Amusements in Mathematics, Henry Ernest Dudeney

-

Question 281 - PAINTING A PYRAMID

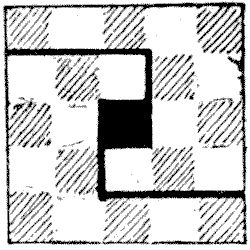

This puzzle concerns the painting of the four sides of a tetrahedron, or triangular pyramid. If you cut out a piece of cardboard of the triangular shape shown in Fig. `1`, and then cut half through along the dotted lines, it will fold up and form a perfect triangular pyramid. And I would first remind my readers that the primary colours of the solar spectrum are seven—violet, indigo, blue, green, yellow, orange, and red. When I was a child I was taught to remember these by the ungainly word formed by the initials of the colours, "Vibgyor." In how many different ways may the triangular pyramid be coloured, using in every case one, two, three, or four colours of the solar spectrum? Of course a side can only receive a single colour, and no side can be left uncoloured. But there is one point that I must make quite clear. The four sides are not to be regarded as individually distinct. That is to say, if you paint your pyramid as shown in Fig. `2` (where the bottom side is green and the other side that is out of view is yellow), and then paint another in the order shown in Fig. `3`, these are really both the same and count as one way. For if you tilt over No. `2` to the right it will so fall as to represent No. `3`. The avoidance of repetitions of this kind is the real puzzle of the thing. If a coloured pyramid cannot be placed so that it exactly resembles in its colours and their relative order another pyramid, then they are different. Remember that one way would be to colour all the four sides red, another to colour two sides green, and the remaining sides yellow and blue; and so on.

In how many different ways may the triangular pyramid be coloured, using in every case one, two, three, or four colours of the solar spectrum? Of course a side can only receive a single colour, and no side can be left uncoloured. But there is one point that I must make quite clear. The four sides are not to be regarded as individually distinct. That is to say, if you paint your pyramid as shown in Fig. `2` (where the bottom side is green and the other side that is out of view is yellow), and then paint another in the order shown in Fig. `3`, these are really both the same and count as one way. For if you tilt over No. `2` to the right it will so fall as to represent No. `3`. The avoidance of repetitions of this kind is the real puzzle of the thing. If a coloured pyramid cannot be placed so that it exactly resembles in its colours and their relative order another pyramid, then they are different. Remember that one way would be to colour all the four sides red, another to colour two sides green, and the remaining sides yellow and blue; and so on.

-

Question 282 - THE ANTIQUARY'S CHAIN

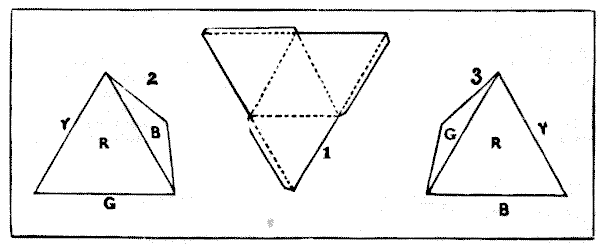

An antiquary possessed a number of curious old links, which he took to a blacksmith, and told him to join together to form one straight piece of chain, with the sole condition that the two circular links were not to be together. The following illustration shows the appearance of the chain and the form of each link. Now, supposing the owner should separate the links again, and then take them to another smith and repeat his former instructions exactly, what are the chances against the links being put together exactly as they were by the first man? Remember that every successive link can be joined on to another in one of two ways, just as you can put a ring on your finger in two ways, or link your forefingers and thumbs in two ways.

-

Question 283 - THE FIFTEEN DOMINOES

In this case we do not use the complete set of twenty-eight dominoes to be found in the ordinary box. We dispense with all those dominoes that have a five or a six on them and limit ourselves to the fifteen that remain, where the double-four is the highest.

In how many different ways may the fifteen dominoes be arranged in a straight line in accordance with the simple rule of the game that a number must always be placed against a similar number—that is, a four against a four, a blank against a blank, and so on? Left to right and right to left of the same arrangement are to be counted as two different ways.

-

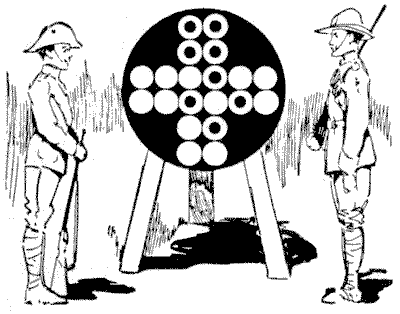

Question 284 - THE CROSS TARGET

In the illustration we have a somewhat curious target designed by an eccentric sharpshooter. His idea was that in order to score you must hit four circles in as many shots so that those four shots shall form a square. It will be seen by the results recorded on the target that two attempts have been successful. The first man hit the four circles at the top of the cross, and thus formed his square. The second man intended to hit the four in the bottom arm, but his second shot, on the left, went too high. This compelled him to complete his four in a different way than he intended. It will thus be seen that though it is immaterial which circle you hit at the first shot, the second shot may commit you to a definite procedure if you are to get your square. Now, the puzzle is to say in just how many different ways it is possible to form a square on the target with four shots.

In the illustration we have a somewhat curious target designed by an eccentric sharpshooter. His idea was that in order to score you must hit four circles in as many shots so that those four shots shall form a square. It will be seen by the results recorded on the target that two attempts have been successful. The first man hit the four circles at the top of the cross, and thus formed his square. The second man intended to hit the four in the bottom arm, but his second shot, on the left, went too high. This compelled him to complete his four in a different way than he intended. It will thus be seen that though it is immaterial which circle you hit at the first shot, the second shot may commit you to a definite procedure if you are to get your square. Now, the puzzle is to say in just how many different ways it is possible to form a square on the target with four shots.

-

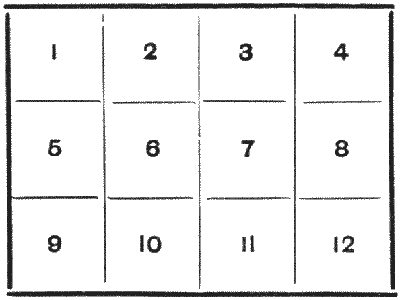

Question 285 - THE FOUR POSTAGE STAMPS

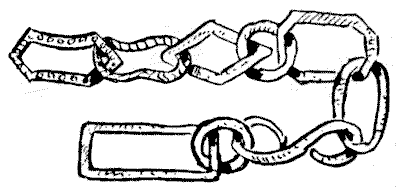

"It is as easy as counting," is an expression one sometimes hears. But mere counting may be puzzling at times. Take the following simple example. Suppose you have just bought twelve postage stamps, in this form—three by four—and a friend asks you to oblige him with four stamps, all joined together—no stamp hanging on by a mere corner. In how many different ways is it possible for you to tear off those four stamps? You see, you can give him `1, 2, 3, 4`, or `2, 3, 6, 7`, or `1, 2, 3, 6`, or `1, 2, 3, 7`, or `2, 3, 4, 8`, and so on. Can you count the number of different ways in which those four stamps might be delivered? There are not many more than fifty ways, so it is not a big count. Can you get the exact number?

"It is as easy as counting," is an expression one sometimes hears. But mere counting may be puzzling at times. Take the following simple example. Suppose you have just bought twelve postage stamps, in this form—three by four—and a friend asks you to oblige him with four stamps, all joined together—no stamp hanging on by a mere corner. In how many different ways is it possible for you to tear off those four stamps? You see, you can give him `1, 2, 3, 4`, or `2, 3, 6, 7`, or `1, 2, 3, 6`, or `1, 2, 3, 7`, or `2, 3, 4, 8`, and so on. Can you count the number of different ways in which those four stamps might be delivered? There are not many more than fifty ways, so it is not a big count. Can you get the exact number?

-

Question 286 - PAINTING THE DIE

In how many different ways may the numbers on a single die be marked, with the only condition that the `1` and `6`, the `2` and `5`, and the `3` and `4` must be on opposite sides? It is a simple enough question, and yet it will puzzle a good many people.Topics:Combinatorics -

Question 287 - AN ACROSTIC PUZZLE

In the making or solving of double acrostics, has it ever occurred to you to consider the variety and limitation of the pair of initial and final letters available for cross words? You may have to find a word beginning with A and ending with B, or A and C, or A and D, and so on. Some combinations are obviously impossible—such, for example, as those with Q at the end. But let us assume that a good English word can be found for every case. Then how many possible pairs of letters are available?

Topics:Combinatorics -

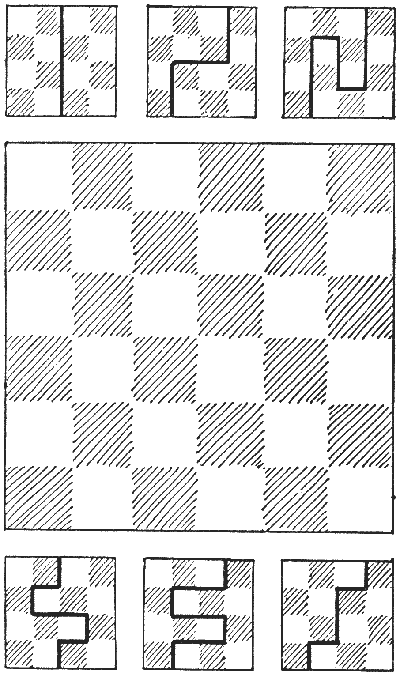

Question 288 - CHEQUERED BOARD DIVISIONS

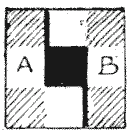

I recently asked myself the question: In how many different ways may a chessboard be divided into two parts of the same size and shape by cuts along the lines dividing the squares? The problem soon proved to be both fascinating and bristling with difficulties. I present it in a simplified form, taking a board of smaller dimensions. It is obvious that a board of four squares can only be so divided in one way—by a straight cut down the centre—because we shall not count reversals and reflections as different. In the case of a board of sixteen squares—four by four—there are just six different ways. I have given all these in the diagram, and the reader will not find any others. Now, take the larger board of thirty-six squares, and try to discover in how many ways it may be cut into two parts of the same size and shape.

It is obvious that a board of four squares can only be so divided in one way—by a straight cut down the centre—because we shall not count reversals and reflections as different. In the case of a board of sixteen squares—four by four—there are just six different ways. I have given all these in the diagram, and the reader will not find any others. Now, take the larger board of thirty-six squares, and try to discover in how many ways it may be cut into two parts of the same size and shape.

-

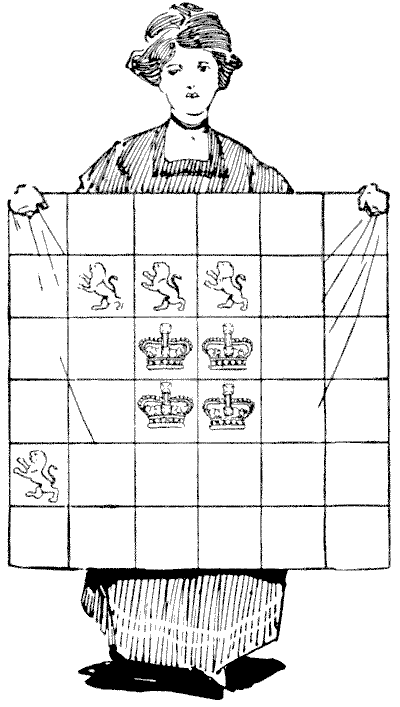

Question 289 - LIONS AND CROWNS

The young lady in the illustration is confronted with a little cutting-out difficulty in which the reader may be glad to assist her. She wishes, for some reason that she has not communicated to me, to cut that square piece of valuable material into four parts, all of exactly the same size and shape, but it is important that every piece shall contain a lion and a crown. As she insists that the cuts can only be made along the lines dividing the squares, she is considerably perplexed to find out how it is to be done. Can you show her the way? There is only one possible method of cutting the stuff.

-

Question 290 - BOARDS WITH AN ODD NUMBER OF SQUARES

We will here consider the question of those boards that contain an odd number of squares. We will suppose that the central square is first cut out, so as to leave an even number of squares for division. Now, it is obvious that a square three by three can only be divided in one way, as shown in Fig. `1`. It will be seen that the pieces A and B are of the same size and shape, and that any other way of cutting would only produce the same shaped pieces, so remember that these variations are not counted as different ways. The puzzle I propose is to cut the board five by five (Fig. `2`) into two pieces of the same size and shape in as many different ways as possible. I have shown in the illustration one way of doing it. How many different ways are there altogether? A piece which when turned over resembles another piece is not considered to be of a different shape.