Amusements in Mathematics, Henry Ernest Dudeney

-

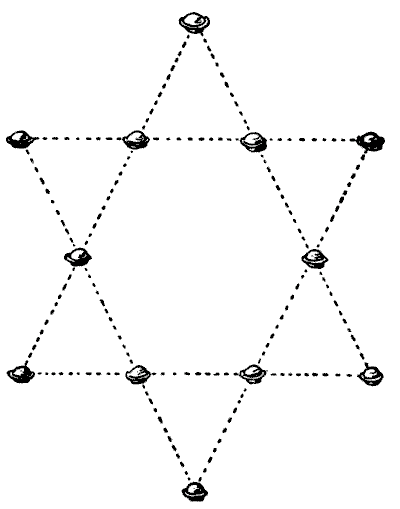

Question 211 - THE TWELVE MINCE-PIES

It will be seen in our illustration how twelve mince-pies may be placed on the table so as to form six straight rows with four pies in every row. The puzzle is to remove only four of them to new positions so that there shall be seven straight rows with four in every row. Which four would you remove, and where would you replace them?

-

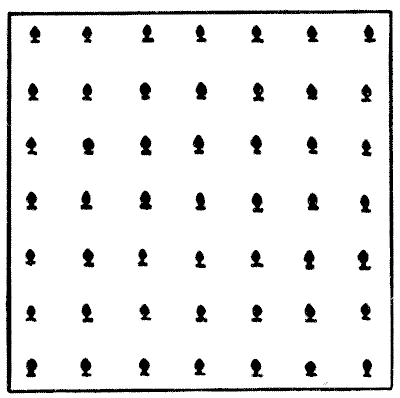

Question 212 - THE BURMESE PLANTATION

A short time ago I received an interesting communication from the British chaplain at Meiktila, Upper Burma, in which my correspondent informed me that he had found some amusement on board ship on his way out in trying to solve this little poser.

If he has a plantation of forty-nine trees, planted in the form of a square as shown in the accompanying illustration, he wishes to know how he may cut down twenty-seven of the trees so that the twenty-two left standing shall form as many rows as possible with four trees in every row.

Of course there may not be more than four trees in any row.

-

Question 213 - TURKS AND RUSSI

This puzzle is on the lines of the Afridi problem published by me in Tit-Bits some years ago.

On an open level tract of country a party of Russian infantry, no two of whom were stationed at the same spot, were suddenly surprised by thirty-two Turks, who opened fire on the Russians from all directions. Each of the Turks simultaneously fired a bullet, and each bullet passed immediately over the heads of three Russian soldiers. As each of these bullets when fired killed a different man, the puzzle is to discover what is the smallest possible number of soldiers of which the Russian party could have consisted and what were the casualties on each side.

Topics:Combinatorics -> Combinatorial Geometry -

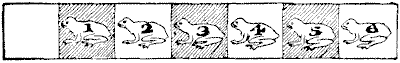

Question 214 - THE SIX FROGS

The six educated frogs in the illustration are trained to reverse their order, so that their numbers shall read `6, 5, 4, 3, 2, 1`, with the blank square in its present position. They can jump to the next square (if vacant) or leap over one frog to the next square beyond (if vacant), just as we move in the game of draughts, and can go backwards or forwards at pleasure. Can you show how they perform their feat in the fewest possible moves? It is quite easy, so when you have done it add a seventh frog to the right and try again. Then add more frogs until you are able to give the shortest solution for any number. For it can always be done, with that single vacant square, no matter how many frogs there are.

Topics:Algebra -> Sequences -> Arithmetic Progression / Arithmetic Sequence

The six educated frogs in the illustration are trained to reverse their order, so that their numbers shall read `6, 5, 4, 3, 2, 1`, with the blank square in its present position. They can jump to the next square (if vacant) or leap over one frog to the next square beyond (if vacant), just as we move in the game of draughts, and can go backwards or forwards at pleasure. Can you show how they perform their feat in the fewest possible moves? It is quite easy, so when you have done it add a seventh frog to the right and try again. Then add more frogs until you are able to give the shortest solution for any number. For it can always be done, with that single vacant square, no matter how many frogs there are.

Topics:Algebra -> Sequences -> Arithmetic Progression / Arithmetic Sequence -

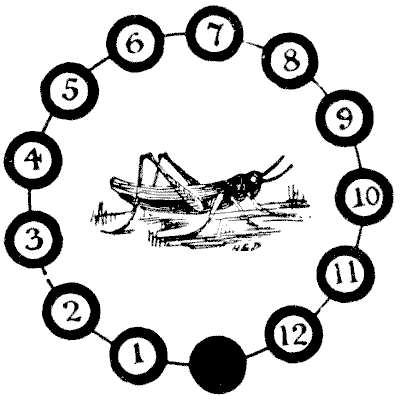

Question 215 - THE GRASSHOPPER PUZZLE

It has been suggested that this puzzle was a great favourite among the young apprentices of the City of London in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries. Readers will have noticed the curious brass grasshopper on the Royal Exchange. This long-lived creature escaped the fires of `1666` and `1838`. The grasshopper, after his kind, was the crest of Sir Thomas Gresham, merchant grocer, who died in `1579`, and from this cause it has been used as a sign by grocers in general. Unfortunately for the legend as to its origin, the puzzle was only produced by myself so late as the year `1900`. On twelve of the thirteen black discs are placed numbered counters or grasshoppers. The puzzle is to reverse their order, so that they shall read, `1, 2, 3, 4`, etc., in the opposite direction, with the vacant disc left in the same position as at present. Move one at a time in any order, either to the adjoining vacant disc or by jumping over one grasshopper, like the moves in draughts. The moves or leaps may be made in either direction that is at any time possible. What are the fewest possible moves in which it can be done?

-

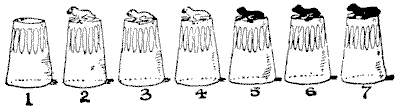

Question 216 - THE EDUCATED FROGS

Our six educated frogs have learnt a new and pretty feat. When placed on glass tumblers, as shown in the illustration, they change sides so that the three black ones are to the left and the white frogs to the right, with the unoccupied tumbler at the opposite end—No. `7`. They can jump to the next tumbler (if unoccupied), or over one, or two, frogs to an unoccupied tumbler. The jumps can be made in either direction, and a frog may jump over his own or the opposite colour, or both colours. Four suecessive specimen jumps will make everything quite plain: `4` to `1, 5` to `4, 3` to `5, 6` to `3`. Can you show how they do it in ten jumps?

Topics:Puzzles and Rebuses

Our six educated frogs have learnt a new and pretty feat. When placed on glass tumblers, as shown in the illustration, they change sides so that the three black ones are to the left and the white frogs to the right, with the unoccupied tumbler at the opposite end—No. `7`. They can jump to the next tumbler (if unoccupied), or over one, or two, frogs to an unoccupied tumbler. The jumps can be made in either direction, and a frog may jump over his own or the opposite colour, or both colours. Four suecessive specimen jumps will make everything quite plain: `4` to `1, 5` to `4, 3` to `5, 6` to `3`. Can you show how they do it in ten jumps?

Topics:Puzzles and Rebuses -

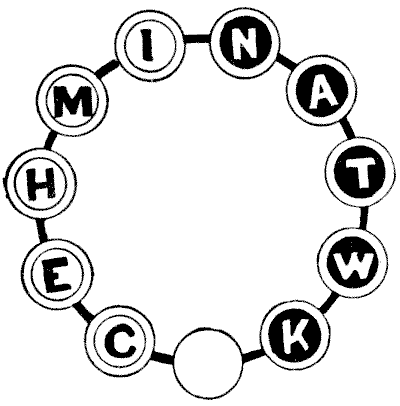

Question 217 - THE TWICKENHAM PUZZLE

In the illustration we have eleven discs in a circle. On five of the discs we place white counters with black letters—as shown—and on five other discs the black counters with white letters. The bottom disc is left vacant. Starting thus, it is required to get the counters into order so that they spell the word "Twickenham" in a clockwise direction, leaving the vacant disc in the original position. The black counters move in the direction that a clock-hand revolves, and the white counters go the opposite way. A counter may jump over one of the opposite colour if the vacant disc is next beyond. Thus, if your first move is with K, then C can jump over K. If then K moves towards E, you may next jump W over C, and so on. The puzzle may be solved in twenty-six moves. Remember a counter cannot jump over one of its own colour.

Topics:Puzzles and Rebuses

In the illustration we have eleven discs in a circle. On five of the discs we place white counters with black letters—as shown—and on five other discs the black counters with white letters. The bottom disc is left vacant. Starting thus, it is required to get the counters into order so that they spell the word "Twickenham" in a clockwise direction, leaving the vacant disc in the original position. The black counters move in the direction that a clock-hand revolves, and the white counters go the opposite way. A counter may jump over one of the opposite colour if the vacant disc is next beyond. Thus, if your first move is with K, then C can jump over K. If then K moves towards E, you may next jump W over C, and so on. The puzzle may be solved in twenty-six moves. Remember a counter cannot jump over one of its own colour.

Topics:Puzzles and Rebuses -

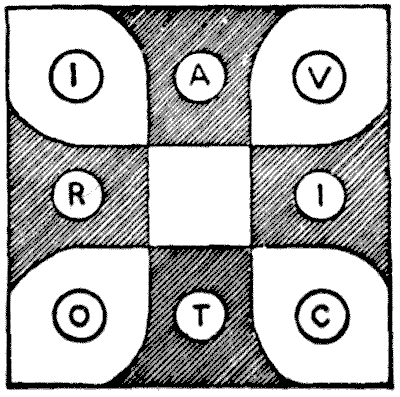

Question 218 - THE VICTORIA CROSS PUZZLE

The puzzle-maker is peculiarly a "snapper-up of unconsidered trifles," and his productions are often built up with the slenderest materials. Trivialities that might entirely escape the observation of others, or, if they were observed, would be regarded as of no possible moment, often supply the man who is in quest of posers with a pretty theme or an idea that he thinks possesses some "basal value."

When seated opposite to a lady in a railway carriage at the time of Queen Victoria's Diamond Jubilee, my attention was attracted to a brooch that she was wearing. It was in the form of a Maltese or Victoria Cross, and bore the letters of the word VICTORIA. The number and arrangement of the letters immediately gave me the suggestion for the puzzle which I now present.

The diagram, it will be seen, is composed of nine divisions. The puzzle is to place eight counters, bearing the letters of the word VICTORIA, exactly in the manner shown, and then slide one letter at a time from black to white and white to black alternately, until the word reads round in the same direction, only with the initial letter V on one of the black arms of the cross. At no time may two letters be in the same division. It is required to find the shortest method.

Leaping moves are, of course, not permitted. The first move must obviously be made with A, I, T, or R. Supposing you move T to the centre, the next counter played will be O or C, since I or R cannot be moved. There is something a little remarkable in the solution of this puzzle which I will explain.

Topics:Puzzles and Rebuses -

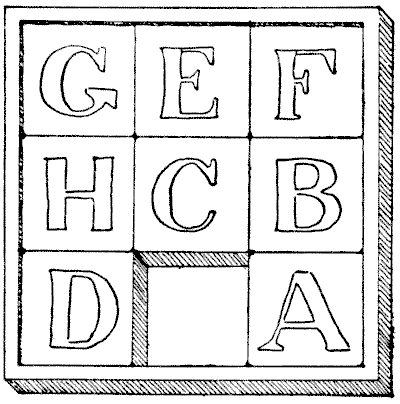

Question 219 - THE LETTER BLOCK PUZZLE

Here is a little reminiscence of our old friend the Fifteen Block Puzzle. Eight wooden blocks are lettered, and are placed in a box, as shown in the illustration. It will be seen that you can only move one block at a time to the place vacant for the time being, as no block may be lifted out of the box. The puzzle is to shift them about until you get them in the order—

A B C

D E F

G HThis you will find by no means difficult if you are allowed as many moves as you like. But the puzzle is to do it in the fewest possible moves. I will not say what this smallest number of moves is, because the reader may like to discover it for himself. In writing down your moves you will find it necessary to record no more than the letters in the order that they are shifted. Thus, your first five moves might be C, H, G, E, F; and this notation can have no possible ambiguity. In practice you only need eight counters and a simple diagram on a sheet of paper.

Topics:Puzzles and Rebuses -

Question 220 - A LODGING-HOUSE DIFFICULTY

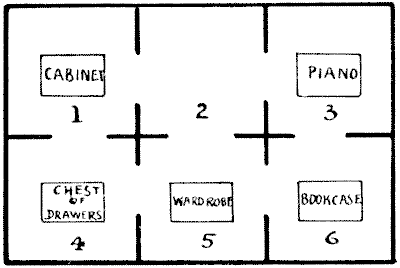

The Dobsons secured apartments at Slocomb-on-Sea. There were six rooms on the same floor, all communicating, as shown in the diagram. The rooms they took were numbers `4, 5`, and `6`, all facing the sea. But a little difficulty arose. Mr. Dobson insisted that the piano and the bookcase should change rooms. This was wily, for the Dobsons were not musical, but they wanted to prevent any one else playing the instrument. Now, the rooms were very small and the pieces of furniture indicated were very big, so that no two of these articles could be got into any room at the same time. How was the exchange to be made with the least possible labour? Suppose, for example, you first move the wardrobe into No. `2`; then you can move the bookcase to No. `5` and the piano to No. `6`, and so on. It is a fascinating puzzle, but the landlady had reasons for not appreciating it. Try to solve her difficulty in the fewest possible removals with counters on a sheet of paper.

The Dobsons secured apartments at Slocomb-on-Sea. There were six rooms on the same floor, all communicating, as shown in the diagram. The rooms they took were numbers `4, 5`, and `6`, all facing the sea. But a little difficulty arose. Mr. Dobson insisted that the piano and the bookcase should change rooms. This was wily, for the Dobsons were not musical, but they wanted to prevent any one else playing the instrument. Now, the rooms were very small and the pieces of furniture indicated were very big, so that no two of these articles could be got into any room at the same time. How was the exchange to be made with the least possible labour? Suppose, for example, you first move the wardrobe into No. `2`; then you can move the bookcase to No. `5` and the piano to No. `6`, and so on. It is a fascinating puzzle, but the landlady had reasons for not appreciating it. Try to solve her difficulty in the fewest possible removals with counters on a sheet of paper.