Amusements in Mathematics, Henry Ernest Dudeney

-

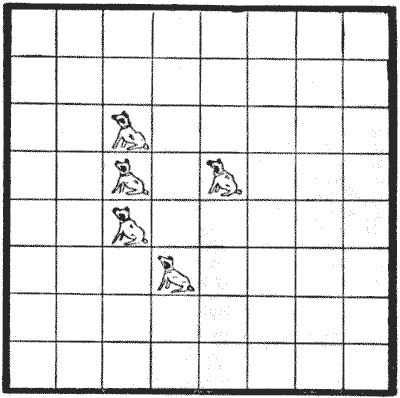

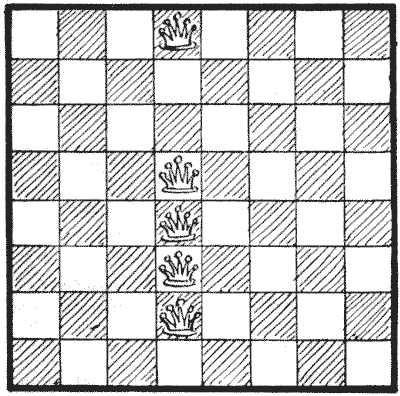

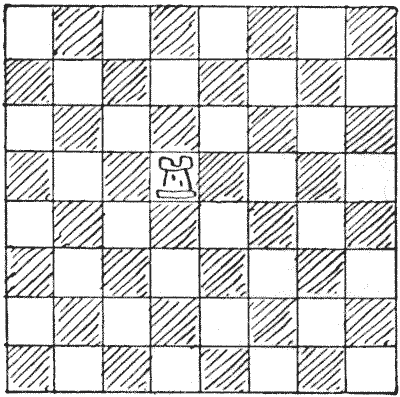

Question 311 - THE FIVE DOGS PUZZLE

In `1863`, C.F. de Jaenisch first discussed the "Five Queens Puzzle"—to place five queens on the chessboard so that every square shall be attacked or occupied—which was propounded by his friend, a "Mr. de R." Jaenisch showed that if no queen may attack another there are ninety-one different ways of placing the five queens, reversals and reflections not counting as different. If the queens may attack one another, I have recorded hundreds of ways, but it is not practicable to enumerate them exactly. The illustration is supposed to represent an arrangement of sixty-four kennels. It will be seen that five kennels each contain a dog, and on further examination it will be seen that every one of the sixty-four kennels is in a straight line with at least one dog—either horizontally, vertically, or diagonally. Take any kennel you like, and you will find that you can draw a straight line to a dog in one or other of the three ways mentioned. The puzzle is to replace the five dogs and discover in just how many different ways they may be placed in five kennels in a straight row, so that every kennel shall always be in line with at least one dog. Reversals and reflections are here counted as different.

The illustration is supposed to represent an arrangement of sixty-four kennels. It will be seen that five kennels each contain a dog, and on further examination it will be seen that every one of the sixty-four kennels is in a straight line with at least one dog—either horizontally, vertically, or diagonally. Take any kennel you like, and you will find that you can draw a straight line to a dog in one or other of the three ways mentioned. The puzzle is to replace the five dogs and discover in just how many different ways they may be placed in five kennels in a straight row, so that every kennel shall always be in line with at least one dog. Reversals and reflections are here counted as different.

-

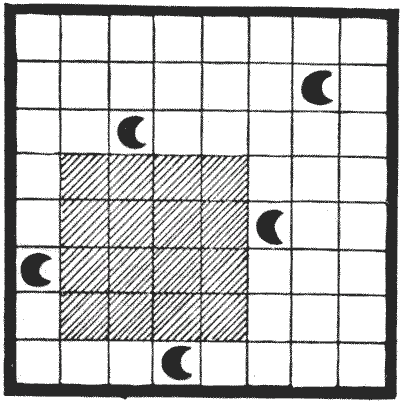

Question 312 - THE FIVE CRESCENTS OF BYZANTIUM

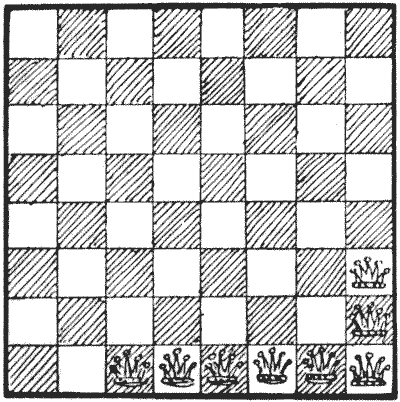

When Philip of Macedon, the father of Alexander the Great, found himself confronted with great difficulties in the siege of Byzantium, he set his men to undermine the walls. His desires, however, miscarried, for no sooner had the operations been begun than a crescent moon suddenly appeared in the heavens and discovered his plans to his adversaries. The Byzantines were naturally elated, and in order to show their gratitude they erected a statue to Diana, and the crescent became thenceforward a symbol of the state. In the temple that contained the statue was a square pavement composed of sixty-four large and costly tiles. These were all plain, with the exception of five, which bore the symbol of the crescent. These five were for occult reasons so placed that every tile should be watched over by (that is, in a straight line, vertically, horizontally, or diagonally with) at least one of the crescents. The arrangement adopted by the Byzantine architect was as follows:—

Now, to cover up one of these five crescents was a capital offence, the death being something very painful and lingering. But on a certain occasion of festivity it was necessary to lay down on this pavement a square carpet of the largest dimensions possible, and I have shown in the illustration by dark shading the largest dimensions that would be available.

The puzzle is to show how the architect, if he had foreseen this question of the carpet, might have so arranged his five crescent tiles in accordance with the required conditions, and yet have allowed for the largest possible square carpet to be laid down without any one of the five crescent tiles being covered, or any portion of them.

-

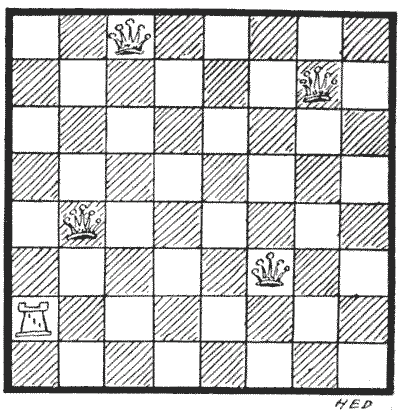

Question 313 - QUEENS AND BISHOP PUZZLE

It will be seen that every square of the board is either occupied or attacked. The puzzle is to substitute a bishop for the rook on the same square, and then place the four queens on other squares so that every square shall again be either occupied or attacked.

-

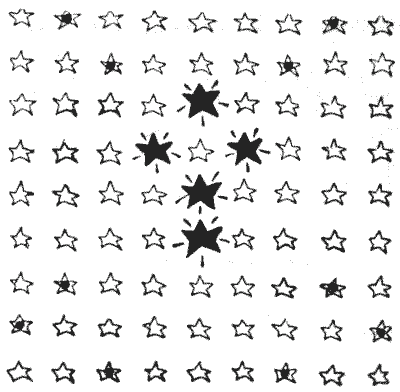

Question 314 - THE SOUTHERN CROSS

In the above illustration we have five Planets and eighty-one Fixed Stars, five of the latter being hidden by the Planets. It will be found that every Star, with the exception of the ten that have a black spot in their centres, is in a straight line, vertically, horizontally, or diagonally, with at least one of the Planets. The puzzle is so to rearrange the Planets that all the Stars shall be in line with one or more of them.

In rearranging the Planets, each of the five may be moved once in a straight line, in either of the three directions mentioned. They will, of course, obscure five other Stars in place of those at present covered.

-

Question 315 - THE HAT-PEG PUZZLE

Here is a five-queen puzzle that I gave in a fanciful dress in `1897`. As the queens were there represented as hats on sixty-four pegs, I will keep to the title, "The Hat-Peg Puzzle." It will be seen that every square is occupied or attacked. The puzzle is to remove one queen to a different square so that still every square is occupied or attacked, then move a second queen under a similar condition, then a third queen, and finally a fourth queen. After the fourth move every square must be attacked or occupied, but no queen must then attack another. Of course, the moves need not be "queen moves;" you can move a queen to any part of the board.

to a different square so that still every square is occupied or attacked, then move a second queen under a similar condition, then a third queen, and finally a fourth queen. After the fourth move every square must be attacked or occupied, but no queen must then attack another. Of course, the moves need not be "queen moves;" you can move a queen to any part of the board.

-

Question 316 - THE AMAZONS

This puzzle is based on one by Captain Turton. Remove three of the queens to other squares so that there shall be eleven squares on the board that are not attacked. The removal of the three queens need not be by "queen moves." You may take them up and place them anywhere. There is only one solution.

Topics:Puzzles and Rebuses

This puzzle is based on one by Captain Turton. Remove three of the queens to other squares so that there shall be eleven squares on the board that are not attacked. The removal of the three queens need not be by "queen moves." You may take them up and place them anywhere. There is only one solution.

Topics:Puzzles and Rebuses -

Question 317 - A PUZZLE WITH PAWNS

Place two pawns in the middle of the chessboard, one at Q `4` and the other at K `5`. Now, place the remaining fourteen pawns (sixteen in all) so that no three shall be in a straight line in any possible direction.

Note that I purposely do not say queens, because by the words "any possible direction" I go beyond attacks on diagonals. The pawns must be regarded as mere points in space—at the centres of the squares. See dotted lines in the case of No. `300`, "The Eight Queens."

-

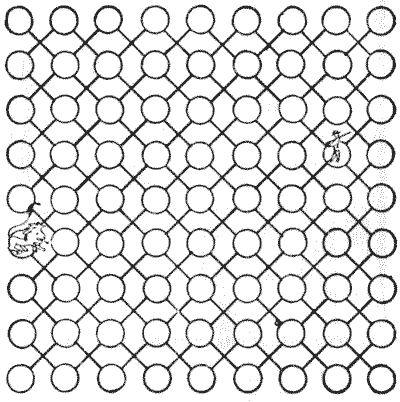

Question 318 - LION-HUNTING

My friend Captain Potham Hall, the renowned hunter of big game, says there is nothing more exhilarating than a brush with a herd—a pack—a team—a flock—a swarm (it has taken me a full quarter of an hour to recall the right word, but I have it at last)—a pride of lions. Why a number of lions are called a "pride," a number of whales a "school," and a number of foxes a "skulk" are mysteries of philology into which I will not enter.

Well, the captain says that if a spirited lion crosses your path in the desert it becomes lively, for the lion has generally been looking for the man just as much as the man has sought the king of the forest. And yet when they meet they always quarrel and fight it out. A little contemplation of this unfortunate and long-standing feud between two estimable families has led me to figure out a few calculations as to the probability of the man and the lion crossing one another's path in the jungle. In all these cases one has to start on certain more or less arbitrary assumptions. That is why in the above illustration I have thought it necessary to represent the paths in the desert with such rigid regularity. Though the captain assures me that the tracks of the lions usually run much in this way, I have doubts.

The puzzle is simply to find out in how many different ways the man and the lion may be placed on two different spots that are not on the same path. By "paths" it must be understood that I only refer to the ruled lines. Thus, with the exception of the four corner spots, each combatant is always on two paths and no more. It will be seen that there is a lot of scope for evading one another in the desert, which is just what one has always understood.

-

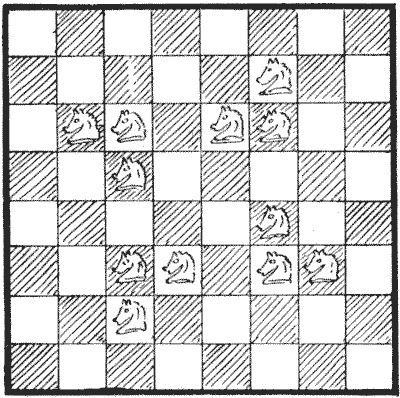

Question 319 - THE KNIGHT-GUARDS

The knight is the irresponsible low comedian of the chessboard. "He is a very uncertain, sneaking, and demoralizing rascal," says an American writer. "He can only move two squares, but makes up in the quality of his locomotion for its quantity, for he can spring one square sideways and one forward simultaneously, like a cat; can stand on one leg in the middle of the board and jump to any one of eight squares he chooses; can get on one side of a fence and blackguard three or four men on the other; has an objectionable way of inserting himself in safe places where he can scare the king and compel him to move, and then gobble a queen. For pure cussedness the knight has no equal, and when you chase him out of one hole he skips into another." Attempts have been made over and over again to obtain a short, simple, and exact definition of the move of the knight—without success. It really consists in moving one square like a rook, and then another square like a bishop—the two operations being done in one leap, so that it does not matter whether the first square passed over is occupied by another piece or not. It is, in fact, the only leaping move in chess. But difficult as it is to define, a child can learn it by inspection in a few minutes.

I have shown in the diagram how twelve knights (the fewest possible that will perform the feat) may be placed on the chessboard so that every square is either occupied or attacked by a knight. Examine every square in turn, and you will find that this is so. Now, the puzzle in this case is to discover what is the smallest possible number of knights that is required in order that every square shall be either occupied or attacked, and every knight protected by another knight. And how would you arrange them? It will be found that of the twelve shown in the diagram only four are thus protected by being a knight's move from another knight.

-

Question 320 - THE ROOK'S TOUR

The puzzle is to move the single rook over the whole board, so that it shall visit every square of the board once, and only once, and end its tour on the square from which it starts. You have to do this in as few moves as possible, and unless you are very careful you will take just one move too many. Of course, a square is regarded equally as "visited" whether you merely pass over it or make it a stopping-place, and we will not quibble over the point whether the original square is actually visited twice. We will assume that it is not.

Topics:Combinatorics -> Graph Theory

The puzzle is to move the single rook over the whole board, so that it shall visit every square of the board once, and only once, and end its tour on the square from which it starts. You have to do this in as few moves as possible, and unless you are very careful you will take just one move too many. Of course, a square is regarded equally as "visited" whether you merely pass over it or make it a stopping-place, and we will not quibble over the point whether the original square is actually visited twice. We will assume that it is not.

Topics:Combinatorics -> Graph Theory