Logic

Logic is the study of reasoning and valid inference. It involves analyzing statements, arguments, and deductive processes. Questions may include solving logic puzzles, evaluating the truth of compound statements, using truth tables, and identifying logical fallacies.

Reasoning / Logic Truth-tellers and Liars Problems-

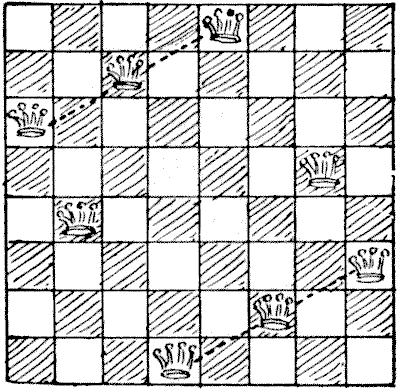

THE EIGHT QUEENS

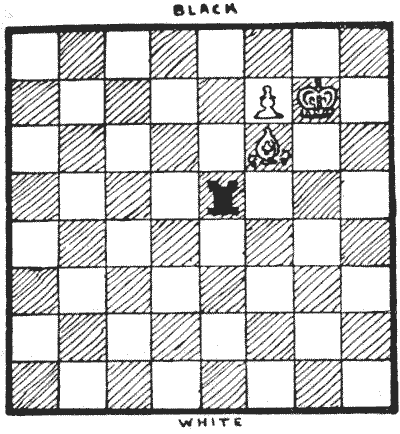

The queen is by far the strongest piece on the chessboard. If you place her on one of the four squares in the centre of the board, she attacks no fewer than twenty-seven other squares; and if you try to hide her in a corner, she still attacks twenty-one squares. Eight queens may be placed on the board so that no queen attacks another, and it is an old puzzle (first proposed by Nauck in `1850`, and it has quite a little literature of its own) to discover in just how many different ways this may be done. I show one way in the diagram, and there are in all twelve of these fundamentally different ways. These twelve produce ninety-two ways if we regard reversals and reflections as different. The diagram is in a way a symmetrical arrangement. If you turn the page upside down, it will reproduce itself exactly; but if you look at it with one of the other sides at the bottom, you get another way that is not identical. Then if you reflect these two ways in a mirror you get two more ways. Now, all the other eleven solutions are non-symmetrical, and therefore each of them may be presented in eight ways by these reversals and reflections. It will thus be seen why the twelve fundamentally different solutions produce only ninety-two arrangements, as I have said, and not ninety-six, as would happen if all twelve were non-symmetrical. It is well to have a clear understanding on the matter of reversals and reflections when dealing with puzzles on the chessboard. Can the reader place the eight queens on the board so that no queen shall attack another and so that no three queens shall be in a straight line in any oblique direction? Another glance at the diagram will show that this arrangement will not answer the conditions, for in the two directions indicated by the dotted lines there are three queens in a straight line. There is only one of the twelve fundamental ways that will solve the puzzle. Can you find it?

Sources:

Can the reader place the eight queens on the board so that no queen shall attack another and so that no three queens shall be in a straight line in any oblique direction? Another glance at the diagram will show that this arrangement will not answer the conditions, for in the two directions indicated by the dotted lines there are three queens in a straight line. There is only one of the twelve fundamental ways that will solve the puzzle. Can you find it?

Sources:

- Amusements in Mathematics, Henry Ernest Dudeney Question 300

-

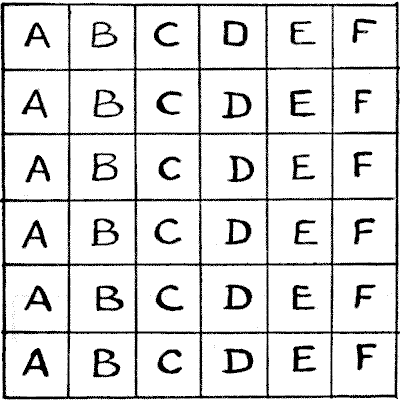

THE THIRTY-SIX LETTER BLOCKS

The illustration represents a box containing thirty-six letter-blocks. The puzzle is to rearrange these blocks so that no A shall be in a line vertically, horizontally, or diagonally with another A, no B with another B, no C with another C, and so on. You will find it impossible to get all the letters into the box under these conditions, but the point is to place as many as possible. Of course no letters other than those shown may be used.

Sources:Topics:Combinatorics -> Pigeonhole Principle Logic -> Reasoning / Logic Combinatorics -> Case Analysis / Checking Cases -> Processes / Procedures

The illustration represents a box containing thirty-six letter-blocks. The puzzle is to rearrange these blocks so that no A shall be in a line vertically, horizontally, or diagonally with another A, no B with another B, no C with another C, and so on. You will find it impossible to get all the letters into the box under these conditions, but the point is to place as many as possible. Of course no letters other than those shown may be used.

Sources:Topics:Combinatorics -> Pigeonhole Principle Logic -> Reasoning / Logic Combinatorics -> Case Analysis / Checking Cases -> Processes / Procedures- Amusements in Mathematics, Henry Ernest Dudeney Question 305

-

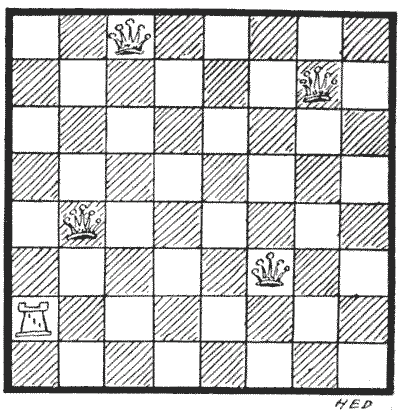

QUEENS AND BISHOP PUZZLE

It will be seen that every square of the board is either occupied or attacked. The puzzle is to substitute a bishop for the rook on the same square, and then place the four queens on other squares so that every square shall again be either occupied or attacked.

Sources:Topics:Logic -> Reasoning / Logic Combinatorics -> Case Analysis / Checking Cases -> Processes / Procedures Puzzles and Rebuses

Sources:Topics:Logic -> Reasoning / Logic Combinatorics -> Case Analysis / Checking Cases -> Processes / Procedures Puzzles and Rebuses- Amusements in Mathematics, Henry Ernest Dudeney Question 313

-

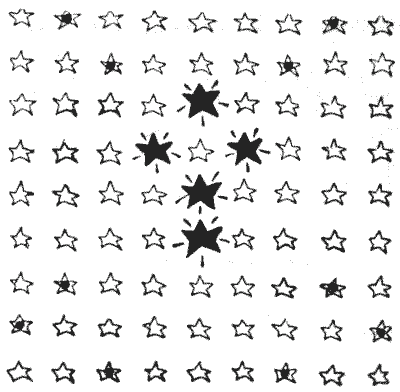

THE SOUTHERN CROSS

In the above illustration we have five Planets and eighty-one Fixed Stars, five of the latter being hidden by the Planets. It will be found that every Star, with the exception of the ten that have a black spot in their centres, is in a straight line, vertically, horizontally, or diagonally, with at least one of the Planets. The puzzle is so to rearrange the Planets that all the Stars shall be in line with one or more of them.

In rearranging the Planets, each of the five may be moved once in a straight line, in either of the three directions mentioned. They will, of course, obscure five other Stars in place of those at present covered.

Sources:Topics:Logic -> Reasoning / Logic Combinatorics -> Combinatorial Geometry -> Grid Paper Geometry / Lattice Geometry Puzzles and Rebuses- Amusements in Mathematics, Henry Ernest Dudeney Question 314

-

THE KNIGHT-GUARDS

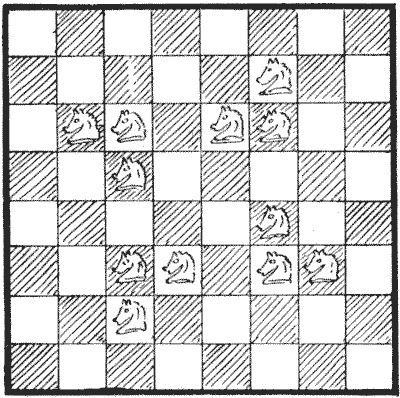

The knight is the irresponsible low comedian of the chessboard. "He is a very uncertain, sneaking, and demoralizing rascal," says an American writer. "He can only move two squares, but makes up in the quality of his locomotion for its quantity, for he can spring one square sideways and one forward simultaneously, like a cat; can stand on one leg in the middle of the board and jump to any one of eight squares he chooses; can get on one side of a fence and blackguard three or four men on the other; has an objectionable way of inserting himself in safe places where he can scare the king and compel him to move, and then gobble a queen. For pure cussedness the knight has no equal, and when you chase him out of one hole he skips into another." Attempts have been made over and over again to obtain a short, simple, and exact definition of the move of the knight—without success. It really consists in moving one square like a rook, and then another square like a bishop—the two operations being done in one leap, so that it does not matter whether the first square passed over is occupied by another piece or not. It is, in fact, the only leaping move in chess. But difficult as it is to define, a child can learn it by inspection in a few minutes.

I have shown in the diagram how twelve knights (the fewest possible that will perform the feat) may be placed on the chessboard so that every square is either occupied or attacked by a knight. Examine every square in turn, and you will find that this is so. Now, the puzzle in this case is to discover what is the smallest possible number of knights that is required in order that every square shall be either occupied or attacked, and every knight protected by another knight. And how would you arrange them? It will be found that of the twelve shown in the diagram only four are thus protected by being a knight's move from another knight.

Sources:Topics:Combinatorics -> Combinatorial Geometry Logic -> Reasoning / Logic Combinatorics -> Case Analysis / Checking Cases -> Processes / Procedures- Amusements in Mathematics, Henry Ernest Dudeney Question 319

-

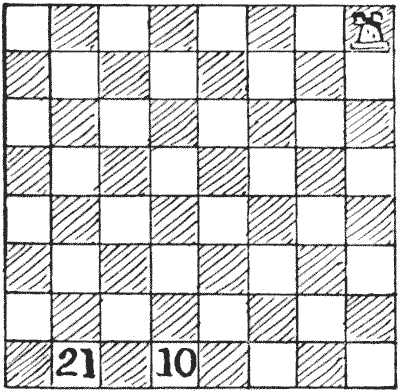

THE ROOK'S JOURNEY

This puzzle I call "The Rook's Journey," because the word "tour" (derived from a turner's wheel) implies that we return to the point from which we set out, and we do not do this in the present case. We should not be satisfied with a personally conducted holiday tour that ended by leaving us, say, in the middle of the Sahara. The rook here makes twenty-one moves, in the course of which journey it visits every square of the board once and only once, stopping at the square marked `10` at the end of its tenth move, and ending at the square marked `21`. Two consecutive moves cannot be made in the same direction—that is to say, you must make a turn after every move. Sources:Topics:Logic -> Reasoning / Logic Combinatorics -> Case Analysis / Checking Cases -> Processes / Procedures Combinatorics -> Combinatorial Geometry -> Grid Paper Geometry / Lattice Geometry Puzzles and Rebuses

Sources:Topics:Logic -> Reasoning / Logic Combinatorics -> Case Analysis / Checking Cases -> Processes / Procedures Combinatorics -> Combinatorial Geometry -> Grid Paper Geometry / Lattice Geometry Puzzles and Rebuses- Amusements in Mathematics, Henry Ernest Dudeney Question 321

-

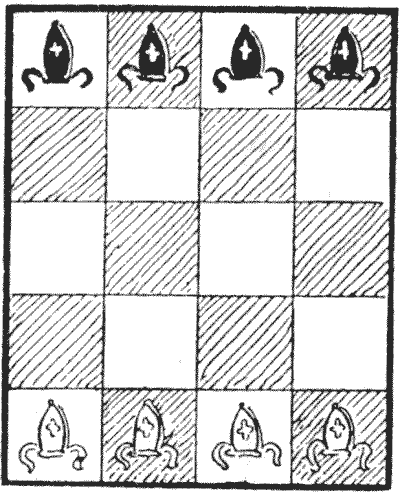

A NEW BISHOP'S PUZZLE

This is quite a fascinating little puzzle. Place eight bishops (four black and four white) on the reduced chessboard, as shown in the illustration. The problem is to make the black bishops change places with the white ones, no bishop ever attacking another of the opposite colour. They must move alternately—first a white, then a black, then a white, and so on. When you have succeeded in doing it at all, try to find the fewest possible moves.

If you leave out the bishops standing on black squares, and only play on the white squares, you will discover my last puzzle turned on its side.

Sources:Topics:Combinatorics -> Combinatorial Geometry Combinatorics -> Graph Theory Combinatorics -> Game Theory Logic -> Reasoning / Logic Puzzles and Rebuses- Amusements in Mathematics, Henry Ernest Dudeney Question 327

-

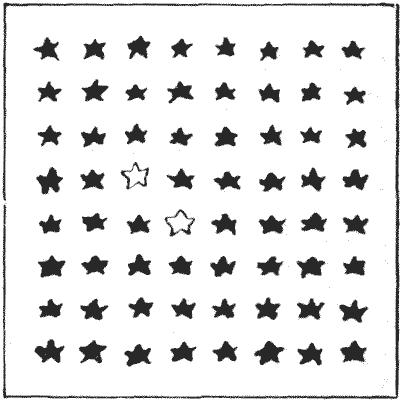

THE STAR PUZZLE

Put the point of your pencil on one of the white stars and (without ever lifting your pencil from the paper) strike out all the stars in fourteen continuous straight strokes, ending at the second white star. Your straight strokes may be in any direction you like, only every turning must be made on a star. There is no objection to striking out any star more than once.

In this case, where both your starting and ending squares are fixed inconveniently, you cannot obtain a solution by breaking a Queen's Tour, or in any other way by queen moves alone. But you are allowed to use oblique straight lines—such as from the upper white star direct to a corner star.

Sources:Topics:Combinatorics -> Combinatorial Geometry Combinatorics -> Graph Theory Logic -> Reasoning / Logic Puzzles and Rebuses- Amusements in Mathematics, Henry Ernest Dudeney Question 329

-

STALEMATE

Some years ago the puzzle was proposed to construct an imaginary game of chess, in which White shall be stalemated in the fewest possible moves with all the thirty-two pieces on the board. Can you build up such a position in fewer than twenty moves? Sources:- Amusements in Mathematics, Henry Ernest Dudeney Question 349

-

AN AMAZING DILEMMA

In a game of chess between Mr. Black and Mr. White, Black was in difficulties, and as usual was obliged to catch a train. So he proposed that White should complete the game in his absence on condition that no moves whatever should be made for Black, but only with the White pieces. Mr. White accepted, but to his dismay found it utterly impossible to win the game under such conditions. Try as he would, he could not checkmate his opponent. On which square did Mr. Black leave his king? The other pieces are in their proper positions in the diagram. White may leave Black in check as often as he likes, for it makes no difference, as he can never arrive at a checkmate position. Sources:

Sources:

- Amusements in Mathematics, Henry Ernest Dudeney Question 354