Amusements in Mathematics, Henry Ernest Dudeney

-

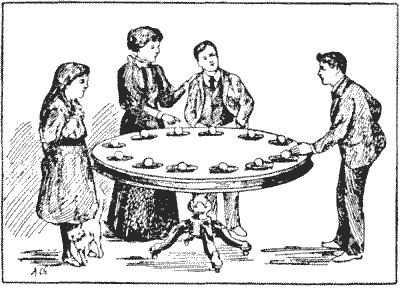

Question 231 - PLATES AND COINS

Place twelve plates, as shown, on a round table, with a penny or orange in every plate. Start from any plate you like and, always going in one direction round the table, take up one penny, pass it over two other pennies, and place it in the next plate. Go on again; take up another penny and, having passed it over two pennies, place it in a plate; and so continue your journey. Six coins only are to be removed, and when these have been placed there should be two coins in each of six plates and six plates empty. An important point of the puzzle is to go round the table as few times as possible. It does not matter whether the two coins passed over are in one or two plates, nor how many empty plates you pass a coin over. But you must always go in one direction round the table and end at the point from which you set out. Your hand, that is to say, goes steadily forward in one direction, without ever moving backwards. Topics:Puzzles and Rebuses

Topics:Puzzles and Rebuses -

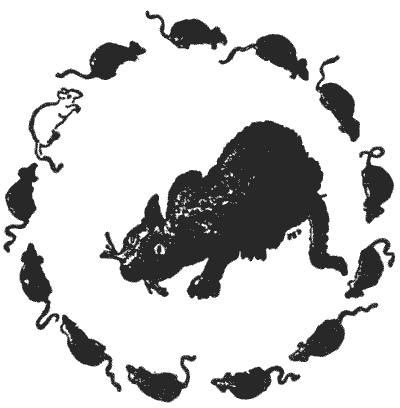

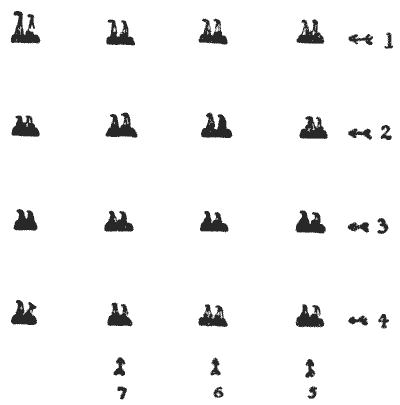

Question 232 - CATCHING THE MICE

"Play fair!" said the mice. "You know the rules of the game."

"Yes, I know the rules," said the cat. "I've got to go round and round the circle, in the direction that you are looking, and eat every thirteenth mouse, but I must keep the white mouse for a tit-bit at the finish. Thirteen is an unlucky number, but I will do my best to oblige you."

"Hurry up, then!" shouted the mice.

"Give a fellow time to think," said the cat. "I don't know which of you to start at. I must figure it out.

"While the cat was working out the puzzle he fell asleep, and, the spell being thus broken, the mice returned home in safety. At which mouse should the cat have started the count in order that the white mouse should be the last eaten?

When the reader has solved that little puzzle, here is a second one for him. What is the smallest number that the cat can count round and round the circle, if he must start at the white mouse (calling that "one" in the count) and still eat the white mouse last of all?

And as a third puzzle try to discover what is the smallest number that the cat can count round and round if she must start at the white mouse (calling that "one") and make the white mouse the third eaten.

-

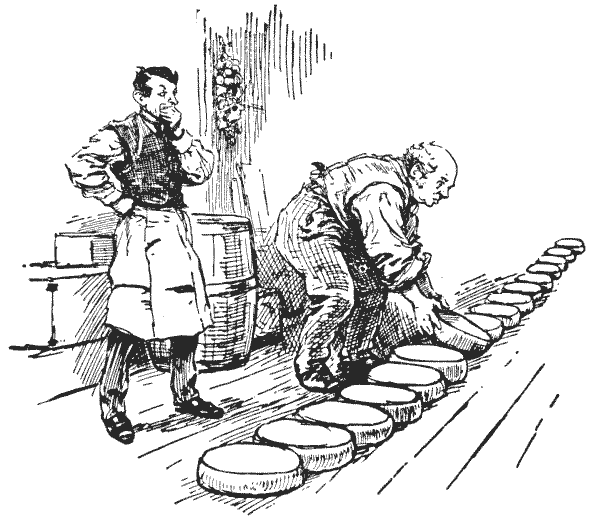

Question 233 - THE ECCENTRIC CHEESEMONGER

The cheesemonger depicted in the illustration is an inveterate puzzle lover. One of his favourite puzzles is the piling of cheeses in his warehouse, an amusement that he finds good exercise for the body as well as for the mind. He places sixteen cheeses on the floor in a straight row and then makes them into four piles, with four cheeses in every pile, by always passing a cheese over four others. If you use sixteen counters and number them in order from `1` to `16`, then you may place `1` on `6, 11` on `1, 7` on `4`, and so on, until there are four in every pile. It will be seen that it does not matter whether the four passed over are standing alone or piled; they count just the same, and you can always carry a cheese in either direction. There are a great many different ways of doing it in twelve moves, so it makes a good game of "patience" to try to solve it so that the four piles shall be left in different stipulated places. For example, try to leave the piles at the extreme ends of the row, on Nos. `1, 2, 15` and `16`; this is quite easy. Then try to leave three piles together, on Nos. `13, 14`, and `15`. Then again play so that they shall be left on Nos. `3, 5, 12`, and `14`.

Topics:Puzzles and Rebuses

The cheesemonger depicted in the illustration is an inveterate puzzle lover. One of his favourite puzzles is the piling of cheeses in his warehouse, an amusement that he finds good exercise for the body as well as for the mind. He places sixteen cheeses on the floor in a straight row and then makes them into four piles, with four cheeses in every pile, by always passing a cheese over four others. If you use sixteen counters and number them in order from `1` to `16`, then you may place `1` on `6, 11` on `1, 7` on `4`, and so on, until there are four in every pile. It will be seen that it does not matter whether the four passed over are standing alone or piled; they count just the same, and you can always carry a cheese in either direction. There are a great many different ways of doing it in twelve moves, so it makes a good game of "patience" to try to solve it so that the four piles shall be left in different stipulated places. For example, try to leave the piles at the extreme ends of the row, on Nos. `1, 2, 15` and `16`; this is quite easy. Then try to leave three piles together, on Nos. `13, 14`, and `15`. Then again play so that they shall be left on Nos. `3, 5, 12`, and `14`.

Topics:Puzzles and Rebuses -

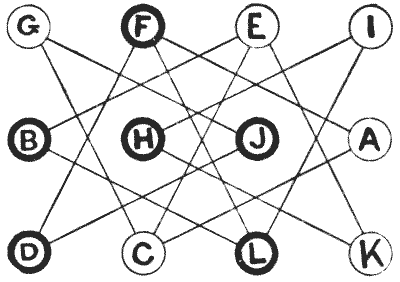

Question 234 - THE EXCHANGE PUZZLE

Here is a rather entertaining little puzzle with moving counters. You only need twelve counters—six of one colour, marked A, C, E, G, I, and K, and the other six marked B, D, F, H, J, and L. You first place them on the diagram, as shown in the illustration, and the puzzle is to get them into regular alphabetical order, as follows:—

A B C D E F G H I J K L The moves are made by exchanges of opposite colours standing on the same line. Thus, G and J may exchange places, or F and A, but you cannot exchange G and C, or F and D, because in one case they are both white and in the other case both black. Can you bring about the required arrangement in seventeen exchanges?

It cannot be done in fewer moves. The puzzle is really much easier than it looks, if properly attacked.

-

Question 235 - TORPEDO PRACTICE

If a fleet of sixteen men-of-war were lying at anchor and surrounded by the enemy, how many ships might be sunk if every torpedo, projected in a straight line, passed under three vessels and sank the fourth? In the diagram we have arranged the fleet in square formation, where it will be seen that as many as seven ships may be sunk (those in the top row and first column) by firing the torpedoes indicated by arrows. Anchoring the fleet as we like, to what extent can we increase this number? Remember that each successive ship is sunk before another torpedo is launched, and that every torpedo proceeds in a different direction; otherwise, by placing the ships in a straight line, we might sink as many as thirteen! It is an interesting little study in naval warfare, and eminently practical—provided the enemy will allow you to arrange his fleet for your convenience and promise to lie still and do nothing!

If a fleet of sixteen men-of-war were lying at anchor and surrounded by the enemy, how many ships might be sunk if every torpedo, projected in a straight line, passed under three vessels and sank the fourth? In the diagram we have arranged the fleet in square formation, where it will be seen that as many as seven ships may be sunk (those in the top row and first column) by firing the torpedoes indicated by arrows. Anchoring the fleet as we like, to what extent can we increase this number? Remember that each successive ship is sunk before another torpedo is launched, and that every torpedo proceeds in a different direction; otherwise, by placing the ships in a straight line, we might sink as many as thirteen! It is an interesting little study in naval warfare, and eminently practical—provided the enemy will allow you to arrange his fleet for your convenience and promise to lie still and do nothing!

-

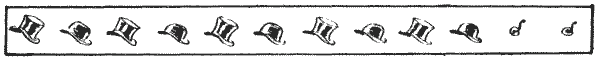

Question 236 - THE HAT PUZZLE

Ten hats were hung on pegs as shown in the illustration—five silk hats and five felt "bowlers," alternately silk and felt. The two pegs at the end of the row were empty.

The puzzle is to remove two contiguous hats to the vacant pegs, then two other adjoining hats to the pegs now unoccupied, and so on until five pairs have been moved and the hats again hang in an unbroken row, but with all the silk ones together and all the felt hats together.

Remember, the two hats removed must always be contiguous ones, and you must take one in each hand and place them on their new pegs without reversing their relative position. You are not allowed to cross your hands, nor to hang up one at a time.

Can you solve this old puzzle, which I give as introductory to the next? Try it with counters of two colours or with coins, and remember that the two empty pegs must be left at one end of the row.

Topics:Puzzles and Rebuses -

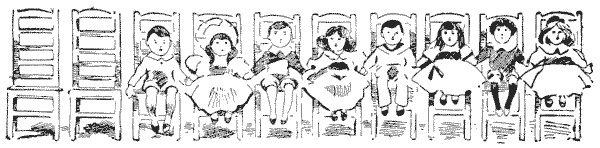

Question 237 - BOYS AND GIRLS

If you mark off ten divisions on a sheet of paper to represent the chairs, and use eight numbered counters for the children, you will have a fascinating pastime. Let the odd numbers represent boys and even numbers girls, or you can use counters of two colours, or coins.

The puzzle is to remove two children who are occupying adjoining chairs and place them in two empty chairs, making them first change sides; then remove a second pair of children from adjoining chairs and place them in the two now vacant, making them change sides; and so on, until all the boys are together and all the girls together, with the two vacant chairs at one end as at present. To solve the puzzle you must do this in five moves. The two children must always be taken from chairs that are next to one another; and remember the important point of making the two children change sides, as this latter is the distinctive feature of the puzzle. By "change sides" I simply mean that if, for example, you first move `1` and `2` to the vacant chairs, then the first (the outside) chair will be occupied by `2` and the second one by `1`.

-

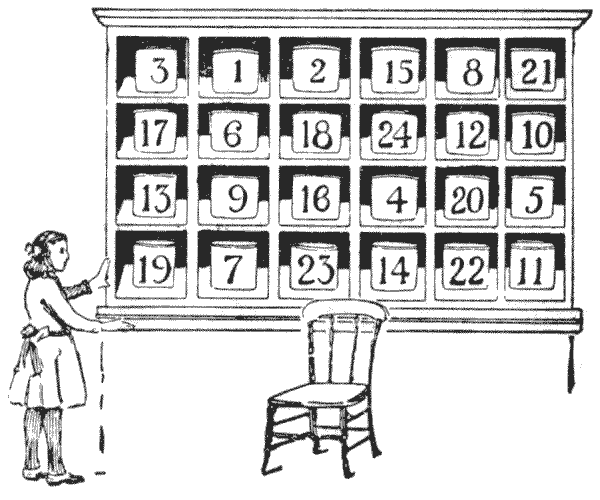

Question 238 - ARRANGING THE JAMPOTS

I happened to see a little girl sorting out some jam in a cupboard for her mother. She was putting each different kind of preserve apart on the shelves. I noticed that she took a pot of damson in one hand and a pot of gooseberry in the other and made them change places; then she changed a strawberry with a raspberry, and so on. It was interesting to observe what a lot of unnecessary trouble she gave herself by making more interchanges than there was any need for, and I thought it would work into a good puzzle.

It will be seen in the illustration that little Dorothy has to manipulate twenty-four large jampots in as many pigeon-holes. She wants to get them in correct numerical order—that is, `1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6` on the top shelf, `7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12` on the next shelf, and so on. Now, if she always takes one pot in the right hand and another in the left and makes them change places, how many of these interchanges will be necessary to get all the jampots in proper order? She would naturally first change the `1` and the `3`, then the `2` and the `3`, when she would have the first three pots in their places. How would you advise her to go on then? Place some numbered counters on a sheet of paper divided into squares for the pigeon-holes, and you will find it an amusing puzzle.

-

Question 239 - A JUVENILE PUZZLE

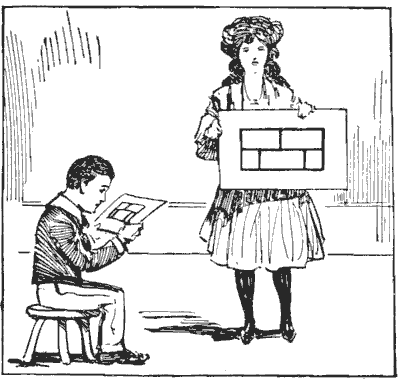

For years I have been perpetually consulted by my juvenile friends about this little puzzle. Most children seem to know it, and yet, curiously enough, they are invariably unacquainted with the answer. The question they always ask is, "Do, please, tell me whether it is really possible." I believe Houdin the conjurer used to be very fond of giving it to his child friends, but I cannot say whether he invented the little puzzle or not. No doubt a large number of my readers will be glad to have the mystery of the solution cleared up, so I make no apology for introducing this old "teaser."

The puzzle is to draw with three strokes of the pencil the diagram that the little girl is exhibiting in the illustration. Of course, you must not remove your pencil from the paper during a stroke or go over the same line a second time. You will find that you can get in a good deal of the figure with one continuous stroke, but it will always appear as if four strokes are necessary.

Another form of the puzzle is to draw the diagram on a slate and then rub it out in three rubs.

Topics:Combinatorics -> Graph Theory -

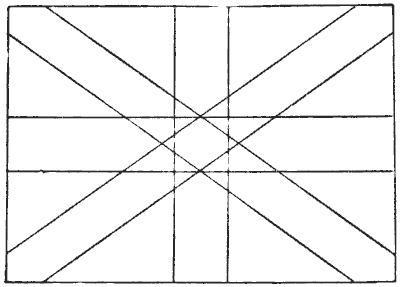

Question 240 - THE UNION JACK

The illustration is a rough sketch somewhat resembling the British flag, the Union Jack. It is not possible to draw the whole of it without lifting the pencil from the paper or going over the same line twice. The puzzle is to find out just how much of the drawing it is possible to make without lifting your pencil or going twice over the same line. Take your pencil and see what is the best you can do.

Topics:Combinatorics -> Graph Theory

The illustration is a rough sketch somewhat resembling the British flag, the Union Jack. It is not possible to draw the whole of it without lifting the pencil from the paper or going over the same line twice. The puzzle is to find out just how much of the drawing it is possible to make without lifting your pencil or going twice over the same line. Take your pencil and see what is the best you can do.

Topics:Combinatorics -> Graph Theory