Amusements in Mathematics, Henry Ernest Dudeney

-

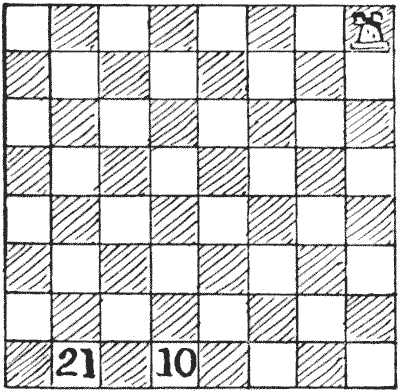

Question 321 - THE ROOK'S JOURNEY

This puzzle I call "The Rook's Journey," because the word "tour" (derived from a turner's wheel) implies that we return to the point from which we set out, and we do not do this in the present case. We should not be satisfied with a personally conducted holiday tour that ended by leaving us, say, in the middle of the Sahara. The rook here makes twenty-one moves, in the course of which journey it visits every square of the board once and only once, stopping at the square marked `10` at the end of its tenth move, and ending at the square marked `21`. Two consecutive moves cannot be made in the same direction—that is to say, you must make a turn after every move.

-

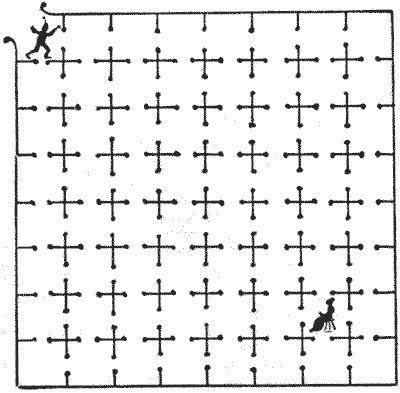

Question 322 - THE LANGUISHING MAIDEN

A wicked baron in the good old days imprisoned an innocent maiden in one of the deepest dungeons beneath the castle moat. It will be seen from our illustration that there were sixty-three cells in the dungeon, all connected by open doors, and the maiden was chained in the cell in which she is shown. Now, a valiant knight, who loved the damsel, succeeded in rescuing her from the enemy. Having gained an entrance to the dungeon at the point where he is seen, he succeeded in reaching the maiden after entering every cell once and only once. Take your pencil and try to trace out such a route. When you have succeeded, then try to discover a route in twenty-two straight paths through the cells. It can be done in this number without entering any cell a second time.

A wicked baron in the good old days imprisoned an innocent maiden in one of the deepest dungeons beneath the castle moat. It will be seen from our illustration that there were sixty-three cells in the dungeon, all connected by open doors, and the maiden was chained in the cell in which she is shown. Now, a valiant knight, who loved the damsel, succeeded in rescuing her from the enemy. Having gained an entrance to the dungeon at the point where he is seen, he succeeded in reaching the maiden after entering every cell once and only once. Take your pencil and try to trace out such a route. When you have succeeded, then try to discover a route in twenty-two straight paths through the cells. It can be done in this number without entering any cell a second time.

-

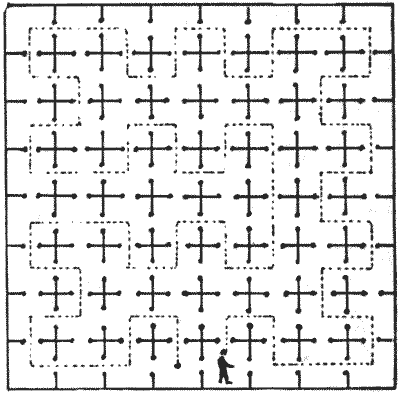

Question 323 - A DUNGEON PUZZLE

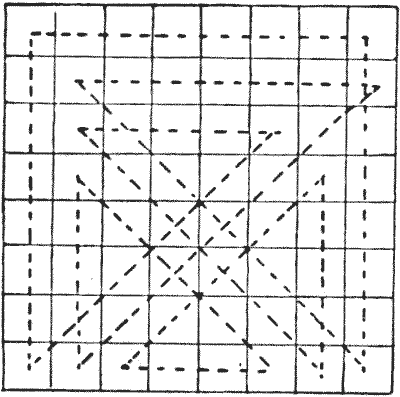

A French prisoner, for his sins (or other people's), was confined in an underground dungeon containing sixty-four cells, all communicating with open doorways, as shown in our illustration. In order to reduce the tedium of his restricted life, he set himself various puzzles, and this is one of them. Starting from the cell in which he is shown, how could he visit every cell once, and only once, and make as many turnings as possible? His first attempt is shown by the dotted track. It will be found that there are as many as fifty-five straight lines in his path, but after many attempts he improved upon this. Can you get more than fifty-five? You may end your path in any cell you like. Try the puzzle with a pencil on chessboard diagrams, or you may regard them as rooks' moves on a board.

Topics:Combinatorics -> Graph Theory

A French prisoner, for his sins (or other people's), was confined in an underground dungeon containing sixty-four cells, all communicating with open doorways, as shown in our illustration. In order to reduce the tedium of his restricted life, he set himself various puzzles, and this is one of them. Starting from the cell in which he is shown, how could he visit every cell once, and only once, and make as many turnings as possible? His first attempt is shown by the dotted track. It will be found that there are as many as fifty-five straight lines in his path, but after many attempts he improved upon this. Can you get more than fifty-five? You may end your path in any cell you like. Try the puzzle with a pencil on chessboard diagrams, or you may regard them as rooks' moves on a board.

Topics:Combinatorics -> Graph Theory -

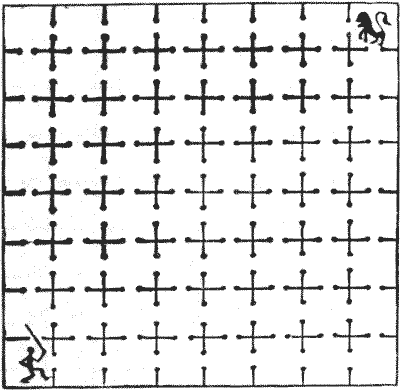

Question 324 - THE LION AND THE MAN

In a public place in Rome there once stood a prison divided into sixty-four cells, all open to the sky and all communicating with one another, as shown in the illustration. The sports that here took place were watched from a high tower. The favourite game was to place a Christian in one corner cell and a lion in the diagonally opposite corner and then leave them with all the inner doors open. The consequent effect was sometimes most laughable. On one occasion the man was given a sword. He was no coward, and was as anxious to find the lion as the lion undoubtedly was to find him. The man visited every cell once and only once in the fewest possible straight lines until he reached the lion's cell. The lion, curiously enough, also visited every cell once and only once in the fewest possible straight lines until he finally reached the man's cell. They started together and went at the same speed; yet, although they occasionally got glimpses of one another, they never once met. The puzzle is to show the route that each happened to take.

Topics:Combinatorics -> Graph Theory

The man visited every cell once and only once in the fewest possible straight lines until he reached the lion's cell. The lion, curiously enough, also visited every cell once and only once in the fewest possible straight lines until he finally reached the man's cell. They started together and went at the same speed; yet, although they occasionally got glimpses of one another, they never once met. The puzzle is to show the route that each happened to take.

Topics:Combinatorics -> Graph Theory -

Question 325 - AN EPISCOPAL VISITATION

The white squares on the chessboard represent the parishes of a diocese. Place the bishop on any square you like, and so contrive that (using the ordinary bishop's move of chess) he shall visit every one of his parishes in the fewest possible moves. Of course, all the parishes passed through on any move are regarded as "visited." You can visit any squares more than once, but you are not allowed to move twice between the same two adjoining squares. What are the fewest possible moves? The bishop need not end his visitation at the parish from which he first set out. -

Question 326 - A NEW COUNTER PUZZLE

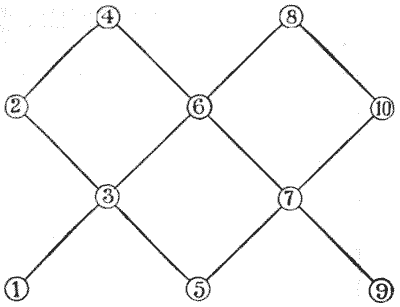

Here is a new puzzle with moving counters, or coins, that at first glance looks as if it must be absurdly simple. But it will be found quite a little perplexity. I give it in this place for a reason that I will explain when we come to the next puzzle. Copy the simple diagram, enlarged, on a sheet of paper; then place two white counters on the points `1` and `2`, and two red counters on `9` and `10`, The puzzle is to make the red and white change places. You may move the counters one at a time in any order you like, along the lines from point to point, with the only restriction that a red and a white counter may never stand at once on the same straight line. Thus the first move can only be from `1` or `2` to `3`, or from `9` or `10` to `7`.

-

Question 327 - A NEW BISHOP'S PUZZLE

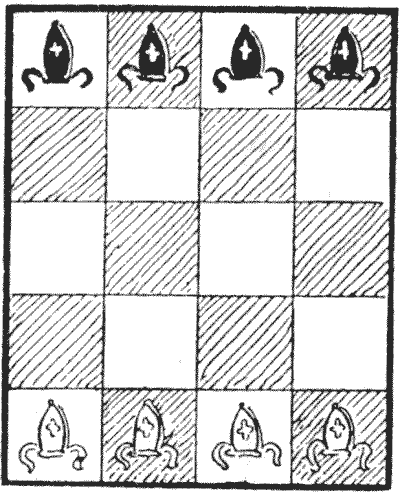

This is quite a fascinating little puzzle. Place eight bishops (four black and four white) on the reduced chessboard, as shown in the illustration. The problem is to make the black bishops change places with the white ones, no bishop ever attacking another of the opposite colour. They must move alternately—first a white, then a black, then a white, and so on. When you have succeeded in doing it at all, try to find the fewest possible moves.

If you leave out the bishops standing on black squares, and only play on the white squares, you will discover my last puzzle turned on its side.

-

Question 328 - THE QUEEN'S TOUR

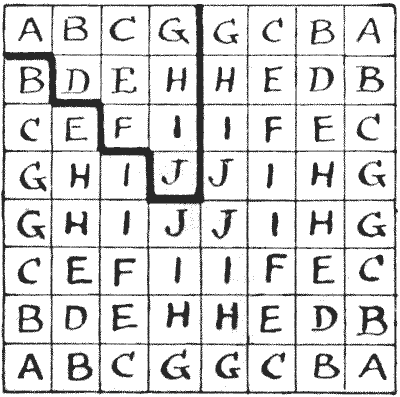

The puzzle of making a complete tour of the chessboard with the queen in the fewest possible moves (in which squares may be visited more than once) was first given by the late Sam Loyd in his Chess Strategy. But the solution shown below is the one he gave in American Chess-Nuts in `1868`. I have recorded at least six different solutions in the minimum number of moves—fourteen—but this one is the best of all, for reasons I will explain. If you will look at the lettered square you will understand that there are only ten really differently placed squares on a chessboard—those enclosed by a dark line—all the others are mere reversals or reflections. For example, every A is a corner square, and every J a central square. Consequently, as the solution shown has a turning-point at the enclosed D square, we can obtain a solution starting from and ending at any square marked D—by just turning the board about. Now, this scheme will give you a tour starting from any A, B, C, D, E, F, or H, while no other route that I know can be adapted to more than five different starting-points. There is no Queen's Tour in fourteen moves (remember a tour must be re-entrant) that may start from a G, I, or J. But we can have a non-re-entrant path over the whole board in fourteen moves, starting from any given square. Hence the following puzzle:—

If you will look at the lettered square you will understand that there are only ten really differently placed squares on a chessboard—those enclosed by a dark line—all the others are mere reversals or reflections. For example, every A is a corner square, and every J a central square. Consequently, as the solution shown has a turning-point at the enclosed D square, we can obtain a solution starting from and ending at any square marked D—by just turning the board about. Now, this scheme will give you a tour starting from any A, B, C, D, E, F, or H, while no other route that I know can be adapted to more than five different starting-points. There is no Queen's Tour in fourteen moves (remember a tour must be re-entrant) that may start from a G, I, or J. But we can have a non-re-entrant path over the whole board in fourteen moves, starting from any given square. Hence the following puzzle:—  Start from the J in the enclosed part of the lettered diagram and visit every square of the board in fourteen moves, ending wherever you like.

Start from the J in the enclosed part of the lettered diagram and visit every square of the board in fourteen moves, ending wherever you like.

-

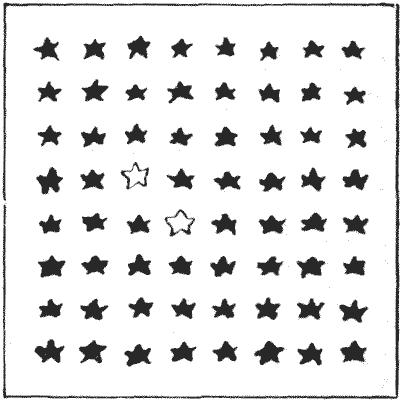

Question 329 - THE STAR PUZZLE

Put the point of your pencil on one of the white stars and (without ever lifting your pencil from the paper) strike out all the stars in fourteen continuous straight strokes, ending at the second white star. Your straight strokes may be in any direction you like, only every turning must be made on a star. There is no objection to striking out any star more than once.

In this case, where both your starting and ending squares are fixed inconveniently, you cannot obtain a solution by breaking a Queen's Tour, or in any other way by queen moves alone. But you are allowed to use oblique straight lines—such as from the upper white star direct to a corner star.

-

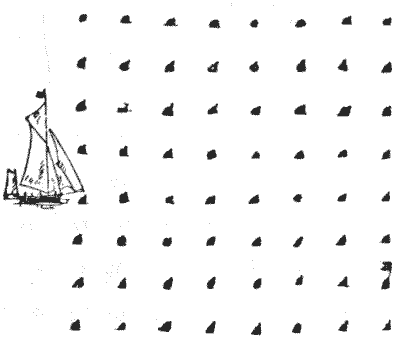

Question 330 - THE YACHT RACE

Now then, ye land-lubbers, hoist your baby-jib-topsails, break out your spinnakers, ease off your balloon sheets, and get your head-sails set!

Our race consists in starting from the point at which the yacht is lying in the illustration and touching every one of the sixty-four buoys in fourteen straight courses, returning in the final tack to the buoy from which we start. The seventh course must finish at the buoy from which a flag is flying.

This puzzle will call for a lot of skilful seamanship on account of the sharp angles at which it will occasionally be necessary to tack. The point of a lead pencil and a good nautical eye are all the outfit that we require.

This is difficult, because of the condition as to the flag-buoy, and because it is a re-entrant tour. But again we are allowed those oblique lines.