Amusements in Mathematics, Henry Ernest Dudeney

-

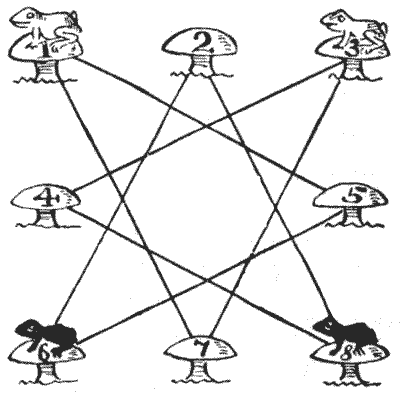

Question 341 - THE FOUR FROGS

In the illustration we have eight toadstools, with white frogs on `1` and `3` and black frogs on `6` and `8`. The puzzle is to move one frog at a time, in any order, along one of the straight lines from toadstool to toadstool, until they have exchanged places, the white frogs being left on `6` and `8` and the black ones on `1` and `3`. If you use four counters on a simple diagram, you will find this quite easy, but it is a little more puzzling to do it in only seven plays, any number of successive moves by one frog counting as one play. Of course, more than one frog cannot be on a toadstool at the same time.

In the illustration we have eight toadstools, with white frogs on `1` and `3` and black frogs on `6` and `8`. The puzzle is to move one frog at a time, in any order, along one of the straight lines from toadstool to toadstool, until they have exchanged places, the white frogs being left on `6` and `8` and the black ones on `1` and `3`. If you use four counters on a simple diagram, you will find this quite easy, but it is a little more puzzling to do it in only seven plays, any number of successive moves by one frog counting as one play. Of course, more than one frog cannot be on a toadstool at the same time.

-

Question 342 - THE MANDARIN'S PUZZLE

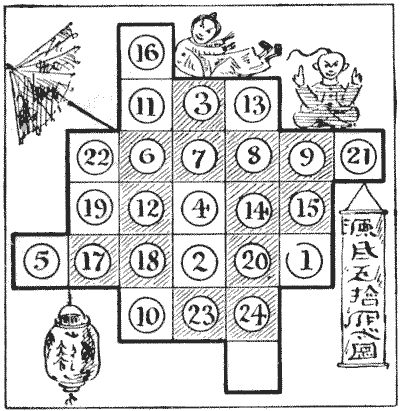

The following puzzle has an added interest from the circumstance that a correct solution of it secured for a certain young Chinaman the hand of his charming bride. The wealthiest mandarin within a radius of a hundred miles of Peking was Hi-Chum-Chop, and his beautiful daughter, Peeky-Bo, had innumerable admirers. One of her most ardent lovers was Winky-Hi, and when he asked the old mandarin for his consent to their marriage, Hi-Chum-Chop presented him with the following puzzle and promised his consent if the youth brought him the correct answer within a week. Winky-Hi, following a habit which obtains among certain solvers to this day, gave it to all his friends, and when he had compared their solutions he handed in the best one as his own. Luckily it was quite right. The mandarin thereupon fulfilled his promise. The fatted pup was killed for the wedding feast, and when Hi-Chum-Chop passed Winky-Hi the liver wing all present knew that it was a token of eternal goodwill, in accordance with Chinese custom from time immemorial.

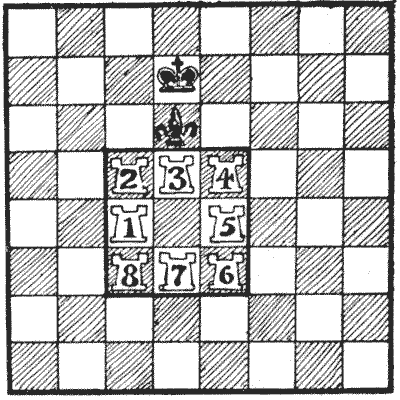

The mandarin had a table divided into twenty-five squares, as shown in the diagram. On each of twenty-four of these squares was placed a numbered counter, just as I have indicated. The puzzle is to get the counters in numerical order by moving them one at a time in what we call "knight's moves." Counter `1` should be where `16` is, `2` where `11` is, `4` where `13` now is, and so on. It will be seen that all the counters on shaded squares are in their proper positions. Of course, two counters may never be on a square at the same time. Can you perform the feat in the fewest possible moves?

In order to make the manner of moving perfectly clear I will point out that the first knight's move can only be made by `1` or by `2` or by `10`. Supposing `1` moves, then the next move must be by `23, 4, 8`, or `21`. As there is never more than one square vacant, the order in which the counters move may be written out as follows: `1`—`21`—`14`—`18`—`22`, etc. A rough diagram should be made on a larger scale for practice, and numbered counters or pieces of cardboard used.

Topics:Puzzles and Rebuses -

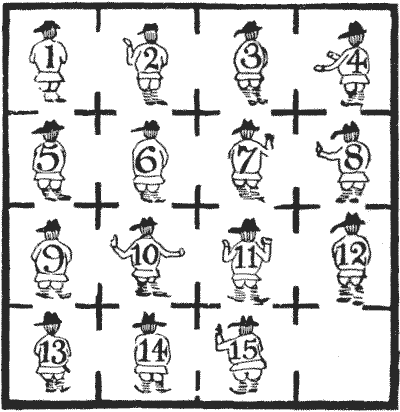

Question 343 - EXERCISE FOR PRISONERS

The following is the plan of the north wing of a certain gaol, showing the sixteen cells all communicating by open doorways. Fifteen prisoners were numbered and arranged in the cells as shown. They were allowed to change their cells as much as they liked, but if two prisoners were ever in the same cell together there was a severe punishment promised them.

Now, in order to reduce their growing obesity, and to combine physical exercise with mental recreation, the prisoners decided, on the suggestion of one of their number who was interested in knight's tours, to try to form themselves into a perfect knight's path without breaking the prison regulations, and leaving the bottom right-hand corner cell vacant, as originally. The joke of the matter is that the arrangement at which they arrived was as follows:—

8 3 12 1 11 14 9 6 4 7 2 13 15 10 5 The warders failed to detect the important fact that the men could not possibly get into this position without two of them having been at some time in the same cell together. Make the attempt with counters on a ruled diagram, and you will find that this is so. Otherwise the solution is correct enough, each member being, as required, a knight's move from the preceding number, and the original corner cell vacant.

The puzzle is to start with the men placed as in the illustration and show how it might have been done in the fewest moves, while giving a complete rest to as many prisoners as possible.

As there is never more than one vacant cell for a man to enter, it is only necessary to write down the numbers of the men in the order in which they move. It is clear that very few men can be left throughout in their cells undisturbed, but I will leave the solver to discover just how many, as this is a very essential part of the puzzle.

-

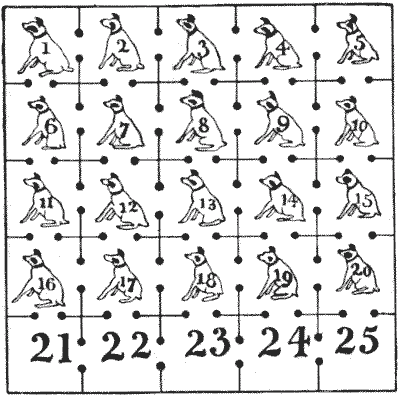

Question 344 - THE KENNEL PUZZLE

A man has twenty-five dog kennels all communicating with each other by doorways, as shown in the illustration. He wishes to arrange his twenty dogs so that they shall form a knight's string from dog No. `1` to dog No. `20`, the bottom row of five kennels to be left empty, as at present. This is to be done by moving one dog at a time into a vacant kennel. The dogs are well trained to obedience, and may be trusted to remain in the kennels in which they are placed, except that if two are placed in the same kennel together they will fight it out to the death. How is the puzzle to be solved in the fewest possible moves without two dogs ever being together?

Topics:Combinatorics -> Game Theory

A man has twenty-five dog kennels all communicating with each other by doorways, as shown in the illustration. He wishes to arrange his twenty dogs so that they shall form a knight's string from dog No. `1` to dog No. `20`, the bottom row of five kennels to be left empty, as at present. This is to be done by moving one dog at a time into a vacant kennel. The dogs are well trained to obedience, and may be trusted to remain in the kennels in which they are placed, except that if two are placed in the same kennel together they will fight it out to the death. How is the puzzle to be solved in the fewest possible moves without two dogs ever being together?

Topics:Combinatorics -> Game Theory -

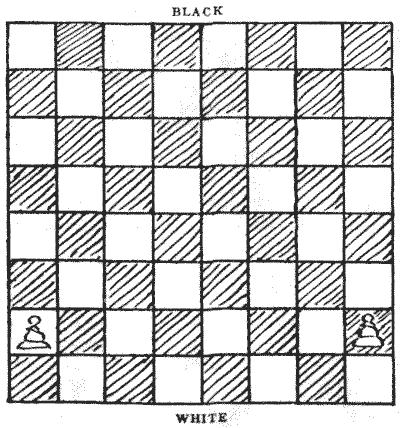

Question 345 - THE TWO PAWNS

Here is a neat little puzzle in counting. In how many different ways may the two pawns advance to the eighth square? You may move them in any order you like to form a different sequence. For example, you may move the Q R P (one or two squares) first, or the K R P first, or one pawn as far as you like before touching the other. Any sequence is permissible, only in this puzzle as soon as a pawn reaches the eighth square it is dead, and remains there unconverted. Can you count the number of different sequences? At first it will strike you as being very difficult, but I will show that it is really quite simple when properly attacked.

Here is a neat little puzzle in counting. In how many different ways may the two pawns advance to the eighth square? You may move them in any order you like to form a different sequence. For example, you may move the Q R P (one or two squares) first, or the K R P first, or one pawn as far as you like before touching the other. Any sequence is permissible, only in this puzzle as soon as a pawn reaches the eighth square it is dead, and remains there unconverted. Can you count the number of different sequences? At first it will strike you as being very difficult, but I will show that it is really quite simple when properly attacked. -

Question 346 - SETTING THE BOARD

I have a single chessboard and a single set of chessmen. In how many different ways may the men be correctly set up for the beginning of a game? I find that most people slip at a particular point in making the calculation.Topics:Combinatorics -> Product Rule / Rule of Product -

Question 347 - COUNTING THE RECTANGLES

Can you say correctly just how many squares and other rectangles the chessboard contains? In other words, in how great a number of different ways is it possible to indicate a square or other rectangle enclosed by lines that separate the squares of the board? -

Question 348 - THE ROOKERY

The White rooks cannot move outside the little square in which they are enclosed except on the final move, in giving checkmate. The puzzle is how to checkmate Black in the fewest possible moves with No. `8` rook, the other rooks being left in numerical order round the sides of their square with the break between `1` and `7`.

The White rooks cannot move outside the little square in which they are enclosed except on the final move, in giving checkmate. The puzzle is how to checkmate Black in the fewest possible moves with No. `8` rook, the other rooks being left in numerical order round the sides of their square with the break between `1` and `7`.

-

Question 349 - STALEMATE

Some years ago the puzzle was proposed to construct an imaginary game of chess, in which White shall be stalemated in the fewest possible moves with all the thirty-two pieces on the board. Can you build up such a position in fewer than twenty moves? -

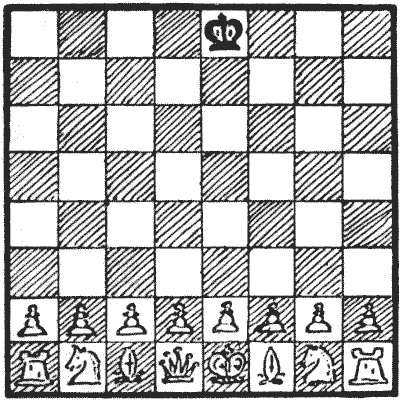

Question 350 - THE FORSAKEN KING

Set up the position shown in the diagram. Then the condition of the puzzle is—White to play and checkmate in six moves. Notwithstanding the complexities, I will show how the manner of play may be condensed into quite a few lines, merely stating here that the first two moves of White cannot be varied.

Topics:Combinatorics -> Game Theory

Set up the position shown in the diagram. Then the condition of the puzzle is—White to play and checkmate in six moves. Notwithstanding the complexities, I will show how the manner of play may be condensed into quite a few lines, merely stating here that the first two moves of White cannot be varied.

Topics:Combinatorics -> Game Theory