Logic

Logic is the study of reasoning and valid inference. It involves analyzing statements, arguments, and deductive processes. Questions may include solving logic puzzles, evaluating the truth of compound statements, using truth tables, and identifying logical fallacies.

Reasoning / Logic Truth-tellers and Liars Problems-

THE WAPSHAW'S WHARF MYSTERY

There was a great commotion in Lower Thames Street on the morning of January `12, 1887`. When the early members of the staff arrived at Wapshaw's Wharf they found that the safe had been broken open, a considerable sum of money removed, and the offices left in great disorder. The night watchman was nowhere to be found, but nobody who had been acquainted with him for one moment suspected him to be guilty of the robbery. In this belief the proprietors were confirmed when, later in the day, they were informed that the poor fellow's body had been picked up by the River Police. Certain marks of violence pointed to the fact that he had been brutally attacked and thrown into the river. A watch found in his pocket had stopped, as is invariably the case in such circumstances, and this was a valuable clue to the time of the outrage. But a very stupid officer (and we invariably find one or two stupid individuals in the most intelligent bodies of men) had actually amused himself by turning the hands round and round, trying to set the watch going again. After he had been severely reprimanded for this serious indiscretion, he was asked whether he could remember the time that was indicated by the watch when found. He replied that he could not, but he recollected that the hour hand and minute hand were exactly together, one above the other, and the second hand had just passed the forty-ninth second. More than this he could not remember.

What was the exact time at which the watchman's watch stopped? The watch is, of course, assumed to have been an accurate one.

Sources:- Amusements in Mathematics, Henry Ernest Dudeney Question 60

-

THE VILLAGE SIMPLETON

A facetious individual who was taking a long walk in the country came upon a yokel sitting on a stile. As the gentleman was not quite sure of his road, he thought he would make inquiries of the local inhabitant; but at the first glance he jumped too hastily to the conclusion that he had dropped on the village idiot. He therefore decided to test the fellow's intelligence by first putting to him the simplest question he could think of, which was, "What day of the week is this, my good man?" The following is the smart answer that he received:—

"When the day after to-morrow is yesterday, to-day will be as far from Sunday as to-day was from Sunday when the day before yesterday was to-morrow."

Can the reader say what day of the week it was? It is pretty evident that the countryman was not such a fool as he looked. The gentleman went on his road a puzzled but a wiser man.

Sources:- Amusements in Mathematics, Henry Ernest Dudeney Question 66

-

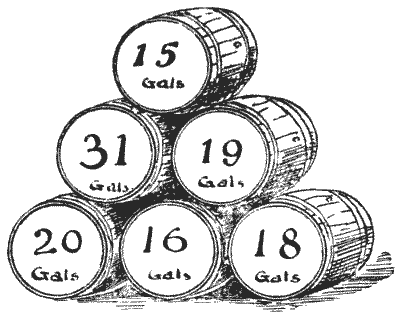

THE BARREL OF BEER

A man bought an odd lot of wine in barrels and one barrel containing beer. These are shown in the illustration, marked with the number of gallons that each barrel contained. He sold a quantity of the wine to one man and twice the quantity to another, but kept the beer to himself. The puzzle is to point out which barrel contains beer. Can you say which one it is? Of course, the man sold the barrels just as he bought them, without manipulating in any way the contents. Sources:Topics:Arithmetic Number Theory -> Modular Arithmetic / Remainder Arithmetic -> Divisibility Rules -> Divisibility Rules by 3 and 9 Algebra -> Word Problems Logic -> Reasoning / Logic

Sources:Topics:Arithmetic Number Theory -> Modular Arithmetic / Remainder Arithmetic -> Divisibility Rules -> Divisibility Rules by 3 and 9 Algebra -> Word Problems Logic -> Reasoning / Logic- Amusements in Mathematics, Henry Ernest Dudeney Question 76

-

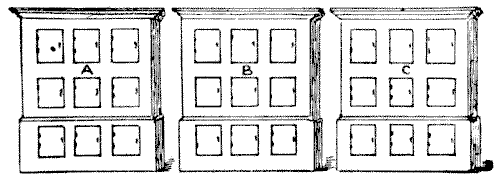

THE LOCKERS PUZZLE

A man had in his office three cupboards, each containing nine lockers, as shown in the diagram. He told his clerk to place a different one-figure number on each locker of cupboard A, and to do the same in the case of B, and of C. As we are here allowed to call nought a digit, and he was not prohibited from using nought as a number, he clearly had the option of omitting any one of ten digits from each cupboard.

Now, the employer did not say the lockers were to be numbered in any numerical order, and he was surprised to find, when the work was done, that the figures had apparently been mixed up indiscriminately. Calling upon his clerk for an explanation, the eccentric lad stated that the notion had occurred to him so to arrange the figures that in each case they formed a simple addition sum, the two upper rows of figures producing the sum in the lowest row. But the most surprising point was this: that he had so arranged them that the addition in A gave the smallest possible sum, that the addition in C gave the largest possible sum, and that all the nine digits in the three totals were different. The puzzle is to show how this could be done. No decimals are allowed and the nought may not appear in the hundreds place.

Sources:Topics:Number Theory Arithmetic Logic -> Reasoning / Logic Combinatorics -> Case Analysis / Checking Cases -> Processes / Procedures- Amusements in Mathematics, Henry Ernest Dudeney Question 79

-

THE CENTURY PUZZLE

Can you write `100` in the form of a mixed number, using all the nine digits once, and only once? The late distinguished French mathematician, Edouard Lucas, found seven different ways of doing it, and expressed his doubts as to there being any other ways. As a matter of fact there are just eleven ways and no more. Here is one of them, `91 5742/638`. Nine of the other ways have similarly two figures in the integral part of the number, but the eleventh expression has only one figure there. Can the reader find this last form?

Sources:Topics:Number Theory -> Modular Arithmetic / Remainder Arithmetic -> Divisibility Rules Logic -> Reasoning / Logic Arithmetic -> Fractions Combinatorics -> Case Analysis / Checking Cases -> Processes / Procedures- Amusements in Mathematics, Henry Ernest Dudeney Question 90

-

PAINTING THE LAMP-POSTS

Tim Murphy and Pat Donovan were engaged by the local authorities to paint the lamp-posts in a certain street. Tim, who was an early riser, arrived first on the job, and had painted three on the south side when Pat turned up and pointed out that Tim's contract was for the north side. So Tim started afresh on the north side and Pat continued on the south. When Pat had finished his side he went across the street and painted six posts for Tim, and then the job was finished. As there was an equal number of lamp-posts on each side of the street, the simple question is: Which man painted the more lamp-posts, and just how many more? Sources:- Amusements in Mathematics, Henry Ernest Dudeney Question 103

-

SATURDAY MARKETING

Here is an amusing little case of marketing which, although it deals with a good many items of money, leads up to a question of a totally different character. Four married couples went into their village on a recent Saturday night to do a little marketing. They had to be very economical, for among them they only possessed forty shilling coins. The fact is, Ann spent `1`s., Mary spent `2`s., Jane spent `3`s., and Kate spent `4`s. The men were rather more extravagant than their wives, for Ned Smith spent as much as his wife, Tom Brown twice as much as his wife, Bill Jones three times as much as his wife, and Jack Robinson four times as much as his wife. On the way home somebody suggested that they should divide what coin they had left equally among them. This was done, and the puzzling question is simply this: What was the surname of each woman? Can you pair off the four couples?

Sources:- Amusements in Mathematics, Henry Ernest Dudeney Question 141

-

THE SHEEP-FOLD

It is a curious fact that the answers always given to some of the best-known puzzles that appear in every little book of fireside recreations that has been published for the last fifty or a hundred years are either quite unsatisfactory or clearly wrong. Yet nobody ever seems to detect their faults. Here is an example:—A farmer had a pen made of fifty hurdles, capable of holding a hundred sheep only. Supposing he wanted to make it sufficiently large to hold double that number, how many additional hurdles must he have? Sources:- Amusements in Mathematics, Henry Ernest Dudeney Question 193

-

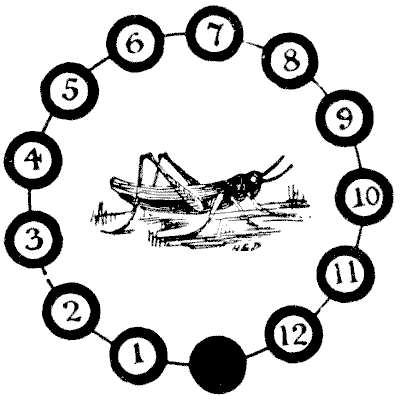

THE GRASSHOPPER PUZZLE

It has been suggested that this puzzle was a great favourite among the young apprentices of the City of London in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries. Readers will have noticed the curious brass grasshopper on the Royal Exchange. This long-lived creature escaped the fires of `1666` and `1838`. The grasshopper, after his kind, was the crest of Sir Thomas Gresham, merchant grocer, who died in `1579`, and from this cause it has been used as a sign by grocers in general. Unfortunately for the legend as to its origin, the puzzle was only produced by myself so late as the year `1900`. On twelve of the thirteen black discs are placed numbered counters or grasshoppers. The puzzle is to reverse their order, so that they shall read, `1, 2, 3, 4`, etc., in the opposite direction, with the vacant disc left in the same position as at present. Move one at a time in any order, either to the adjoining vacant disc or by jumping over one grasshopper, like the moves in draughts. The moves or leaps may be made in either direction that is at any time possible. What are the fewest possible moves in which it can be done? Sources:Topics:Logic -> Reasoning / Logic Combinatorics -> Case Analysis / Checking Cases -> Processes / Procedures

Sources:Topics:Logic -> Reasoning / Logic Combinatorics -> Case Analysis / Checking Cases -> Processes / Procedures- Amusements in Mathematics, Henry Ernest Dudeney Question 215

-

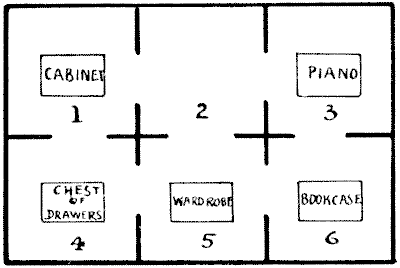

A LODGING-HOUSE DIFFICULTY

The Dobsons secured apartments at Slocomb-on-Sea. There were six rooms on the same floor, all communicating, as shown in the diagram. The rooms they took were numbers `4, 5`, and `6`, all facing the sea. But a little difficulty arose. Mr. Dobson insisted that the piano and the bookcase should change rooms. This was wily, for the Dobsons were not musical, but they wanted to prevent any one else playing the instrument. Now, the rooms were very small and the pieces of furniture indicated were very big, so that no two of these articles could be got into any room at the same time. How was the exchange to be made with the least possible labour? Suppose, for example, you first move the wardrobe into No. `2`; then you can move the bookcase to No. `5` and the piano to No. `6`, and so on. It is a fascinating puzzle, but the landlady had reasons for not appreciating it. Try to solve her difficulty in the fewest possible removals with counters on a sheet of paper.

Sources:

The Dobsons secured apartments at Slocomb-on-Sea. There were six rooms on the same floor, all communicating, as shown in the diagram. The rooms they took were numbers `4, 5`, and `6`, all facing the sea. But a little difficulty arose. Mr. Dobson insisted that the piano and the bookcase should change rooms. This was wily, for the Dobsons were not musical, but they wanted to prevent any one else playing the instrument. Now, the rooms were very small and the pieces of furniture indicated were very big, so that no two of these articles could be got into any room at the same time. How was the exchange to be made with the least possible labour? Suppose, for example, you first move the wardrobe into No. `2`; then you can move the bookcase to No. `5` and the piano to No. `6`, and so on. It is a fascinating puzzle, but the landlady had reasons for not appreciating it. Try to solve her difficulty in the fewest possible removals with counters on a sheet of paper.

Sources:

- Amusements in Mathematics, Henry Ernest Dudeney Question 220