Amusements in Mathematics, Henry Ernest Dudeney

-

Question 331 - THE SCIENTIFIC SKATER

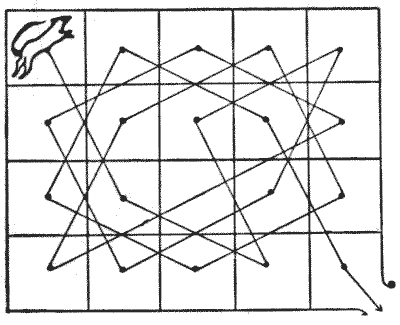

It will be seen that this skater has marked on the ice sixty-four points or stars, and he proposes to start from his present position near the corner and enter every one of the points in fourteen straight lines. How will he do it? Of course there is no objection to his passing over any point more than once, but his last straight stroke must bring him back to the position from which he started.

It is merely a matter of taking your pencil and starting from the spot on which the skater's foot is at present resting, and striking out all the stars in fourteen continuous straight lines, returning to the point from which you set out.

-

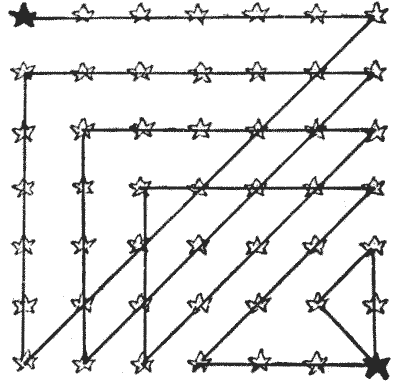

Question 332 - THE FORTY-NINE STARS

The puzzle in this case is simply to take your pencil and, starting from one black star, strike out all the stars in twelve straight strokes, ending at the other black star. It will be seen that the attempt shown in the illustration requires fifteen strokes. Can you do it in twelve? Every turning must be made on a star, and the lines must be parallel to the sides and diagonals of the square, as shown. In this case we are dealing with a chessboard of reduced dimensions, but only queen moves (without going outside the boundary as in the last case) are required.

Topics:Combinatorics -> Graph Theory

The puzzle in this case is simply to take your pencil and, starting from one black star, strike out all the stars in twelve straight strokes, ending at the other black star. It will be seen that the attempt shown in the illustration requires fifteen strokes. Can you do it in twelve? Every turning must be made on a star, and the lines must be parallel to the sides and diagonals of the square, as shown. In this case we are dealing with a chessboard of reduced dimensions, but only queen moves (without going outside the boundary as in the last case) are required.

Topics:Combinatorics -> Graph Theory -

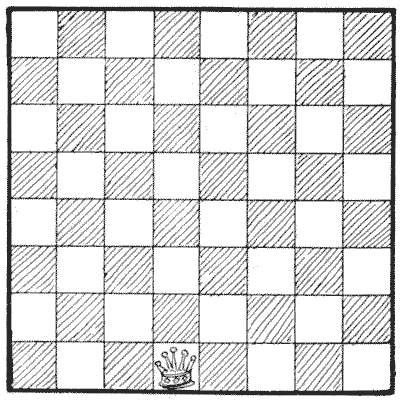

Question 333 - THE QUEEN'S JOURNEY

Place the queen on her own square, as shown in the illustration, and then try to discover the greatest distance that she can travel over the board in five queen's moves without passing over any square a second time. Mark the queen's path on the board, and note carefully also that she must never cross her own track. It seems simple enough, but the reader may find that he has tripped.

Place the queen on her own square, as shown in the illustration, and then try to discover the greatest distance that she can travel over the board in five queen's moves without passing over any square a second time. Mark the queen's path on the board, and note carefully also that she must never cross her own track. It seems simple enough, but the reader may find that he has tripped.

-

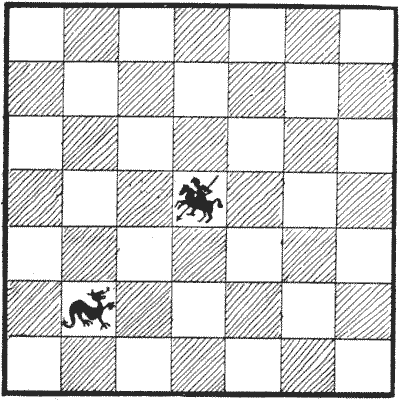

Question 334 - ST. GEORGE AND THE DRAGON

Here is a little puzzle on a reduced chessboard of forty-nine squares. St. George wishes to kill the dragon. Killing dragons was a well-known pastime of his, and, being a knight, it was only natural that he should desire to perform the feat in a series of knight's moves. Can you show how, starting from that central square, he may visit once, and only once, every square of the board in a chain of chess knight's moves, and end by capturing the dragon on his last move? Of course a variety of different ways are open to him, so try to discover a route that forms some pretty design when you have marked each successive leap by a straight line from square to square.

Here is a little puzzle on a reduced chessboard of forty-nine squares. St. George wishes to kill the dragon. Killing dragons was a well-known pastime of his, and, being a knight, it was only natural that he should desire to perform the feat in a series of knight's moves. Can you show how, starting from that central square, he may visit once, and only once, every square of the board in a chain of chess knight's moves, and end by capturing the dragon on his last move? Of course a variety of different ways are open to him, so try to discover a route that forms some pretty design when you have marked each successive leap by a straight line from square to square.

-

Question 335 - FARMER LAWRENCE'S CORNFIELDS

One of the most beautiful districts within easy distance of London for a summer ramble is that part of Buckinghamshire known as the Valley of the Chess—at least, it was a few years ago, before it was discovered by the speculative builder. At the beginning of the present century there lived, not far from Latimers, a worthy but eccentric farmer named Lawrence. One of his queer notions was that every person who lived near the banks of the river Chess ought to be in some way acquainted with the noble game of the same name, and in order to impress this fact on his men and his neighbours he adopted at times strange terminology. For example, when one of his ewes presented him with a lamb, he would say that it had "queened a pawn"; when he put up a new barn against the highway, he called it "castling on the king's side"; and when he sent a man with a gun to keep his neighbour's birds off his fields, he spoke of it as "attacking his opponent's rooks." Everybody in the neighbourhood used to be amused at Farmer Lawrence's little jokes, and one boy (the wag of the village) who got his ears pulled by the old gentleman for stealing his "chestnuts" went so far as to call him "a silly old chess-protector!"

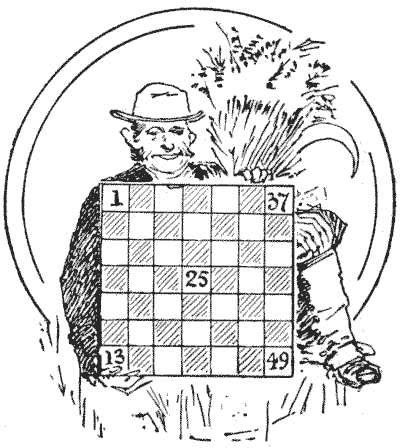

One year he had a large square field divided into forty-nine square plots, as shown in the illustration. The white squares were sown with wheat and the black squares with barley. When the harvest time came round he gave orders that his men were first to cut the corn in the patch marked `1`, and that each successive cutting should be exactly a knight's move from the last one, the thirteenth cutting being in the patch marked `13`, the twenty-fifth in the patch marked `25`, the thirty-seventh in the one marked `37`, and the last, or forty-ninth cutting, in the patch marked `49`. This was too much for poor Hodge, and each day Farmer Lawrence had to go down to the field and show which piece had to be operated upon. But the problem will perhaps present no difficulty to my readers.

-

Question 336 - THE GREYHOUND PUZZLE

In this puzzle the twenty kennels do not communicate with one another by doors, but are divided off by a low wall. The solitary occupant is the greyhound which lives in the kennel in the top left-hand corner. When he is allowed his liberty he has to obtain it by visiting every kennel once and only once in a series of knight's moves, ending at the bottom right-hand corner, which is open to the world. The lines in the above diagram show one solution. The puzzle is to discover in how many different ways the greyhound may thus make his exit from his corner kennel.

-

Question 337 - THE FOUR KANGAROOS

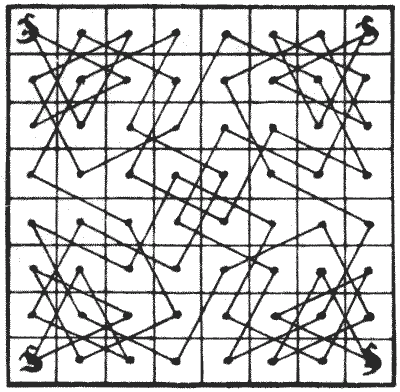

In introducing a little Commonwealth problem, I must first explain that the diagram represents the sixty-four fields, all properly fenced off from one another, of an Australian settlement, though I need hardly say that our kith and kin "down under" always do set out their land in this methodical and exact manner. It will be seen that in every one of the four corners is a kangaroo. Why kangaroos have a marked preference for corner plots has never been satisfactorily explained, and it would be out of place to discuss the point here. I should also add that kangaroos, as is well known, always leap in what we call "knight's moves." In fact, chess players would probably have adopted the better term "kangaroo's move" had not chess been invented before kangaroos.

In introducing a little Commonwealth problem, I must first explain that the diagram represents the sixty-four fields, all properly fenced off from one another, of an Australian settlement, though I need hardly say that our kith and kin "down under" always do set out their land in this methodical and exact manner. It will be seen that in every one of the four corners is a kangaroo. Why kangaroos have a marked preference for corner plots has never been satisfactorily explained, and it would be out of place to discuss the point here. I should also add that kangaroos, as is well known, always leap in what we call "knight's moves." In fact, chess players would probably have adopted the better term "kangaroo's move" had not chess been invented before kangaroos.The puzzle is simply this. One morning each kangaroo went for his morning hop, and in sixteen consecutive knight's leaps visited just fifteen different fields and jumped back to his corner. No field was visited by more than one of the kangaroos. The diagram shows how they arranged matters. What you are asked to do is to show how they might have performed the feat without any kangaroo ever crossing the horizontal line in the middle of the square that divides the board into two equal parts.

-

Question 338 - THE BOARD IN COMPARTMENTS

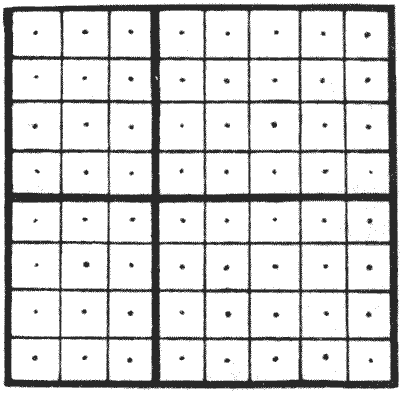

We cannot divide the ordinary chessboard into four equal square compartments, and describe a complete tour, or even path, in each compartment. But we may divide it into four compartments, as in the illustration, two containing each twenty squares, and the other two each twelve squares, and so obtain an interesting puzzle. You are asked to describe a complete re-entrant tour on this board, starting where you like, but visiting every square in each successive compartment before passing into another one, and making the final leap back to the square from which the knight set out. It is not difficult, but will be found very entertaining and not uninstructive.

Whether a re-entrant "tour" or a complete knight's "path" is possible or not on a rectangular board of given dimensions depends not only on its dimensions, but also on its shape. A tour is obviously not possible on a board containing an odd number of cells, such as `5` by `5` or `7` by `7`, for this reason: Every successive leap of the knight must be from a white square to a black and a black to a white alternately. But if there be an odd number of cells or squares there must be one more square of one colour than of the other, therefore the path must begin from a square of the colour that is in excess, and end on a similar colour, and as a knight's move from one colour to a similar colour is impossible the path cannot be re-entrant. But a perfect tour may be made on a rectangular board of any dimensions provided the number of squares be even, and that the number of squares on one side be not less than `6` and on the other not less than `5`. In other words, the smallest rectangular board on which a re-entrant tour is possible is one that is `6` by `5`.

A complete knight's path (not re-entrant) over all the squares of a board is never possible if there be only two squares on one side; nor is it possible on a square board of smaller dimensions than `5` by `5`. So that on a board `4` by `4` we can neither describe a knight's tour nor a complete knight's path; we must leave one square unvisited. Yet on a board `4` by `3` (containing four squares fewer) a complete path may be described in sixteen different ways. It may interest the reader to discover all these. Every path that starts from and ends at different squares is here counted as a different solution, and even reverse routes are called different.

-

Question 339 - THE FOUR KNIGHTS' TOURS

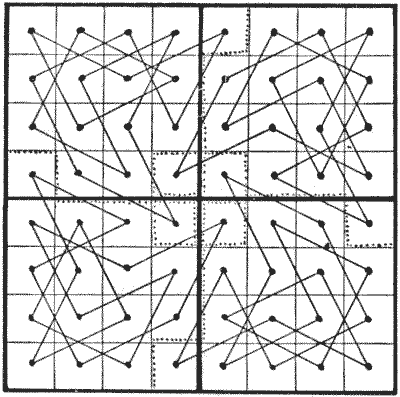

I will repeat that if a chessboard be cut into four equal parts, as indicated by the dark lines in the illustration, it is not possible to perform a knight's tour, either re-entrant or not, on one of the parts. The best re-entrant attempt is shown, in which each knight has to trespass twice on other parts. The puzzle is to cut the board differently into four parts, each of the same size and shape, so that a re-entrant knight's tour may be made on each part. Cuts along the dotted lines will not do, as the four central squares of the board would be either detached or hanging on by a mere thread.

I will repeat that if a chessboard be cut into four equal parts, as indicated by the dark lines in the illustration, it is not possible to perform a knight's tour, either re-entrant or not, on one of the parts. The best re-entrant attempt is shown, in which each knight has to trespass twice on other parts. The puzzle is to cut the board differently into four parts, each of the same size and shape, so that a re-entrant knight's tour may be made on each part. Cuts along the dotted lines will not do, as the four central squares of the board would be either detached or hanging on by a mere thread.

-

Question 340 - THE CUBIC KNIGHT'S TOUR

Some few years ago I happened to read somewhere that Abnit Vandermonde, a clever mathematician, who was born in `1736` and died in `1793`, had devoted a good deal of study to the question of knight's tours. Beyond what may be gathered from a few fragmentary references, I am not aware of the exact nature or results of his investigations, but one thing attracted my attention, and that was the statement that he had proposed the question of a tour of the knight over the six surfaces of a cube, each surface being a chessboard. Whether he obtained a solution or not I do not know, but I have never seen one published. So I at once set to work to master this interesting problem. Perhaps the reader may like to attempt it.