Logic

Logic is the study of reasoning and valid inference. It involves analyzing statements, arguments, and deductive processes. Questions may include solving logic puzzles, evaluating the truth of compound statements, using truth tables, and identifying logical fallacies.

Reasoning / Logic Truth-tellers and Liars Problems-

"STRAND" PATIENCE

The idea for this came to me when considering the game of Patience that I gave in the Strand Magazine for December, `1910`, which has been reprinted in Ernest Bergholt's Second Book of Patience Games, under the new name of "King Albert."

Make two piles of cards as follows: `9` D, `8` S, `7` D, `6` S, `5` D, `4` S, `3` D, `2` S, `1` D, and `9` H, `8` C, `7` H, `6` C, `5` H, `4` C, `3` H, `2` C, `1` H, with the `9` of diamonds at the bottom of one pile and the `9` of hearts at the bottom of the other. The point is to exchange the spades with the clubs, so that the diamonds and clubs are still in numerical order in one pile and the hearts and spades in the other. There are four vacant spaces in addition to the two spaces occupied by the piles, and any card may be laid on a space, but a card can only be laid on another of the next higher value—an ace on a two, a two on a three, and so on. Patience is required to discover the shortest way of doing this. When there are four vacant spaces you can pile four cards in seven moves, with only three spaces you can pile them in nine moves, and with two spaces you cannot pile more than two cards. When you have a grasp of these and similar facts you will be able to remove a number of cards bodily and write down `7, 9`, or whatever the number of moves may be. The gradual shortening of play is fascinating, and first attempts are surprisingly lengthy.

Sources:Topics:Logic -> Reasoning / Logic Combinatorics -> Case Analysis / Checking Cases -> Processes / Procedures Combinatorics -> Case Analysis / Checking Cases -> Processes / Procedures Puzzles and Rebuses- Amusements in Mathematics, Henry Ernest Dudeney Question 385

-

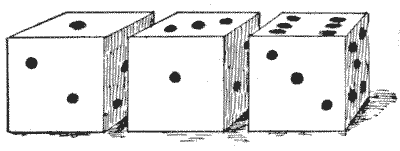

A TRICK WITH DICE

Here is a neat little trick with three dice. I ask you to throw the dice without my seeing them. Then I tell you to multiply the points of the first die by `2` and add `5`; then multiply the result by `5` and add the points of the second die; then multiply the result by `10` and add the points of the third die. You then give me the total, and I can at once tell you the points thrown with the three dice. How do I do it? As an example, if you threw `1, 3`, and `6`, as in the illustration, the result you would give me would be `386`, from which I could at once say what you had thrown.

Sources:

Here is a neat little trick with three dice. I ask you to throw the dice without my seeing them. Then I tell you to multiply the points of the first die by `2` and add `5`; then multiply the result by `5` and add the points of the second die; then multiply the result by `10` and add the points of the third die. You then give me the total, and I can at once tell you the points thrown with the three dice. How do I do it? As an example, if you threw `1, 3`, and `6`, as in the illustration, the result you would give me would be `386`, from which I could at once say what you had thrown.

Sources:

- Amusements in Mathematics, Henry Ernest Dudeney Question 386

-

THE VILLAGE CRICKET MATCH

In a cricket match, Dingley Dell v. All Muggleton, the latter had the first innings. Mr. Dumkins and Mr. Podder were at the wickets, when the wary Dumkins made a splendid late cut, and Mr. Podder called on him to run. Four runs were apparently completed, but the vigilant umpires at each end called, "three short," making six short runs in all. What number did Mr. Dumkins score? When Dingley Dell took their turn at the wickets their champions were Mr. Luffey and Mr. Struggles. The latter made a magnificent off-drive, and invited his colleague to "come along," with the result that the observant spectators applauded them for what was supposed to have been three sharp runs. But the umpires declared that there had been two short runs at each end—four in all. To what extent, if any, did this manœuvre increase Mr. Struggles's total? Sources:- Amusements in Mathematics, Henry Ernest Dudeney Question 387

-

THE FOOTBALL PLAYERS

"It is a glorious game!" an enthusiast was heard to exclaim. "At the close of last season, of the footballers of my acquaintance four had broken their left arm, five had broken their right arm, two had the right arm sound, and three had sound left arms." Can you discover from that statement what is the smallest number of players that the speaker could be acquainted with?

It does not at all follow that there were as many as fourteen men, because, for example, two of the men who had broken the left arm might also be the two who had sound right arms.

Sources:Topics:Logic -> Reasoning / Logic Combinatorics -> Case Analysis / Checking Cases -> Processes / Procedures Minimum and Maximum Problems / Optimization Problems- Amusements in Mathematics, Henry Ernest Dudeney Question 389

-

THE PEBBLE GAME

Here is an interesting little puzzle game that I used to play with an acquaintance on the beach at Slocomb-on-Sea. Two players place an odd number of pebbles, we will say fifteen, between them. Then each takes in turn one, two, or three pebbles (as he chooses), and the winner is the one who gets the odd number. Thus, if you get seven and your opponent eight, you win. If you get six and he gets nine, he wins. Ought the first or second player to win, and how? When you have settled the question with fifteen pebbles try again with, say, thirteen.Sources:Topics:Combinatorics -> Game Theory Logic -> Reasoning / Logic Combinatorics -> Case Analysis / Checking Cases -> Processes / Procedures- Amusements in Mathematics, Henry Ernest Dudeney Question 392

-

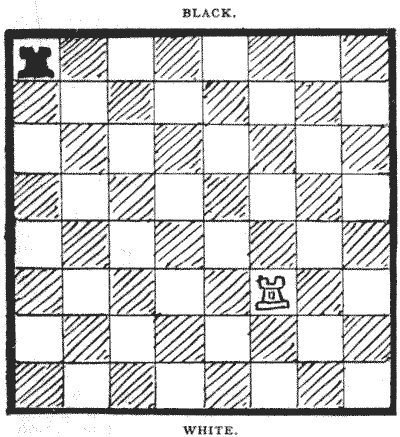

THE TWO ROOKS

This is a puzzle game for two players. Each player has a single rook. The first player places his rook on any square of the board that he may choose to select, and then the second player does the same. They now play in turn, the point of each play being to capture the opponent's rook. But in this game you cannot play through a line of attack without being captured. That is to say, if in the diagram it is Black's turn to play, he cannot move his rook to his king's knight's square, or to his king's rook's square, because he would enter the "line of fire" when passing his king's bishop's square. For the same reason he cannot move to his queen's rook's seventh or eighth squares. Now, the game can never end in a draw. Sooner or later one of the rooks must fall, unless, of course, both players commit the absurdity of not trying to win. The trick of winning is ridiculously simple when you know it. Can you solve the puzzle? Sources:Topics:Combinatorics -> Combinatorial Geometry Combinatorics -> Invariants Combinatorics -> Game Theory Logic -> Reasoning / Logic Combinatorics -> Colorings -> Chessboard Coloring

Sources:Topics:Combinatorics -> Combinatorial Geometry Combinatorics -> Invariants Combinatorics -> Game Theory Logic -> Reasoning / Logic Combinatorics -> Colorings -> Chessboard Coloring- Amusements in Mathematics, Henry Ernest Dudeney Question 393

-

THE CIGAR PUZZLE

I once propounded the following puzzle in a London club, and for a considerable period it absorbed the attention of the members. They could make nothing of it, and considered it quite impossible of solution. And yet, as I shall show, the answer is remarkably simple.

Two men are seated at a square-topped table. One places an ordinary cigar (flat at one end, pointed at the other) on the table, then the other does the same, and so on alternately, a condition being that no cigar shall touch another. Which player should succeed in placing the last cigar, assuming that they each will play in the best possible manner? The size of the table top and the size of the cigar are not given, but in order to exclude the ridiculous answer that the table might be so diminutive as only to take one cigar, we will say that the table must not be less than `2` feet square and the cigar not more than `4`½ inches long. With those restrictions you may take any dimensions you like. Of course we assume that all the cigars are exactly alike in every respect. Should the first player, or the second player, win?

Sources:Topics:Combinatorics -> Game Theory Logic -> Reasoning / Logic Geometry -> Plane Geometry -> Symmetry- Amusements in Mathematics, Henry Ernest Dudeney Question 398

-

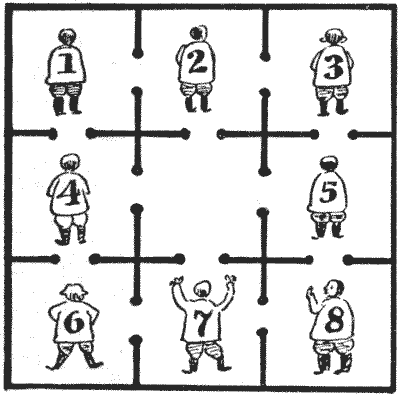

EIGHT JOLLY GAOL BIRDS

The illustration shows the plan of a prison of nine cells all communicating with one another by doorways. The eight prisoners have their numbers on their backs, and any one of them is allowed to exercise himself in whichever cell may happen to be vacant, subject to the rule that at no time shall two prisoners be in the same cell. The merry monarch in whose dominions the prison was situated offered them special comforts one Christmas Eve if, without breaking that rule, they could so place themselves that their numbers should form a magic square.

Now, prisoner No. `7` happened to know a good deal about magic squares, so he worked out a scheme and naturally selected the method that was most expeditious—that is, one involving the fewest possible moves from cell to cell. But one man was a surly, obstinate fellow (quite unfit for the society of his jovial companions), and he refused to move out of his cell or take any part in the proceedings. But No. `7` was quite equal to the emergency, and found that he could still do what was required in the fewest possible moves without troubling the brute to leave his cell. The puzzle is to show how he did it and, incidentally, to discover which prisoner was so stupidly obstinate. Can you find the fellow?

Sources:- Amusements in Mathematics, Henry Ernest Dudeney Question 401

-

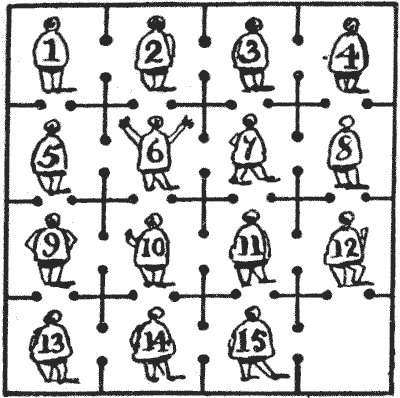

THE SPANISH DUNGEON

Not fifty miles from Cadiz stood in the middle ages a castle, all traces of which have for centuries disappeared. Among other interesting features, this castle contained a particularly unpleasant dungeon divided into sixteen cells, all communicating with one another, as shown in the illustration.

Now, the governor was a merry wight, and very fond of puzzles withal. One day he went to the dungeon and said to the prisoners, "By my halidame!" (or its equivalent in Spanish) "you shall all be set free if you can solve this puzzle. You must so arrange yourselves in the sixteen cells that the numbers on your backs shall form a magic square in which every column, every row, and each of the two diagonals shall add up the same. Only remember this: that in no case may two of you ever be together in the same cell."

One of the prisoners, after working at the problem for two or three days, with a piece of chalk, undertook to obtain the liberty of himself and his fellow-prisoners if they would follow his directions and move through the doorway from cell to cell in the order in which he should call out their numbers.

He succeeded in his attempt, and, what is more remarkable, it would seem from the account of his method recorded in the ancient manuscript lying before me, that he did so in the fewest possible moves. The reader is asked to show what these moves were.

Sources:Topics:Logic -> Reasoning / Logic Combinatorics -> Case Analysis / Checking Cases -> Processes / Procedures Combinatorics -> Number Tables Algebra -> Word Problems -> Solving Word Problems "From the End" / Working Backwards Puzzles and Rebuses -> Reconstruct the Exercise / Cryptarithmetic- Amusements in Mathematics, Henry Ernest Dudeney Question 403

-

WHO WAS FIRST?

Anderson, Biggs, and Carpenter were staying together at a place by the seaside. One day they went out in a boat and were a mile at sea when a rifle was fired on shore in their direction. Why or by whom the shot was fired fortunately does not concern us, as no information on these points is obtainable, but from the facts I picked up we can get material for a curious little puzzle for the novice.

It seems that Anderson only heard the report of the gun, Biggs only saw the smoke, and Carpenter merely saw the bullet strike the water near them. Now, the question arises: Which of them first knew of the discharge of the rifle?

Sources:Topics:Logic -> Reasoning / Logic- Amusements in Mathematics, Henry Ernest Dudeney Question 414