Combinatorics

Combinatorics is the art of counting. It deals with selections, arrangements, and combinations of objects. Questions involve determining the number of ways to perform tasks, arrange items (permutations), or choose subsets (combinations), often using principles like the product rule and sum rule.

Pigeonhole Principle Double Counting Binomial Coefficients and Pascal's Triangle Product Rule / Rule of Product Graph Theory Matchings Induction (Mathematical Induction) Game Theory Combinatorial Geometry Invariants Case Analysis / Checking Cases Processes / Procedures Number Tables Colorings-

A PROBLEM IN MOSAICS

The art of producing pictures or designs by means of joining together pieces of hard substances, either naturally or artificially coloured, is of very great antiquity. It was certainly known in the time of the Pharaohs, and we find a reference in the Book of Esther to "a pavement of red, and blue, and white, and black marble." Some of this ancient work that has come down to us, especially some of the Roman mosaics, would seem to show clearly, even where design is not at first evident, that much thought was bestowed upon apparently disorderly arrangements. Where, for example, the work has been produced with a very limited number of colours, there are evidences of great ingenuity in preventing the same tints coming in close proximity. Lady readers who are familiar with the construction of patchwork quilts will know how desirable it is sometimes, when they are limited in the choice of material, to prevent pieces of the same stuff coming too near together. Now, this puzzle will apply equally to patchwork quilts or tesselated pavements.

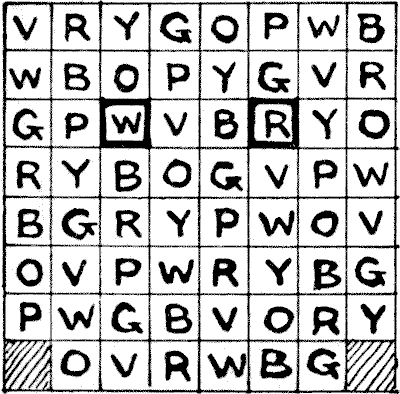

It will be seen from the diagram how a square piece of flooring may be paved with sixty-two square tiles of the eight colours violet, red, yellow, green, orange, purple, white, and blue (indicated by the initial letters), so that no tile is in line with a similarly coloured tile, vertically, horizontally, or diagonally. Sixty-four such tiles could not possibly be placed under these conditions, but the two shaded squares happen to be occupied by iron ventilators.

The puzzle is this. These two ventilators have to be removed to the positions indicated by the darkly bordered tiles, and two tiles placed in those bottom corner squares. Can you readjust the thirty-two tiles so that no two of the same colour shall still be in line?

Sources:- Amusements in Mathematics, Henry Ernest Dudeney Question 302

-

UNDER THE VEIL

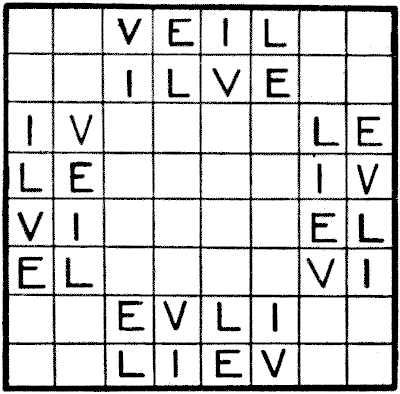

If the reader will examine the above diagram, he will see that I have so placed eight V's, eight E's, eight I's, and eight L's in the diagram that no letter is in line with a similar one horizontally, vertically, or diagonally. Thus, no V is in line with another V, no E with another E, and so on. There are a great many different ways of arranging the letters under this condition. The puzzle is to find an arrangement that produces the greatest possible number of four-letter words, reading upwards and downwards, backwards and forwards, or diagonally. All repetitions count as different words, and the five variations that may be used are: VEIL, VILE, LEVI, LIVE, and EVIL.

This will be made perfectly clear when I say that the above arrangement scores eight, because the top and bottom row both give VEIL; the second and seventh columns both give VEIL; and the two diagonals, starting from the L in the 5th row and E in the 8th row, both give LIVE and EVIL. There are therefore eight different readings of the words in all.

This difficult word puzzle is given as an example of the use of chessboard analysis in solving such things. Only a person who is familiar with the "Eight Queens" problem could hope to solve it.

Sources:Topics:Combinatorics -> Case Analysis / Checking Cases -> Processes / Procedures Combinatorics -> Colorings -> Chessboard Coloring Puzzles and Rebuses- Amusements in Mathematics, Henry Ernest Dudeney Question 303

-

BACHET'S SQUARE

One of the oldest card puzzles is by Claude Caspar Bachet de Méziriac, first published, I believe, in the `1624` edition of his work. Rearrange the sixteen court cards (including the aces) in a square so that in no row of four cards, horizontal, vertical, or diagonal, shall be found two cards of the same suit or the same value. This in itself is easy enough, but a point of the puzzle is to find in how many different ways this may be done. The eminent French mathematician A. Labosne, in his modern edition of Bachet, gives the answer incorrectly. And yet the puzzle is really quite easy. Any arrangement produces seven more by turning the square round and reflecting it in a mirror. These are counted as different by Bachet.

Note "row of four cards," so that the only diagonals we have here to consider are the two long ones.

Sources:- Amusements in Mathematics, Henry Ernest Dudeney Question 304

-

THE THIRTY-SIX LETTER BLOCKS

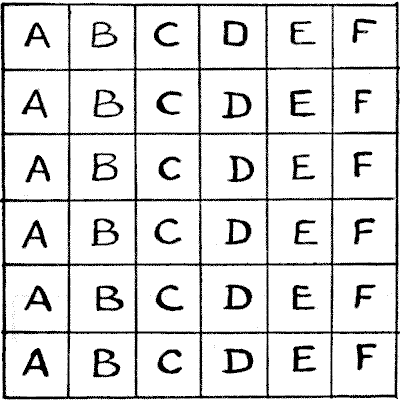

The illustration represents a box containing thirty-six letter-blocks. The puzzle is to rearrange these blocks so that no A shall be in a line vertically, horizontally, or diagonally with another A, no B with another B, no C with another C, and so on. You will find it impossible to get all the letters into the box under these conditions, but the point is to place as many as possible. Of course no letters other than those shown may be used.

Sources:Topics:Combinatorics -> Pigeonhole Principle Logic -> Reasoning / Logic Combinatorics -> Case Analysis / Checking Cases -> Processes / Procedures

The illustration represents a box containing thirty-six letter-blocks. The puzzle is to rearrange these blocks so that no A shall be in a line vertically, horizontally, or diagonally with another A, no B with another B, no C with another C, and so on. You will find it impossible to get all the letters into the box under these conditions, but the point is to place as many as possible. Of course no letters other than those shown may be used.

Sources:Topics:Combinatorics -> Pigeonhole Principle Logic -> Reasoning / Logic Combinatorics -> Case Analysis / Checking Cases -> Processes / Procedures- Amusements in Mathematics, Henry Ernest Dudeney Question 305

-

THE CROWDED CHESSBOARD

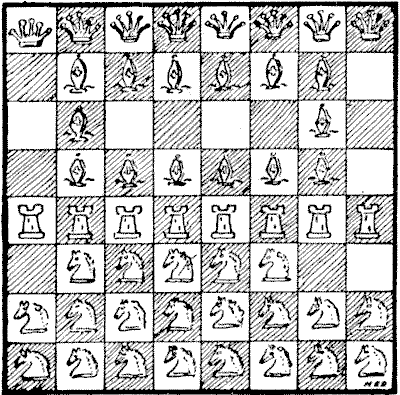

The puzzle is to rearrange the fifty-one pieces on the chessboard so that no queen shall attack another queen, no rook attack another rook, no bishop attack another bishop, and no knight attack another knight. No notice is to be taken of the intervention of pieces of another type from that under consideration—that is, two queens will be considered to attack one another although there may be, say, a rook, a bishop, and a knight between them. And so with the rooks and bishops. It is not difficult to dispose of each type of piece separately; the difficulty comes in when you have to find room for all the arrangements on the board simultaneously.

Sources:Topics:Combinatorics -> Pigeonhole Principle Combinatorics -> Case Analysis / Checking Cases -> Processes / Procedures

The puzzle is to rearrange the fifty-one pieces on the chessboard so that no queen shall attack another queen, no rook attack another rook, no bishop attack another bishop, and no knight attack another knight. No notice is to be taken of the intervention of pieces of another type from that under consideration—that is, two queens will be considered to attack one another although there may be, say, a rook, a bishop, and a knight between them. And so with the rooks and bishops. It is not difficult to dispose of each type of piece separately; the difficulty comes in when you have to find room for all the arrangements on the board simultaneously.

Sources:Topics:Combinatorics -> Pigeonhole Principle Combinatorics -> Case Analysis / Checking Cases -> Processes / Procedures- Amusements in Mathematics, Henry Ernest Dudeney Question 306

-

THE COLOURED COUNTERS

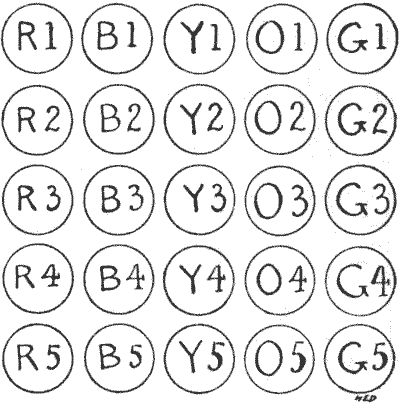

The diagram represents twenty-five coloured counters, Red, Blue, Yellow, Orange, and Green (indicated by their initials), and there are five of each colour, numbered `1, 2, 3, 4`, and `5`. The problem is so to place them in a square that neither colour nor number shall be found repeated in any one of the five rows, five columns, and two diagonals. Can you so rearrange them?

Sources:

The diagram represents twenty-five coloured counters, Red, Blue, Yellow, Orange, and Green (indicated by their initials), and there are five of each colour, numbered `1, 2, 3, 4`, and `5`. The problem is so to place them in a square that neither colour nor number shall be found repeated in any one of the five rows, five columns, and two diagonals. Can you so rearrange them?

Sources:

- Amusements in Mathematics, Henry Ernest Dudeney Question 307

-

THE GENTLE ART OF STAMP-LICKING

The Insurance Act is a most prolific source of entertaining puzzles, particularly entertaining if you happen to be among the exempt. One's initiation into the gentle art of stamp-licking suggests the following little poser: If you have a card divided into sixteen spaces (`4` × `4`), and are provided with plenty of stamps of the values `1`d., `2`d., `3`d., `4`d., and `5`d., what is the greatest value that you can stick on the card if the Chancellor of the Exchequer forbids you to place any stamp in a straight line (that is, horizontally, vertically, or diagonally) with another stamp of similar value? Of course, only one stamp can be affixed in a space. The reader will probably find, when he sees the solution, that, like the stamps themselves, he is licked He will most likely be twopence short of the maximum. A friend asked the Post Office how it was to be done; but they sent him to the Customs and Excise officer, who sent him to the Insurance Commissioners, who sent him to an approved society, who profanely sent him—but no matter. Sources:- Amusements in Mathematics, Henry Ernest Dudeney Question 308

-

THE FORTY-NINE COUNTERS

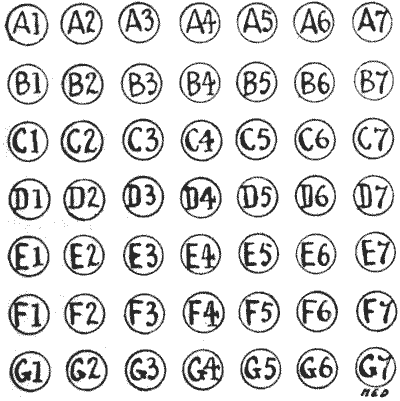

Can you rearrange the above forty-nine counters in a square so that no letter, and also no number, shall be in line with a similar one, vertically, horizontally, or diagonally? Here I, of course, mean in the lines parallel with the diagonals, in the chessboard sense.

Sources:

Can you rearrange the above forty-nine counters in a square so that no letter, and also no number, shall be in line with a similar one, vertically, horizontally, or diagonally? Here I, of course, mean in the lines parallel with the diagonals, in the chessboard sense.

Sources:

- Amusements in Mathematics, Henry Ernest Dudeney Question 309

-

THE THREE SHEEP

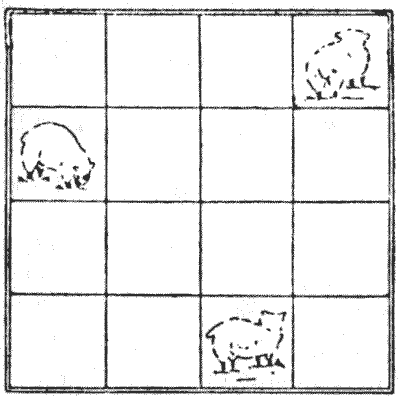

A farmer had three sheep and an arrangement of sixteen pens, divided off by hurdles in the manner indicated in the illustration. In how many different ways could he place those sheep, each in a separate pen, so that every pen should be either occupied or in line (horizontally, vertically, or diagonally) with at least one sheep? I have given one arrangement that fulfils the conditions. How many others can you find? Mere reversals and reflections must not be counted as different. The reader may regard the sheep as queens. The problem is then to place the three queens so that every square shall be either occupied or attacked by at least one queen—in the maximum number of different ways.

Sources:

A farmer had three sheep and an arrangement of sixteen pens, divided off by hurdles in the manner indicated in the illustration. In how many different ways could he place those sheep, each in a separate pen, so that every pen should be either occupied or in line (horizontally, vertically, or diagonally) with at least one sheep? I have given one arrangement that fulfils the conditions. How many others can you find? Mere reversals and reflections must not be counted as different. The reader may regard the sheep as queens. The problem is then to place the three queens so that every square shall be either occupied or attacked by at least one queen—in the maximum number of different ways.

Sources:

- Amusements in Mathematics, Henry Ernest Dudeney Question 310

-

THE FIVE DOGS PUZZLE

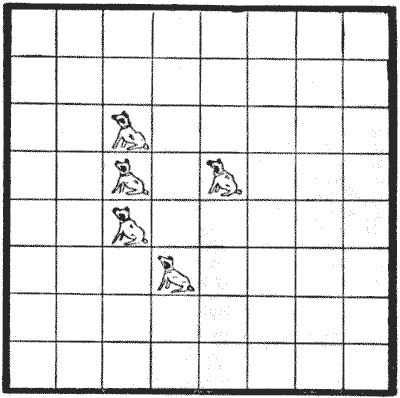

In `1863`, C.F. de Jaenisch first discussed the "Five Queens Puzzle"—to place five queens on the chessboard so that every square shall be attacked or occupied—which was propounded by his friend, a "Mr. de R." Jaenisch showed that if no queen may attack another there are ninety-one different ways of placing the five queens, reversals and reflections not counting as different. If the queens may attack one another, I have recorded hundreds of ways, but it is not practicable to enumerate them exactly. The illustration is supposed to represent an arrangement of sixty-four kennels. It will be seen that five kennels each contain a dog, and on further examination it will be seen that every one of the sixty-four kennels is in a straight line with at least one dog—either horizontally, vertically, or diagonally. Take any kennel you like, and you will find that you can draw a straight line to a dog in one or other of the three ways mentioned. The puzzle is to replace the five dogs and discover in just how many different ways they may be placed in five kennels in a straight row, so that every kennel shall always be in line with at least one dog. Reversals and reflections are here counted as different.

Sources:

The illustration is supposed to represent an arrangement of sixty-four kennels. It will be seen that five kennels each contain a dog, and on further examination it will be seen that every one of the sixty-four kennels is in a straight line with at least one dog—either horizontally, vertically, or diagonally. Take any kennel you like, and you will find that you can draw a straight line to a dog in one or other of the three ways mentioned. The puzzle is to replace the five dogs and discover in just how many different ways they may be placed in five kennels in a straight row, so that every kennel shall always be in line with at least one dog. Reversals and reflections are here counted as different.

Sources:

- Amusements in Mathematics, Henry Ernest Dudeney Question 311