Geometry, Area Calculation

This topic focuses on methods for determining the size of a two-dimensional surface or region. Questions involve calculating the areas of various geometric shapes like triangles, quadrilaterals, circles, and more complex composite figures, often requiring application of specific formulas.

-

REAPING THE CORN

A farmer had a square cornfield. The corn was all ripe for reaping, and, as he was short of men, it was arranged that he and his son should share the work between them. The farmer first cut one rod wide all round the square, thus leaving a smaller square of standing corn in the middle of the field. "Now," he said to his son, "I have cut my half of the field, and you can do your share." The son was not quite satisfied as to the proposed division of labour, and as the village schoolmaster happened to be passing, he appealed to that person to decide the matter. He found the farmer was quite correct, provided there was no dispute as to the size of the field, and on this point they were agreed. Can you tell the area of the field, as that ingenious schoolmaster succeeded in doing? Sources:- Amusements in Mathematics, Henry Ernest Dudeney Question 111

-

A FENCE PROBLEM

The practical usefulness of puzzles is a point that we are liable to overlook. Yet, as a matter of fact, I have from time to time received quite a large number of letters from individuals who have found that the mastering of some little principle upon which a puzzle was built has proved of considerable value to them in a most unexpected way. Indeed, it may be accepted as a good maxim that a puzzle is of little real value unless, as well as being amusing and perplexing, it conceals some instructive and possibly useful feature. It is, however, very curious how these little bits of acquired knowledge dovetail into the occasional requirements of everyday life, and equally curious to what strange and mysterious uses some of our readers seem to apply them. What, for example, can be the object of Mr. Wm. Oxley, who writes to me all the way from Iowa, in wishing to ascertain the dimensions of a field that he proposes to enclose, containing just as many acres as there shall be rails in the fence? The man wishes to fence in a perfectly square field which is to contain just as many acres as there are rails in the required fence. Each hurdle, or portion of fence, is seven rails high, and two lengths would extend one pole (`16`½ ft.): that is to say, there are fourteen rails to the pole, lineal measure. Now, what must be the size of the field?

Sources:

The man wishes to fence in a perfectly square field which is to contain just as many acres as there are rails in the required fence. Each hurdle, or portion of fence, is seven rails high, and two lengths would extend one pole (`16`½ ft.): that is to say, there are fourteen rails to the pole, lineal measure. Now, what must be the size of the field?

Sources:

- Amusements in Mathematics, Henry Ernest Dudeney Question 117

-

A QUESTION OF DEFINITION

"My property is exactly a mile square," said one landowner to another.

"Curiously enough, mine is a square mile," was the reply.

"Then there is no difference?"

Is this last statement correct?

Sources:- Amusements in Mathematics, Henry Ernest Dudeney Question 124

-

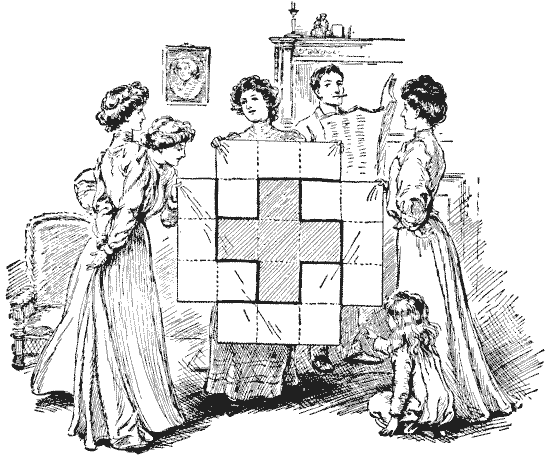

THE SILK PATCHWORK

The lady members of the Wilkinson family had made a simple patchwork quilt, as a small Christmas present, all composed of square pieces of the same size, as shown in the illustration. It only lacked the four corner pieces to make it complete. Somebody pointed out to them that if you unpicked the Greek cross in the middle and then cut the stitches along the dark joins, the four pieces all of the same size and shape would fit together and form a square. This the reader knows, from the solution in Fig. `39`, is quite easily done. But George Wilkinson suddenly suggested to them this poser. He said, "Instead of picking out the cross entire, and forming the square from four equal pieces, can you cut out a square entire and four equal pieces that will form a perfect Greek cross?" The puzzle is, of course, now quite easy. Sources:Topics:Geometry -> Plane Geometry Geometry -> Area Calculation Combinatorics -> Combinatorial Geometry -> Cut a Shape / Dissection Problems

Sources:Topics:Geometry -> Plane Geometry Geometry -> Area Calculation Combinatorics -> Combinatorial Geometry -> Cut a Shape / Dissection Problems- Amusements in Mathematics, Henry Ernest Dudeney Question 142

-

THE CROSS AND THE TRIANGLE

Cut a Greek cross into six pieces that will form an equilateral triangle. This is another hard problem, and I will state here that a solution is practically impossible without a previous knowledge of my method of transforming an equilateral triangle into a square (see No. `26`, "Canterbury Puzzles").Sources:Topics:Geometry -> Area Calculation Geometry -> Plane Geometry -> Triangles Combinatorics -> Combinatorial Geometry -> Cut a Shape / Dissection Problems- Amusements in Mathematics, Henry Ernest Dudeney Question 144

-

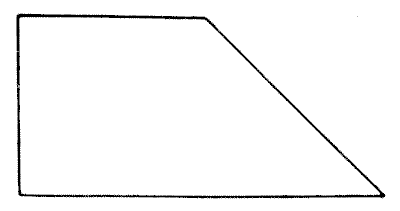

AN EASY DISSECTION PUZZLE

First, cut out a piece of paper or cardboard of the shape shown in the illustration. It will be seen at once that the proportions are simply those of a square attached to half of another similar square, divided diagonally. The puzzle is to cut it into four pieces all of precisely the same size and shape.

Sources:Topics:Geometry -> Plane Geometry Geometry -> Area Calculation Combinatorics -> Combinatorial Geometry -> Cut a Shape / Dissection Problems- Amusements in Mathematics, Henry Ernest Dudeney Question 146

-

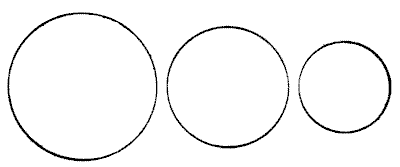

THE BUN PUZZLE

The three circles represent three buns, and it is simply required to show how these may be equally divided among four boys. The buns must be regarded as of equal thickness throughout and of equal thickness to each other. Of course, they must be cut into as few pieces as possible. To simplify it I will state the rather surprising fact that only five pieces are necessary, from which it will be seen that one boy gets his share in two pieces and the other three receive theirs in a single piece. I am aware that this statement "gives away" the puzzle, but it should not destroy its interest to those who like to discover the "reason why."

Sources:Topics:Geometry -> Area Calculation Geometry -> Plane Geometry -> Circles Geometry -> Plane Geometry -> Pythagorean Theorem Combinatorics -> Combinatorial Geometry -> Cut a Shape / Dissection Problems

The three circles represent three buns, and it is simply required to show how these may be equally divided among four boys. The buns must be regarded as of equal thickness throughout and of equal thickness to each other. Of course, they must be cut into as few pieces as possible. To simplify it I will state the rather surprising fact that only five pieces are necessary, from which it will be seen that one boy gets his share in two pieces and the other three receive theirs in a single piece. I am aware that this statement "gives away" the puzzle, but it should not destroy its interest to those who like to discover the "reason why."

Sources:Topics:Geometry -> Area Calculation Geometry -> Plane Geometry -> Circles Geometry -> Plane Geometry -> Pythagorean Theorem Combinatorics -> Combinatorial Geometry -> Cut a Shape / Dissection Problems- Amusements in Mathematics, Henry Ernest Dudeney Question 148

-

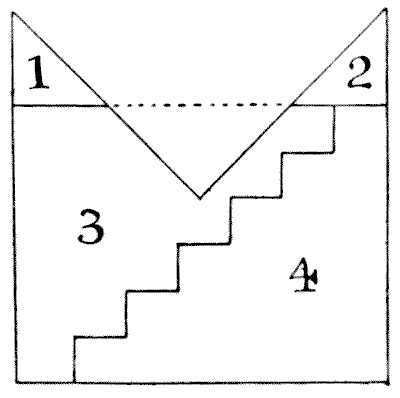

DISSECTING A MITRE

The figure that is perplexing the carpenter in the illustration represents a mitre. It will be seen that its proportions are those of a square with one quarter removed. The puzzle is to cut it into five pieces that will fit together and form a perfect square. I show an attempt, published in America, to perform the feat in four pieces, based on what is known as the "step principle," but it is a fallacy.

We are told first to cut oft the pieces `1` and `2` and pack them into the triangular space marked off by the dotted line, and so form a rectangle.

So far, so good. Now, we are directed to apply the old step principle, as shown, and, by moving down the piece `4` one step, form the required square. But, unfortunately, it does not produce a square: only an oblong. Call the three long sides of the mitre `84` in. each. Then, before cutting the steps, our rectangle in three pieces will be `84`×`63`. The steps must be `10`½ in. in height and `12` in. in breadth. Therefore, by moving down a step we reduce by `12` in. the side `84` in. and increase by `10`½ in. the side `63` in. Hence our final rectangle must be `72` in. × `73`½ in., which certainly is not a square! The fact is, the step principle can only be applied to rectangles with sides of particular relative lengths. For example, if the shorter side in this case were `61` `5/7` (instead of `63`), then the step method would apply. For the steps would then be `10` `2/7` in. in height and `12` in. in breadth. Note that `61` `5/7` × `84`= the square of `72`. At present no solution has been found in four pieces, and I do not believe one possible.

Sources:Topics:Geometry -> Plane Geometry Geometry -> Area Calculation Combinatorics -> Combinatorial Geometry -> Cut a Shape / Dissection Problems- Amusements in Mathematics, Henry Ernest Dudeney Question 150

-

THE JOINER'S PROBLEM

I have often had occasion to remark on the practical utility of puzzles, arising out of an application to the ordinary affairs of life of the little tricks and "wrinkles" that we learn while solving recreation problems. The joiner, in the illustration, wants to cut the piece of wood into as few pieces as possible to form a square table-top, without any waste of material. How should he go to work? How many pieces would you require?

Sources:Topics:Geometry -> Plane Geometry Geometry -> Area Calculation Combinatorics -> Combinatorial Geometry -> Cut a Shape / Dissection Problems

The joiner, in the illustration, wants to cut the piece of wood into as few pieces as possible to form a square table-top, without any waste of material. How should he go to work? How many pieces would you require?

Sources:Topics:Geometry -> Plane Geometry Geometry -> Area Calculation Combinatorics -> Combinatorial Geometry -> Cut a Shape / Dissection Problems- Amusements in Mathematics, Henry Ernest Dudeney Question 151

-

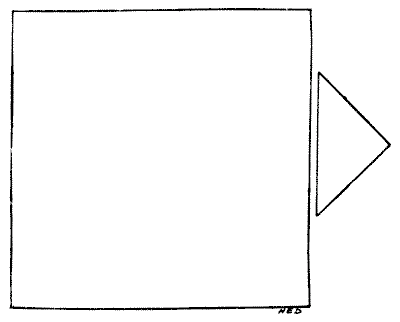

ANOTHER JOINER'S PROBLEM

A joiner had two pieces of wood of the shapes and relative proportions shown in the diagram. He wished to cut them into as few pieces as possible so that they could be fitted together, without waste, to form a perfectly square table-top. How should he have done it? There is no necessity to give measurements, for if the smaller piece (which is half a square) be made a little too large or a little too small it will not affect the method of solution.

Sources:Topics:Geometry -> Area Calculation Geometry -> Plane Geometry -> Pythagorean Theorem Combinatorics -> Combinatorial Geometry -> Cut a Shape / Dissection Problems

A joiner had two pieces of wood of the shapes and relative proportions shown in the diagram. He wished to cut them into as few pieces as possible so that they could be fitted together, without waste, to form a perfectly square table-top. How should he have done it? There is no necessity to give measurements, for if the smaller piece (which is half a square) be made a little too large or a little too small it will not affect the method of solution.

Sources:Topics:Geometry -> Area Calculation Geometry -> Plane Geometry -> Pythagorean Theorem Combinatorics -> Combinatorial Geometry -> Cut a Shape / Dissection Problems- Amusements in Mathematics, Henry Ernest Dudeney Question 152