Algebra, Word Problems

Word problems present mathematical challenges in a narrative or real-world context. Solving them requires translating the text into mathematical equations or expressions and then applying appropriate mathematical techniques. These can span arithmetic, algebra, geometry, etc.

Motion Problems Solving Word Problems "From the End" / Working Backwards-

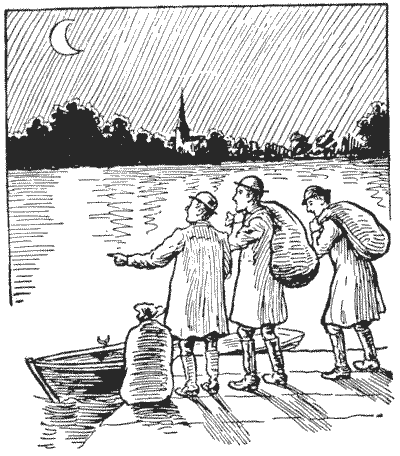

CROSSING THE RIVER AXE

Many years ago, in the days of the smuggler known as "Rob Roy of the West," a piratical band buried on the coast of South Devon a quantity of treasure which was, of course, abandoned by them in the usual inexplicable way. Some time afterwards its whereabouts was discovered by three countrymen, who visited the spot one night and divided the spoil between them, Giles taking treasure to the value of £`800`, Jasper £`500` worth, and Timothy £`300` worth. In returning they had to cross the river Axe at a point where they had left a small boat in readiness. Here, however, was a difficulty they had not anticipated. The boat would only carry two men, or one man and a sack, and they had so little confidence in one another that no person could be left alone on the land or in the boat with more than his share of the spoil, though two persons (being a check on each other) might be left with more than their shares. The puzzle is to show how they got over the river in the fewest possible crossings, taking their treasure with them. No tricks, such as ropes, "flying bridges," currents, swimming, or similar dodges, may be employed.

Sources:Topics:Algebra -> Word Problems Logic -> Reasoning / Logic Combinatorics -> Case Analysis / Checking Cases -> Processes / Procedures

Many years ago, in the days of the smuggler known as "Rob Roy of the West," a piratical band buried on the coast of South Devon a quantity of treasure which was, of course, abandoned by them in the usual inexplicable way. Some time afterwards its whereabouts was discovered by three countrymen, who visited the spot one night and divided the spoil between them, Giles taking treasure to the value of £`800`, Jasper £`500` worth, and Timothy £`300` worth. In returning they had to cross the river Axe at a point where they had left a small boat in readiness. Here, however, was a difficulty they had not anticipated. The boat would only carry two men, or one man and a sack, and they had so little confidence in one another that no person could be left alone on the land or in the boat with more than his share of the spoil, though two persons (being a check on each other) might be left with more than their shares. The puzzle is to show how they got over the river in the fewest possible crossings, taking their treasure with them. No tricks, such as ropes, "flying bridges," currents, swimming, or similar dodges, may be employed.

Sources:Topics:Algebra -> Word Problems Logic -> Reasoning / Logic Combinatorics -> Case Analysis / Checking Cases -> Processes / Procedures- Amusements in Mathematics, Henry Ernest Dudeney Question 374

-

STEALING THE CASTLE TREASURE

The ingenious manner in which a box of treasure, consisting principally of jewels and precious stones, was stolen from Gloomhurst Castle has been handed down as a tradition in the De Gourney family. The thieves consisted of a man, a youth, and a small boy, whose only mode of escape with the box of treasure was by means of a high window. Outside the window was fixed a pulley, over which ran a rope with a basket at each end. When one basket was on the ground the other was at the window. The rope was so disposed that the persons in the basket could neither help themselves by means of it nor receive help from others. In short, the only way the baskets could be used was by placing a heavier weight in one than in the other.

Now, the man weighed `195` lbs., the youth `105` lbs., the boy `90` lbs., and the box of treasure `75` lbs. The weight in the descending basket could not exceed that in the other by more than `15` lbs. without causing a descent so rapid as to be most dangerous to a human being, though it would not injure the stolen property. Only two persons, or one person and the treasure, could be placed in the same basket at one time. How did they all manage to escape and take the box of treasure with them?

The puzzle is to find the shortest way of performing the feat, which in itself is not difficult. Remember, a person cannot help himself by hanging on to the rope, the only way being to go down "with a bump," with the weight in the other basket as a counterpoise.

Sources:Topics:Algebra -> Word Problems Algorithm Theory -> Weighing Combinatorics -> Case Analysis / Checking Cases -> Processes / Procedures Minimum and Maximum Problems / Optimization Problems- Amusements in Mathematics, Henry Ernest Dudeney Question 377

-

THE VILLAGE CRICKET MATCH

In a cricket match, Dingley Dell v. All Muggleton, the latter had the first innings. Mr. Dumkins and Mr. Podder were at the wickets, when the wary Dumkins made a splendid late cut, and Mr. Podder called on him to run. Four runs were apparently completed, but the vigilant umpires at each end called, "three short," making six short runs in all. What number did Mr. Dumkins score? When Dingley Dell took their turn at the wickets their champions were Mr. Luffey and Mr. Struggles. The latter made a magnificent off-drive, and invited his colleague to "come along," with the result that the observant spectators applauded them for what was supposed to have been three sharp runs. But the umpires declared that there had been two short runs at each end—four in all. To what extent, if any, did this manœuvre increase Mr. Struggles's total? Sources:- Amusements in Mathematics, Henry Ernest Dudeney Question 387

-

SLOW CRICKET

In the recent county match between Wessex and Nincomshire the former team were at the wickets all day, the last man being put out a few minutes before the time for drawing stumps. The play was so slow that most of the spectators were fast asleep, and, on being awakened by one of the officials clearing the ground, we learnt that two men had been put out leg-before-wicket for a combined score of `19` runs; four men were caught for a combined score or `17` runs; one man was run out for a duck's egg; and the others were all bowled for `3` runs each. There were no extras. We were not told which of the men was the captain, but he made exactly `15` more than the average of his team. What was the captain's score? Sources:- Amusements in Mathematics, Henry Ernest Dudeney Question 388

-

THE HORSE-RACE PUZZLE

There are no morals in puzzles. When we are solving the old puzzle of the captain who, having to throw half his crew overboard in a storm, arranged to draw lots, but so placed the men that only the Turks were sacrificed, and all the Christians left on board, we do not stop to discuss the questionable morality of the proceeding. And when we are dealing with a measuring problem, in which certain thirsty pilgrims are to make an equitable division of a barrel of beer, we do not object that, as total abstainers, it is against our conscience to have anything to do with intoxicating liquor. Therefore I make no apology for introducing a puzzle that deals with betting.

Three horses—Acorn, Bluebottle, and Capsule—start in a race. The odds are `4` to `1`, Acorn; `3` to `1`, Bluebottle; `2` to `1`, Capsule. Now, how much must I invest on each horse in order to win £`13`, no matter which horse comes in first? Supposing, as an example, that I betted £`5` on each horse. Then, if Acorn won, I should receive £`20` (four times £`5`), and have to pay £`5` each for the other two horses; thereby winning £`10`. But it will be found that if Bluebottle was first I should only win £`5`, and if Capsule won I should gain nothing and lose nothing. This will make the question perfectly clear to the novice, who, like myself, is not interested in the calling of the fraternity who profess to be engaged in the noble task of "improving the breed of horses."

Sources:- Amusements in Mathematics, Henry Ernest Dudeney Question 390

-

THE MOTOR-CAR RACE

Sometimes a quite simple statement of fact, if worded in an unfamiliar manner, will cause considerable perplexity. Here is an example, and it will doubtless puzzle some of my more youthful readers just a little. I happened to be at a motor-car race at Brooklands, when one spectator said to another, while a number of cars were whirling round and round the circular track:—

"There's Gogglesmith—that man in the white car!"

"Yes, I see," was the reply; "but how many cars are running in this race?"

Then came this curious rejoinder:—

"One-third of the cars in front of Gogglesmith added to three-quarters of those behind him will give you the answer."

Now, can you tell how many cars were running in the race?

Sources:- Amusements in Mathematics, Henry Ernest Dudeney Question 391

-

SUCH A GETTING UPSTAIRS

In a suburban villa there is a small staircase with eight steps, not counting the landing. The little puzzle with which Tommy Smart perplexed his family is this. You are required to start from the bottom and land twice on the floor above (stopping there at the finish), having returned once to the ground floor. But you must be careful to use every tread the same number of times. In how few steps can you make the ascent? It seems a very simple matter, but it is more than likely that at your first attempt you will make a great many more steps than are necessary. Of course you must not go more than one riser at a time.

Tommy knows the trick, and has shown it to his father, who professes to have a contempt for such things; but when the children are in bed the pater will often take friends out into the hall and enjoy a good laugh at their bewilderment. And yet it is all so very simple when you know how it is done.

Sources:- Amusements in Mathematics, Henry Ernest Dudeney Question 418

-

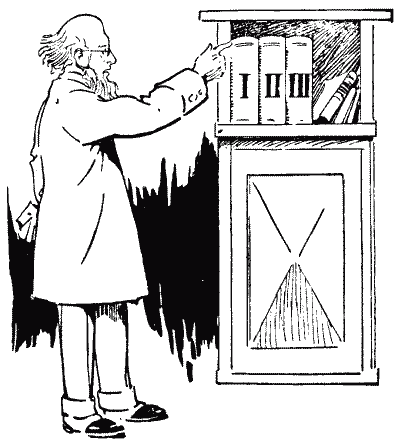

THE INDUSTRIOUS BOOKWORM

Our friend Professor Rackbrane is seen in the illustration to be propounding another of his little posers. He is explaining that since he last had occasion to take down those three volumes of a learned book from their place on his shelves a bookworm has actually bored a hole straight through from the first page to the last. He says that the leaves are together three inches thick in each volume, and that every cover is exactly one-eighth of an inch thick, and he asks how long a tunnel had the industrious worm to bore in preparing his new tube railway. Can you tell him?

Sources:Topics:Algebra -> Word Problems

Our friend Professor Rackbrane is seen in the illustration to be propounding another of his little posers. He is explaining that since he last had occasion to take down those three volumes of a learned book from their place on his shelves a bookworm has actually bored a hole straight through from the first page to the last. He says that the leaves are together three inches thick in each volume, and that every cover is exactly one-eighth of an inch thick, and he asks how long a tunnel had the industrious worm to bore in preparing his new tube railway. Can you tell him?

Sources:Topics:Algebra -> Word Problems- Amusements in Mathematics, Henry Ernest Dudeney Question 420

-

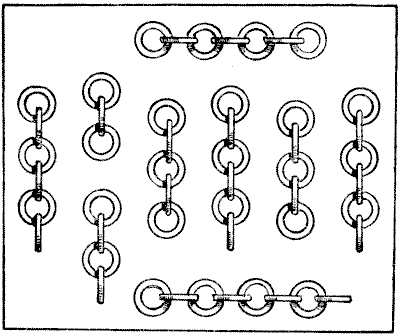

A CHAIN PUZZLE

This is a puzzle based on a pretty little idea first dealt with by the late Mr. Sam Loyd. A man had nine pieces of chain, as shown in the illustration. He wanted to join these fifty links into one endless chain. It will cost a penny to open any link and twopence to weld a link together again, but he could buy a new endless chain of the same character and quality for `2`s. `2`d. What was the cheapest course for him to adopt? Unless the reader is cunning he may find himself a good way out in his answer.

Sources:

This is a puzzle based on a pretty little idea first dealt with by the late Mr. Sam Loyd. A man had nine pieces of chain, as shown in the illustration. He wanted to join these fifty links into one endless chain. It will cost a penny to open any link and twopence to weld a link together again, but he could buy a new endless chain of the same character and quality for `2`s. `2`d. What was the cheapest course for him to adopt? Unless the reader is cunning he may find himself a good way out in his answer.

Sources:

- Amusements in Mathematics, Henry Ernest Dudeney Question 421

-

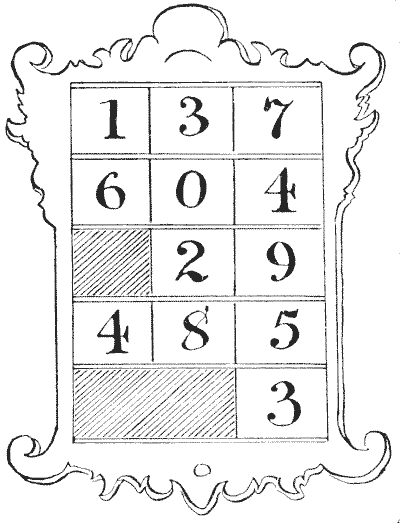

THE HYMN-BOARD POSER

The worthy vicar of Chumpley St. Winifred is in great distress. A little church difficulty has arisen that all the combined intelligence of the parish seems unable to surmount. What this difficulty is I will state hereafter, but it may add to the interest of the problem if I first give a short account of the curious position that has been brought about. It all has to do with the church hymn-boards, the plates of which have become so damaged that they have ceased to fulfil the purpose for which they were devised. A generous parishioner has promised to pay for a new set of plates at a certain rate of cost; but strange as it may seem, no agreement can be come to as to what that cost should be. The proposed maker of the plates has named a price which the donor declares to be absurd. The good vicar thinks they are both wrong, so he asks the schoolmaster to work out the little sum. But this individual declares that he can find no rule bearing on the subject in any of his arithmetic books. An application having been made to the local medical practitioner, as a man of more than average intellect at Chumpley, he has assured the vicar that his practice is so heavy that he has not had time even to look at it, though his assistant whispers that the doctor has been sitting up unusually late for several nights past. Widow Wilson has a smart son, who is reputed to have once won a prize for puzzle-solving. He asserts that as he cannot find any solution to the problem it must have something to do with the squaring of the circle, the duplication of the cube, or the trisection of an angle; at any rate, he has never before seen a puzzle on the principle, and he gives it up.

This was the state of affairs when the assistant curate (who, I should say, had frankly confessed from the first that a profound study of theology had knocked out of his head all the knowledge of mathematics he ever possessed) kindly sent me the puzzle.

A church has three hymn-boards, each to indicate the numbers of five different hymns to be sung at a service. All the boards are in use at the same service. The hymn-book contains `700` hymns. A new set of numbers is required, and a kind parishioner offers to present a set painted on metal plates, but stipulates that only the smallest number of plates necessary shall be purchased. The cost of each plate is to be `6`d., and for the painting of each plate the charges are to be: For one plate, `1`s.; for two plates alike, `11`¾d. each; for three plates alike, `11`½d. each, and so on, the charge being one farthing less per plate for each similarly painted plate. Now, what should be the lowest cost?

Readers will note that they are required to use every legitimate and practical method of economy. The illustration will make clear the nature of the three hymn-boards and plates. The five hymns are here indicated by means of twelve plates. These plates slide in separately at the back, and in the illustration there is room, of course, for three more plates.

Sources:Topics:Arithmetic Algebra -> Word Problems Combinatorics -> Case Analysis / Checking Cases -> Processes / Procedures- Amusements in Mathematics, Henry Ernest Dudeney Question 426