Amusements in Mathematics, Henry Ernest Dudeney

-

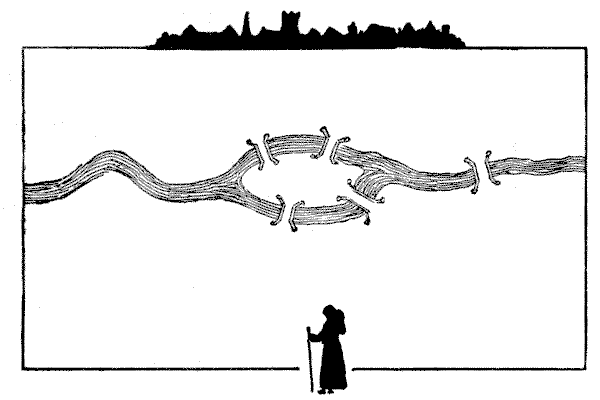

Question 261 - THE MONK AND THE BRIDGES

In this case I give a rough plan of a river with an island and five bridges. On one side of the river is a monastery, and on the other side is seen a monk in the foreground. Now, the monk has decided that he will cross every bridge once, and only once, on his return to the monastery. This is, of course, quite easy to do, but on the way he thought to himself, "I wonder how many different routes there are from which I might have selected." Could you have told him? That is the puzzle. Take your pencil and trace out a route that will take you once over all the five bridges. Then trace out a second route, then a third, and see if you can count all the variations. You will find that the difficulty is twofold: you have to avoid dropping routes on the one hand and counting the same routes more than once on the other.

Topics:Combinatorics -> Graph Theory

Topics:Combinatorics -> Graph Theory -

Question 262 - THOSE FIFTEEN SHEEP

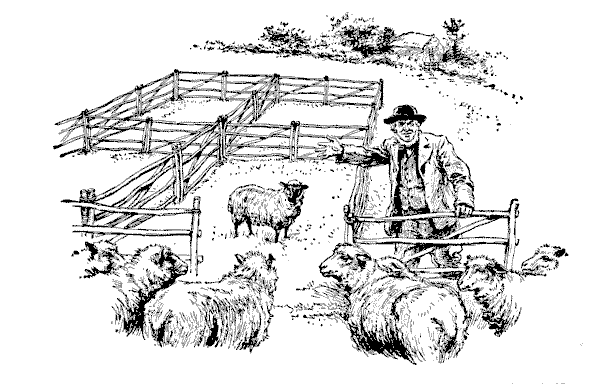

A certain cyclopædia has the following curious problem, I am told: "Place fifteen sheep in four pens so that there shall be the same number of sheep in each pen." No answer whatever is vouchsafed, so I thought I would investigate the matter. I saw that in dealing with apples or bricks the thing would appear to be quite impossible, since four times any number must be an even number, while fifteen is an odd number. I thought, therefore, that there must be some quality peculiar to the sheep that was not generally known. So I decided to interview some farmers on the subject. The first one pointed out that if we put one pen inside another, like the rings of a target, and placed all sheep in the smallest pen, it would be all right. But I objected to this, because you admittedly place all the sheep in one pen, not in four pens. The second man said that if I placed four sheep in each of three pens and three sheep in the last pen (that is fifteen sheep in all), and one of the ewes in the last pen had a lamb during the night, there would be the same number in each pen in the morning. This also failed to satisfy me. The third farmer said, "I've got four hurdle pens down in one of my fields, and a small flock of wethers, so if you will just step down with me I will show you how it is done." The illustration depicts my friend as he is about to demonstrate the matter to me. His lucid explanation was evidently that which was in the mind of the writer of the article in the cyclopædia. What was it? Can you place those fifteen sheep?

The third farmer said, "I've got four hurdle pens down in one of my fields, and a small flock of wethers, so if you will just step down with me I will show you how it is done." The illustration depicts my friend as he is about to demonstrate the matter to me. His lucid explanation was evidently that which was in the mind of the writer of the article in the cyclopædia. What was it? Can you place those fifteen sheep?

-

Question 263 - KING ARTHUR'S KNIGHTS

King Arthur sat at the Round Table on three successive evenings with his knights—Beleobus, Caradoc, Driam, Eric, Floll, and Galahad—but on no occasion did any person have as his neighbour one who had before sat next to him. On the first evening they sat in alphabetical order round the table. But afterwards King Arthur arranged the two next sittings so that he might have Beleobus as near to him as possible and Galahad as far away from him as could be managed. How did he seat the knights to the best advantage, remembering that rule that no knight may have the same neighbour twice? -

Question 264 - THE CITY LUNCHEONS

Twelve men connected with a large firm in the City of London sit down to luncheon together every day in the same room. The tables are small ones that only accommodate two persons at the same time. Can you show how these twelve men may lunch together on eleven days in pairs, so that no two of them shall ever sit twice together? We will represent the men by the first twelve letters of the alphabet, and suppose the first day's pairing to be as follows—

(A B) (C D) (E F) (G H) (I J) (K L).

Then give any pairing you like for the next day, say—

(A C) (B D) (E G) (F H) (I K) (J L),

and so on, until you have completed your eleven lines, with no pair ever occurring twice. There are a good many different arrangements possible. Try to find one of them.

Topics:Combinatorics -

Question 265 - A PUZZLE FOR CARD-PLAYERS

Twelve members of a club arranged to play bridge together on eleven evenings, but no player was ever to have the same partner more than once, or the same opponent more than twice. Can you draw up a scheme showing how they may all sit down at three tables every evening? Call the twelve players by the first twelve letters of the alphabet and try to group them. -

Question 266 - A TENNIS TOURNAMENT

Four married couples played a "mixed double" tennis tournament, a man and a lady always playing against a man and a lady. But no person ever played with or against any other person more than once. Can you show how they all could have played together in the two courts on three successive days? This is a little puzzle of a quite practical kind, and it is just perplexing enough to be interesting. -

Question 267 - THE WRONG HATS

"One of the most perplexing things I have come across lately," said Mr. Wilson, "is this. Eight men had been dining not wisely but too well at a certain London restaurant. They were the last to leave, but not one man was in a condition to identify his own hat. Now, considering that they took their hats at random, what are the chances that every man took a hat that did not belong to him?"

"The first thing," said Mr. Waterson, "is to see in how many different ways the eight hats could be taken."

"That is quite easy," Mr. Stubbs explained. "Multiply together the numbers, `1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7`, and `8`. Let me see—half a minute—yes; there are `40,320` different ways."

"Now all you've got to do is to see in how many of these cases no man has his own hat," said Mr. Waterson."

Thank you, I'm not taking any," said Mr. Packhurst. "I don't envy the man who attempts the task of writing out all those forty-thousand-odd cases and then picking out the ones he wants."

They all agreed that life is not long enough for that sort of amusement; and as nobody saw any other way of getting at the answer, the matter was postponed indefinitely. Can you solve the puzzle?

-

Question 268 - THE PEAL OF BELLS

A correspondent, who is apparently much interested in campanology, asks me how he is to construct what he calls a "true and correct" peal for four bells. He says that every possible permutation of the four bells must be rung once, and once only. He adds that no bell must move more than one place at a time, that no bell must make more than two successive strokes in either the first or the last place, and that the last change must be able to pass into the first. These fantastic conditions will be found to be observed in the little peal for three bells, as follows:—

1 2 3 2 1 3 2 3 1 3 2 1 3 1 2 1 3 2 How are we to give him a correct solution for his four bells?

Topics:Combinatorics -> Product Rule / Rule of Product -

Question 269 - THREE MEN IN A BOAT

A certain generous London manufacturer gives his workmen every year a week's holiday at the seaside at his own expense. One year fifteen of his men paid a visit to Herne Bay. On the morning of their departure from London they were addressed by their employer, who expressed the hope that they would have a very pleasant time.

"I have been given to understand," he added, "that some of you fellows are very fond of rowing, so I propose on this occasion to provide you with this recreation, and at the same time give you an amusing little puzzle to solve. During the seven days that you are at Herne Bay every one of you will go out every day at the same time for a row, but there must always be three men in a boat and no more. No two men may ever go out in a boat together more than once, and no man is allowed to go out twice in the same boat. If you can manage to do this, and use as few different boats as possible, you may charge the firm with the expense."

One of the men tells me that the experience he has gained in such matters soon enabled him to work out the answer to the entire satisfaction of themselves and their employer. But the amusing part of the thing is that they never really solved the little mystery. I find their method to have been quite incorrect, and I think it will amuse my readers to discover how the men should have been placed in the boats. As their names happen to have been Andrews, Baker, Carter, Danby, Edwards, Frith, Gay, Hart, Isaacs, Jackson, Kent, Lang, Mason, Napper, and Onslow, we can call them by their initials and write out the five groups for each of the seven days in the following simple way:

1 2 3 4 5 First Day: (ABC) (DEF) (GHI) (JKL) (MNO). The men within each pair of brackets are here seen to be in the same boat, and therefore A can never go out with B or with C again, and C can never go out again with B. The same applies to the other four boats. The figures show the number on the boat, so that A, B, or C, for example, can never go out in boat No. `1` again.

Topics:Combinatorics -

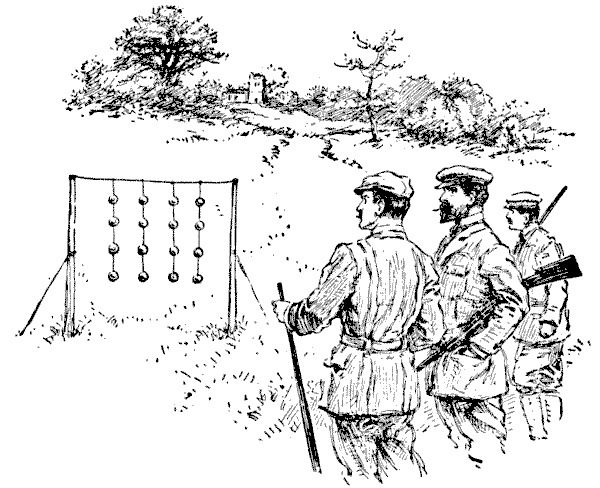

Question 270 - THE GLASS BALLS

A number of clever marksmen were staying at a country house, and the host, to provide a little amusement, suspended strings of glass balls, as shown in the illustration, to be fired at. After they had all put their skill to a sufficient test, somebody asked the following question: "What is the total number of different ways in which these sixteen balls may be broken, if we must always break the lowest ball that remains on any string?" Thus, one way would be to break all the four balls on each string in succession, taking the strings from left to right. Another would be to break all the fourth balls on the four strings first, then break the three remaining on the first string, then take the balls on the three other strings alternately from right to left, and so on. There is such a vast number of different ways (since every little variation of order makes a different way) that one is apt to be at first impressed by the great difficulty of the problem. Yet it is really quite simple when once you have hit on the proper method of attacking it. How many different ways are there? Topics:Combinatorics -> Product Rule / Rule of Product

Topics:Combinatorics -> Product Rule / Rule of Product