Algebra

Algebra is a broad branch of mathematics that uses symbols (usually letters) to represent numbers and to state rules and relationships. It involves manipulating expressions, solving equations and inequalities, and studying functions and structures. Questions cover a wide range of these topics.

Algebraic Techniques Equations Inequalities Word Problems Sequences-

THE SPANISH DUNGEON

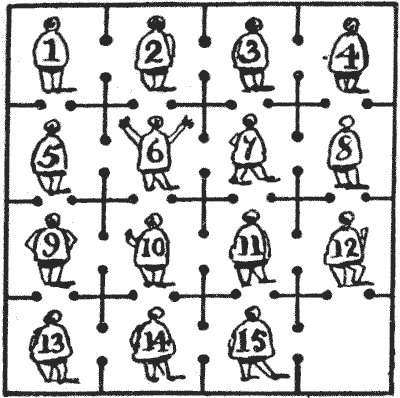

Not fifty miles from Cadiz stood in the middle ages a castle, all traces of which have for centuries disappeared. Among other interesting features, this castle contained a particularly unpleasant dungeon divided into sixteen cells, all communicating with one another, as shown in the illustration.

Now, the governor was a merry wight, and very fond of puzzles withal. One day he went to the dungeon and said to the prisoners, "By my halidame!" (or its equivalent in Spanish) "you shall all be set free if you can solve this puzzle. You must so arrange yourselves in the sixteen cells that the numbers on your backs shall form a magic square in which every column, every row, and each of the two diagonals shall add up the same. Only remember this: that in no case may two of you ever be together in the same cell."

One of the prisoners, after working at the problem for two or three days, with a piece of chalk, undertook to obtain the liberty of himself and his fellow-prisoners if they would follow his directions and move through the doorway from cell to cell in the order in which he should call out their numbers.

He succeeded in his attempt, and, what is more remarkable, it would seem from the account of his method recorded in the ancient manuscript lying before me, that he did so in the fewest possible moves. The reader is asked to show what these moves were.

Sources:Topics:Logic -> Reasoning / Logic Combinatorics -> Case Analysis / Checking Cases -> Processes / Procedures Combinatorics -> Number Tables Algebra -> Word Problems -> Solving Word Problems "From the End" / Working Backwards Puzzles and Rebuses -> Reconstruct the Exercise / Cryptarithmetic- Amusements in Mathematics, Henry Ernest Dudeney Question 403

-

THE TIRING IRONS

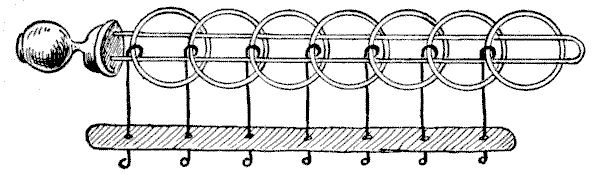

The illustration represents one of the most ancient of all mechanical puzzles. Its origin is unknown. Cardan, the mathematician, wrote about it in `1550`, and Wallis in `1693`; while it is said still to be found in obscure English villages (sometimes deposited in strange places, such as a church belfry), made of iron, and appropriately called "tiring-irons," and to be used by the Norwegians to-day as a lock for boxes and bags. In the toyshops it is sometimes called the "Chinese rings," though there seems to be no authority for the description, and it more frequently goes by the unsatisfactory name of "the puzzling rings." The French call it "Baguenaudier."

The puzzle will be seen to consist of a simple loop of wire fixed in a handle to be held in the left hand, and a certain number of rings secured by wires which pass through holes in the bar and are kept there by their blunted ends. The wires work freely in the bar, but cannot come apart from it, nor can the wires be removed from the rings. The general puzzle is to detach the loop completely from all the rings, and then to put them all on again.

Now, it will be seen at a glance that the first ring (to the right) can be taken off at any time by sliding it over the end and dropping it through the loop; or it may be put on by reversing the operation. With this exception, the only ring that can ever be removed is the one that happens to be a contiguous second on the loop at the right-hand end. Thus, with all the rings on, the second can be dropped at once; with the first ring down, you cannot drop the second, but may remove the third; with the first three rings down, you cannot drop the fourth, but may remove the fifth; and so on. It will be found that the first and second rings can be dropped together or put on together; but to prevent confusion we will throughout disallow this exceptional double move, and say that only one ring may be put on or removed at a time.

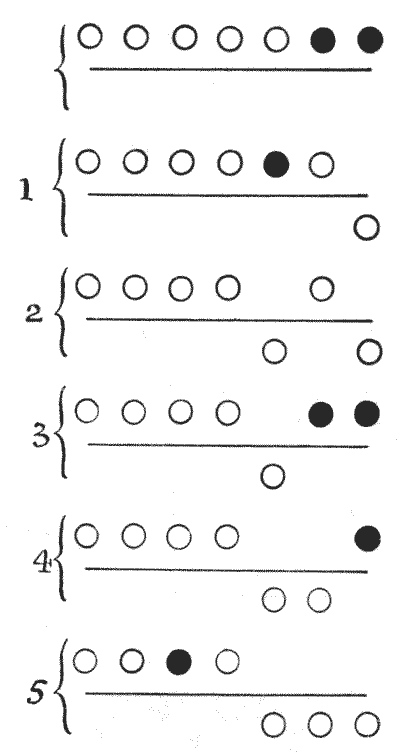

We can thus take off one ring in `1` move; two rings in `2` moves; three rings in `5` moves; four rings in `10` moves; five rings in `21` moves; and if we keep on doubling (and adding one where the number of rings is odd) we may easily ascertain the number of moves for completely removing any number of rings. To get off all the seven rings requires `85` moves. Let us look at the five moves made in removing the first three rings, the circles above the line standing for rings on the loop and those under for rings off the loop.

Drop the first ring; drop the third; put up the first; drop the second; and drop the first—`5` moves, as shown clearly in the diagrams. The dark circles show at each stage, from the starting position to the finish, which rings it is possible to drop. After move `2` it will be noticed that no ring can be dropped until one has been put on, because the first and second rings from the right now on the loop are not together. After the fifth move, if we wish to remove all seven rings we must now drop the fifth. But before we can then remove the fourth it is necessary to put on the first three and remove the first two. We shall then have `7, 6, 4, 3` on the loop, and may therefore drop the fourth. When we have put on `2` and `1` and removed `3, 2, 1`, we may drop the seventh ring. The next operation then will be to get `6, 5, 4, 3, 2, 1` on the loop and remove `4, 3, 2, 1`, when `6` will come off; then get `5, 4, 3, 2, 1` on the loop, and remove `3, 2, 1`, when `5` will come off; then get `4, 3, 2, 1` on the loop and remove `2, 1`, when `4` will come off; then get `3, 2, 1` on the loop and remove `1`, when `3` will come off; then get `2, 1` on the loop, when `2` will come off; and `1` will fall through on the 85th move, leaving the loop quite free. The reader should now be able to understand the puzzle, whether or not he has it in his hand in a practical form.

The particular problem I propose is simply this. Suppose there are altogether fourteen rings on the tiring-irons, and we proceed to take them all off in the correct way so as not to waste any moves. What will be the position of the rings after the `9`,999th move has been made?

Sources:Topics:Arithmetic Number Theory -> Division -> Parity (Even/Odd) Algebra -> Sequences -> Recurrence Relations Combinatorics -> Case Analysis / Checking Cases -> Processes / Procedures Combinatorics -> Case Analysis / Checking Cases -> Processes / Procedures- Amusements in Mathematics, Henry Ernest Dudeney Question 417

-

SUCH A GETTING UPSTAIRS

In a suburban villa there is a small staircase with eight steps, not counting the landing. The little puzzle with which Tommy Smart perplexed his family is this. You are required to start from the bottom and land twice on the floor above (stopping there at the finish), having returned once to the ground floor. But you must be careful to use every tread the same number of times. In how few steps can you make the ascent? It seems a very simple matter, but it is more than likely that at your first attempt you will make a great many more steps than are necessary. Of course you must not go more than one riser at a time.

Tommy knows the trick, and has shown it to his father, who professes to have a contempt for such things; but when the children are in bed the pater will often take friends out into the hall and enjoy a good laugh at their bewilderment. And yet it is all so very simple when you know how it is done.

Sources:- Amusements in Mathematics, Henry Ernest Dudeney Question 418

-

THE INDUSTRIOUS BOOKWORM

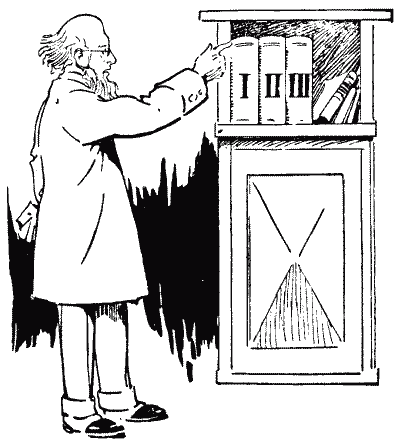

Our friend Professor Rackbrane is seen in the illustration to be propounding another of his little posers. He is explaining that since he last had occasion to take down those three volumes of a learned book from their place on his shelves a bookworm has actually bored a hole straight through from the first page to the last. He says that the leaves are together three inches thick in each volume, and that every cover is exactly one-eighth of an inch thick, and he asks how long a tunnel had the industrious worm to bore in preparing his new tube railway. Can you tell him?

Sources:Topics:Algebra -> Word Problems

Our friend Professor Rackbrane is seen in the illustration to be propounding another of his little posers. He is explaining that since he last had occasion to take down those three volumes of a learned book from their place on his shelves a bookworm has actually bored a hole straight through from the first page to the last. He says that the leaves are together three inches thick in each volume, and that every cover is exactly one-eighth of an inch thick, and he asks how long a tunnel had the industrious worm to bore in preparing his new tube railway. Can you tell him?

Sources:Topics:Algebra -> Word Problems- Amusements in Mathematics, Henry Ernest Dudeney Question 420

-

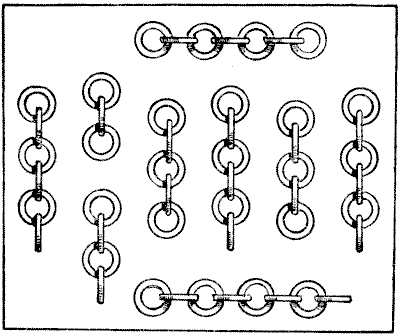

A CHAIN PUZZLE

This is a puzzle based on a pretty little idea first dealt with by the late Mr. Sam Loyd. A man had nine pieces of chain, as shown in the illustration. He wanted to join these fifty links into one endless chain. It will cost a penny to open any link and twopence to weld a link together again, but he could buy a new endless chain of the same character and quality for `2`s. `2`d. What was the cheapest course for him to adopt? Unless the reader is cunning he may find himself a good way out in his answer.

Sources:

This is a puzzle based on a pretty little idea first dealt with by the late Mr. Sam Loyd. A man had nine pieces of chain, as shown in the illustration. He wanted to join these fifty links into one endless chain. It will cost a penny to open any link and twopence to weld a link together again, but he could buy a new endless chain of the same character and quality for `2`s. `2`d. What was the cheapest course for him to adopt? Unless the reader is cunning he may find himself a good way out in his answer.

Sources:

- Amusements in Mathematics, Henry Ernest Dudeney Question 421

-

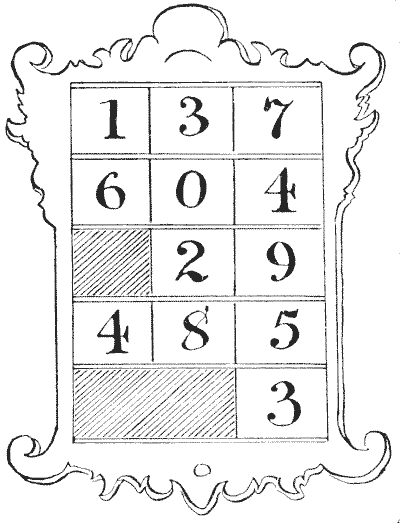

THE HYMN-BOARD POSER

The worthy vicar of Chumpley St. Winifred is in great distress. A little church difficulty has arisen that all the combined intelligence of the parish seems unable to surmount. What this difficulty is I will state hereafter, but it may add to the interest of the problem if I first give a short account of the curious position that has been brought about. It all has to do with the church hymn-boards, the plates of which have become so damaged that they have ceased to fulfil the purpose for which they were devised. A generous parishioner has promised to pay for a new set of plates at a certain rate of cost; but strange as it may seem, no agreement can be come to as to what that cost should be. The proposed maker of the plates has named a price which the donor declares to be absurd. The good vicar thinks they are both wrong, so he asks the schoolmaster to work out the little sum. But this individual declares that he can find no rule bearing on the subject in any of his arithmetic books. An application having been made to the local medical practitioner, as a man of more than average intellect at Chumpley, he has assured the vicar that his practice is so heavy that he has not had time even to look at it, though his assistant whispers that the doctor has been sitting up unusually late for several nights past. Widow Wilson has a smart son, who is reputed to have once won a prize for puzzle-solving. He asserts that as he cannot find any solution to the problem it must have something to do with the squaring of the circle, the duplication of the cube, or the trisection of an angle; at any rate, he has never before seen a puzzle on the principle, and he gives it up.

This was the state of affairs when the assistant curate (who, I should say, had frankly confessed from the first that a profound study of theology had knocked out of his head all the knowledge of mathematics he ever possessed) kindly sent me the puzzle.

A church has three hymn-boards, each to indicate the numbers of five different hymns to be sung at a service. All the boards are in use at the same service. The hymn-book contains `700` hymns. A new set of numbers is required, and a kind parishioner offers to present a set painted on metal plates, but stipulates that only the smallest number of plates necessary shall be purchased. The cost of each plate is to be `6`d., and for the painting of each plate the charges are to be: For one plate, `1`s.; for two plates alike, `11`¾d. each; for three plates alike, `11`½d. each, and so on, the charge being one farthing less per plate for each similarly painted plate. Now, what should be the lowest cost?

Readers will note that they are required to use every legitimate and practical method of economy. The illustration will make clear the nature of the three hymn-boards and plates. The five hymns are here indicated by means of twelve plates. These plates slide in separately at the back, and in the illustration there is room, of course, for three more plates.

Sources:Topics:Arithmetic Algebra -> Word Problems Combinatorics -> Case Analysis / Checking Cases -> Processes / Procedures- Amusements in Mathematics, Henry Ernest Dudeney Question 426

-

PHEASANT-SHOOTING

A Cockney friend, who is very apt to draw the long bow, and is evidently less of a sportsman than he pretends to be, relates to me the following not very credible yarn:—

"I've just been pheasant-shooting with my friend the duke. We had splendid sport, and I made some wonderful shots. What do you think of this, for instance? Perhaps you can twist it into a puzzle. The duke and I were crossing a field when suddenly twenty-four pheasants rose on the wing right in front of us. I fired, and two-thirds of them dropped dead at my feet. Then the duke had a shot at what were left, and brought down three-twenty-fourths of them, wounded in the wing. Now, out of those twenty-four birds, how many still remained?"

It seems a simple enough question, but can the reader give a correct answer?

Sources:- Amusements in Mathematics, Henry Ernest Dudeney Question 427

-

THE GARDENER AND THE COOK

A correspondent, signing himself "Simple Simon," suggested that I should give a special catch puzzle in the issue of The Weekly Dispatch for All Fools' Day, `1900`. So I gave the following, and it caused considerable amusement; for out of a very large body of competitors, many quite expert, not a single person solved it, though it ran for nearly a month.

"The illustration is a fancy sketch of my correspondent, 'Simple Simon,' in the act of trying to solve the following innocent little arithmetical puzzle. A race between a man and a woman that I happened to witness one All Fools' Day has fixed itself indelibly on my memory. It happened at a country-house, where the gardener and the cook decided to run a race to a point `100` feet straight away and return. I found that the gardener ran `3` feet at every bound and the cook only `2` feet, but then she made three bounds to his two. Now, what was the result of the race?"

A fortnight after publication I added the following note: "It has been suggested that perhaps there is a catch in the 'return,' but there is not. The race is to a point `100` feet away and home again—that is, a distance of `200` feet. One correspondent asks whether they take exactly the same time in turning, to which I reply that they do. Another seems to suspect that it is really a conundrum, and that the answer is that 'the result of the race was a (matrimonial) tie.' But I had no such intention. The puzzle is an arithmetical one, as it purports to be."

Sources:Topics:Arithmetic Algebra -> Word Problems Logic -> Reasoning / Logic Combinatorics -> Case Analysis / Checking Cases -> Processes / Procedures- Amusements in Mathematics, Henry Ernest Dudeney Question 428