory Combinatorics -> Case Analysis / Checking Cases -> Processes / Procedures Combinatorics -> Number Tables- Amusements in Mathematics, Henry Ernest Dudeney Question 404

-

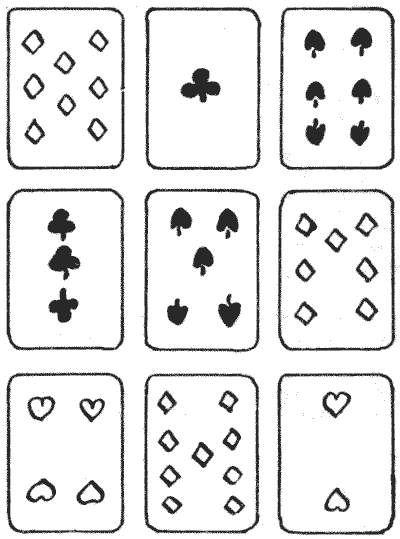

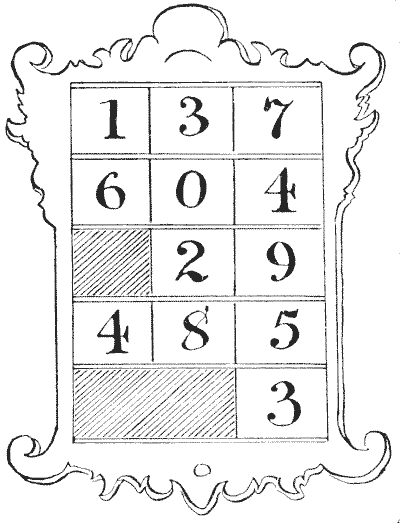

CARD MAGIC SQUARES

Take an ordinary pack of cards and throw out the twelve court cards. Now, with nine of the remainder (different suits are of no consequence) form the above magic square. It will be seen that the pips add up fifteen in every row in every column, and in each of the two long diagonals. The puzzle is with the remaining cards (without disturbing this arrangement) to form three more such magic squares, so that each of the four shall add up to a different sum. There will, of course, be four cards in the reduced pack that will not be used. These four may be any that you choose. It is not a difficult puzzle, but requires just a little thought.

Sources:Topics:Combinatorics -> Number Tables

Take an ordinary pack of cards and throw out the twelve court cards. Now, with nine of the remainder (different suits are of no consequence) form the above magic square. It will be seen that the pips add up fifteen in every row in every column, and in each of the two long diagonals. The puzzle is with the remaining cards (without disturbing this arrangement) to form three more such magic squares, so that each of the four shall add up to a different sum. There will, of course, be four cards in the reduced pack that will not be used. These four may be any that you choose. It is not a difficult puzzle, but requires just a little thought.

Sources:Topics:Combinatorics -> Number Tables- Amusements in Mathematics, Henry Ernest Dudeney Question 405

-

TWO NEW MAGIC SQUARES

Construct a subtracting magic square with the first sixteen whole numbers that shall be "associated" by subtraction. The constant is, of course, obtained by subtracting the first number from the second in line, the result from the third, and the result again from the fourth. Also construct a dividing magic square of the same order that shall be "associated" by division. The constant is obtained by dividing the second number in a line by the first, the third by the quotient, and the fourth by the next quotient.Sources:Topics:Combinatorics -> Number Tables- Amusements in Mathematics, Henry Ernest Dudeney Question 407

-

MAGIC SQUARES OF TWO DEGREES

While reading a French mathematical work I happened to come across, the following statement: "A very remarkable magic square of `8`, in two degrees, has been constructed by M. Pfeffermann. In other words, he has managed to dispose the sixty-four first numbers on the squares of a chessboard in such a way that the sum of the numbers in every line, every column, and in each of the two diagonals, shall be the same; and more, that if one substitutes for all the numbers their squares, the square still remains magic." I at once set to work to solve this problem, and, although it proved a very hard nut, one was rewarded by the discovery of some curious and beautiful laws that govern it. The reader may like to try his hand at the puzzle.

Sources:- Amusements in Mathematics, Henry Ernest Dudeney Question 408

-

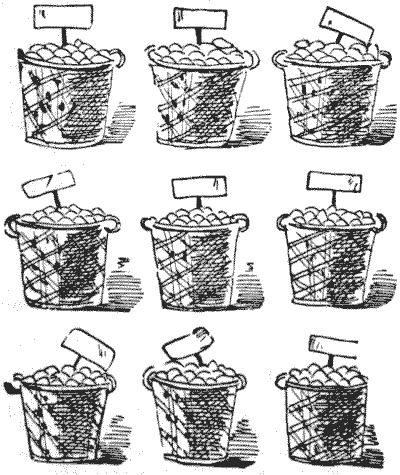

THE BASKETS OF PLUMS

This is the form in which I first introduced the question of magic squares with prime numbers. I will here warn the reader that there is a little trap.

A fruit merchant had nine baskets. Every basket contained plums (all sound and ripe), and the number in every basket was different. When placed as shown in the illustration they formed a magic square, so that if he took any three baskets in a line in the eight possible directions there would always be the same number of plums. This part of the puzzle is easy enough to understand. But what follows seems at first sight a little queer.

The merchant told one of his men to distribute the contents of any basket he chose among some children, giving plums to every child so that each should receive an equal number. But the man found it quite impossible, no matter which basket he selected and no matter how many children he included in the treat. Show, by giving contents of the nine baskets, how this could come about.

Sources:- Amusements in Mathematics, Henry Ernest Dudeney Question 409

-

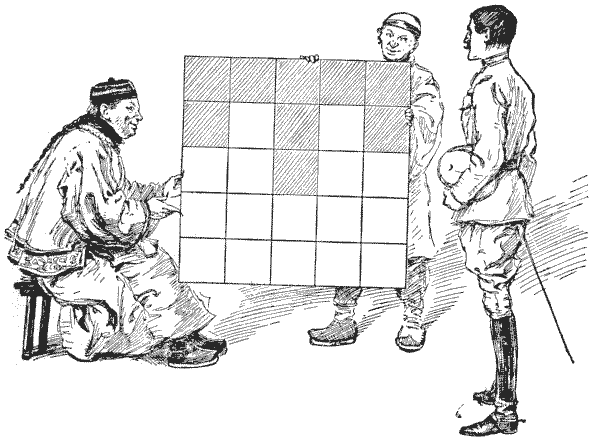

THE MANDARIN'S "T" PUZZLE

Before Mr. Beauchamp Cholmondely Marjoribanks set out on his tour in the Far East, he prided himself on his knowledge of magic squares, a subject that he had made his special hobby; but he soon discovered that he had never really touched more than the fringe of the subject, and that the wily Chinee could beat him easily. I present a little problem that one learned mandarin propounded to our traveller, as depicted on the last page.

The Chinaman, after remarking that the construction of the ordinary magic square of twenty-five cells is "too velly muchee easy," asked our countryman so to place the numbers `1` to `25` in the square that every column, every row, and each of the two diagonals should add up `65`, with only prime numbers on the shaded "T." Of course the prime numbers available are `1, 2, 3, 5, 7, 11, 13, 17, 19`, and `23`, so you are at liberty to select any nine of these that will serve your purpose. Can you construct this curious little magic square?

Sources:- Amusements in Mathematics, Henry Ernest Dudeney Question 410

-

THE MAGIC KNIGHT'S TOUR

Here is a problem that has never yet been solved, nor has its impossibility been demonstrated. Play the knight once to every square of the chessboard in a complete tour, numbering the squares in the order visited, so that when completed the square shall be "magic," adding up to `260` in every column, every row, and each of the two long diagonals. I shall give the best answer that I have been able to obtain, in which there is a slight error in the diagonals alone. Can a perfect solution be found? I am convinced that it cannot, but it is only a "pious opinion."

Sources:Topics:Logic Combinatorics -> Number Tables Combinatorics -> Combinatorial Geometry -> Grid Paper Geometry / Lattice Geometry- Amusements in Mathematics, Henry Ernest Dudeney Question 412

-

A CHESSBOARD FALLACY

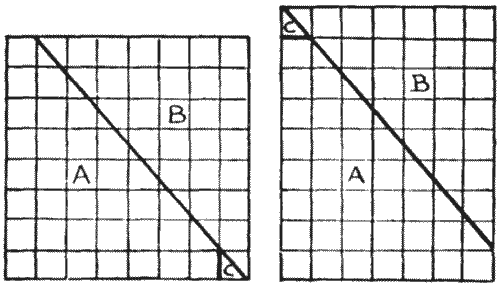

"Here is a diagram of a chessboard," he said. "You see there are sixty-four squares—eight by eight. Now I draw a straight line from the top left-hand corner, where the first and second squares meet, to the bottom right-hand corner. I cut along this line with the scissors, slide up the piece that I have marked B, and then clip off the little corner C by a cut along the first upright line. This little piece will exactly fit into its place at the top, and we now have an oblong with seven squares on one side and nine squares on the other. There are, therefore, now only sixty-three squares, because seven multiplied by nine makes sixty-three. Where on earth does that lost square go to? I have tried over and over again to catch the little beggar, but he always eludes me. For the life of me I cannot discover where he hides himself."

"It seems to be like the other old chessboard fallacy, and perhaps the explanation is the same," said Reginald—"that the pieces do not exactly fit."

"But they do fit," said Uncle John. "Try it, and you will see."

Later in the evening Reginald and George, were seen in a corner with their heads together, trying to catch that elusive little square, and it is only fair to record that before they retired for the night they succeeded in securing their prey, though some others of the company failed to see it when captured. Can the reader solve the little mystery?

Sources:Topics:Geometry -> Plane Geometry Geometry -> Area Calculation Combinatorics -> Combinatorial Geometry -> Cut a Shape / Dissection Problems- Amusements in Mathematics, Henry Ernest Dudeney Question 413

-

THE TIRING IRONS

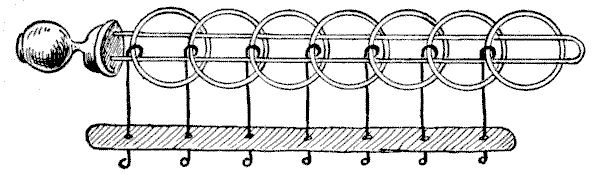

The illustration represents one of the most ancient of all mechanical puzzles. Its origin is unknown. Cardan, the mathematician, wrote about it in `1550`, and Wallis in `1693`; while it is said still to be found in obscure English villages (sometimes deposited in strange places, such as a church belfry), made of iron, and appropriately called "tiring-irons," and to be used by the Norwegians to-day as a lock for boxes and bags. In the toyshops it is sometimes called the "Chinese rings," though there seems to be no authority for the description, and it more frequently goes by the unsatisfactory name of "the puzzling rings." The French call it "Baguenaudier."

The puzzle will be seen to consist of a simple loop of wire fixed in a handle to be held in the left hand, and a certain number of rings secured by wires which pass through holes in the bar and are kept there by their blunted ends. The wires work freely in the bar, but cannot come apart from it, nor can the wires be removed from the rings. The general puzzle is to detach the loop completely from all the rings, and then to put them all on again.

Now, it will be seen at a glance that the first ring (to the right) can be taken off at any time by sliding it over the end and dropping it through the loop; or it may be put on by reversing the operation. With this exception, the only ring that can ever be removed is the one that happens to be a contiguous second on the loop at the right-hand end. Thus, with all the rings on, the second can be dropped at once; with the first ring down, you cannot drop the second, but may remove the third; with the first three rings down, you cannot drop the fourth, but may remove the fifth; and so on. It will be found that the first and second rings can be dropped together or put on together; but to prevent confusion we will throughout disallow this exceptional double move, and say that only one ring may be put on or removed at a time.

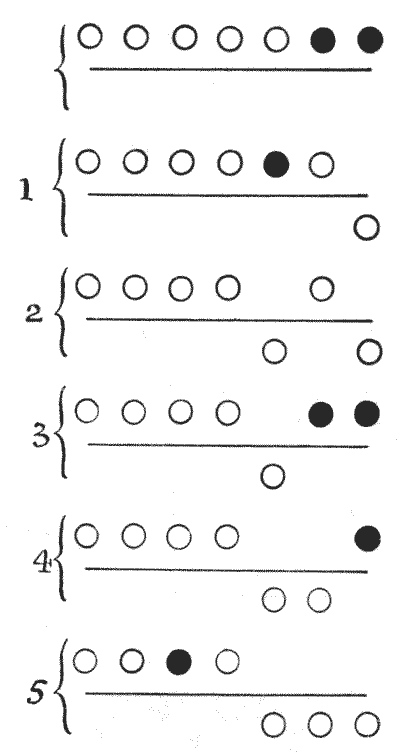

We can thus take off one ring in `1` move; two rings in `2` moves; three rings in `5` moves; four rings in `10` moves; five rings in `21` moves; and if we keep on doubling (and adding one where the number of rings is odd) we may easily ascertain the number of moves for completely removing any number of rings. To get off all the seven rings requires `85` moves. Let us look at the five moves made in removing the first three rings, the circles above the line standing for rings on the loop and those under for rings off the loop.

Drop the first ring; drop the third; put up the first; drop the second; and drop the first—`5` moves, as shown clearly in the diagrams. The dark circles show at each stage, from the starting position to the finish, which rings it is possible to drop. After move `2` it will be noticed that no ring can be dropped until one has been put on, because the first and second rings from the right now on the loop are not together. After the fifth move, if we wish to remove all seven rings we must now drop the fifth. But before we can then remove the fourth it is necessary to put on the first three and remove the first two. We shall then have `7, 6, 4, 3` on the loop, and may therefore drop the fourth. When we have put on `2` and `1` and removed `3, 2, 1`, we may drop the seventh ring. The next operation then will be to get `6, 5, 4, 3, 2, 1` on the loop and remove `4, 3, 2, 1`, when `6` will come off; then get `5, 4, 3, 2, 1` on the loop, and remove `3, 2, 1`, when `5` will come off; then get `4, 3, 2, 1` on the loop and remove `2, 1`, when `4` will come off; then get `3, 2, 1` on the loop and remove `1`, when `3` will come off; then get `2, 1` on the loop, when `2` will come off; and `1` will fall through on the 85th move, leaving the loop quite free. The reader should now be able to understand the puzzle, whether or not he has it in his hand in a practical form.

The particular problem I propose is simply this. Suppose there are altogether fourteen rings on the tiring-irons, and we proceed to take them all off in the correct way so as not to waste any moves. What will be the position of the rings after the `9`,999th move has been made?

Sources:Topics:Arithmetic Number Theory -> Division -> Parity (Even/Odd) Algebra -> Sequences -> Recurrence Relations Combinatorics -> Case Analysis / Checking Cases -> Processes / Procedures Combinatorics -> Case Analysis / Checking Cases -> Processes / Procedures- Amusements in Mathematics, Henry Ernest Dudeney Question 417

-

THE HYMN-BOARD POSER

The worthy vicar of Chumpley St. Winifred is in great distress. A little church difficulty has arisen that all the combined intelligence of the parish seems unable to surmount. What this difficulty is I will state hereafter, but it may add to the interest of the problem if I first give a short account of the curious position that has been brought about. It all has to do with the church hymn-boards, the plates of which have become so damaged that they have ceased to fulfil the purpose for which they were devised. A generous parishioner has promised to pay for a new set of plates at a certain rate of cost; but strange as it may seem, no agreement can be come to as to what that cost should be. The proposed maker of the plates has named a price which the donor declares to be absurd. The good vicar thinks they are both wrong, so he asks the schoolmaster to work out the little sum. But this individual declares that he can find no rule bearing on the subject in any of his arithmetic books. An application having been made to the local medical practitioner, as a man of more than average intellect at Chumpley, he has assured the vicar that his practice is so heavy that he has not had time even to look at it, though his assistant whispers that the doctor has been sitting up unusually late for several nights past. Widow Wilson has a smart son, who is reputed to have once won a prize for puzzle-solving. He asserts that as he cannot find any solution to the problem it must have something to do with the squaring of the circle, the duplication of the cube, or the trisection of an angle; at any rate, he has never before seen a puzzle on the principle, and he gives it up.

This was the state of affairs when the assistant curate (who, I should say, had frankly confessed from the first that a profound study of theology had knocked out of his head all the knowledge of mathematics he ever possessed) kindly sent me the puzzle.

A church has three hymn-boards, each to indicate the numbers of five different hymns to be sung at a service. All the boards are in use at the same service. The hymn-book contains `700` hymns. A new set of numbers is required, and a kind parishioner offers to present a set painted on metal plates, but stipulates that only the smallest number of plates necessary shall be purchased. The cost of each plate is to be `6`d., and for the painting of each plate the charges are to be: For one plate, `1`s.; for two plates alike, `11`¾d. each; for three plates alike, `11`½d. each, and so on, the charge being one farthing less per plate for each similarly painted plate. Now, what should be the lowest cost?

Readers will note that they are required to use every legitimate and practical method of economy. The illustration will make clear the nature of the three hymn-boards and plates. The five hymns are here indicated by means of twelve plates. These plates slide in separately at the back, and in the illustration there is room, of course, for three more plates.

Sources:Topics:Arithmetic Algebra -> Word Problems Combinatorics -> Case Analysis / Checking Cases -> Processes / Procedures- Amusements in Mathematics, Henry Ernest Dudeney Question 426