Puzzles and Rebuses

This is a general category for brain-teasers that require cleverness, lateral thinking, or pattern recognition. Rebuses are word puzzles using pictures, symbols, or letters to represent words or phrases. Math-related versions might involve numerical or operational clues hidden in a visual format.

Matchstick Puzzles Reconstruct the Exercise / Cryptarithmetic-

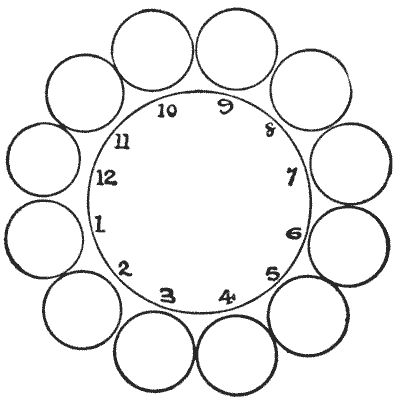

THE TWELVE PENNIES

Here is a pretty little puzzle that only requires twelve pennies or counters. Arrange them in a circle, as shown in the illustration. Now take up one penny at a time and, passing it over two pennies, place it on the third penny. Then take up another single penny and do the same thing, and so on, until, in six such moves, you have the coins in six pairs in the positions `1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6`. You can move in either direction round the circle at every play, and it does not matter whether the two jumped over are separate or a pair. This is quite easy if you use just a little thought. Sources:Topics:Puzzles and Rebuses

Sources:Topics:Puzzles and Rebuses- Amusements in Mathematics, Henry Ernest Dudeney Question 230

-

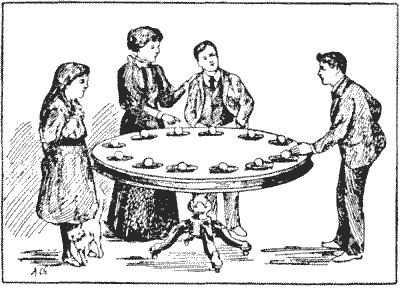

PLATES AND COINS

Place twelve plates, as shown, on a round table, with a penny or orange in every plate. Start from any plate you like and, always going in one direction round the table, take up one penny, pass it over two other pennies, and place it in the next plate. Go on again; take up another penny and, having passed it over two pennies, place it in a plate; and so continue your journey. Six coins only are to be removed, and when these have been placed there should be two coins in each of six plates and six plates empty. An important point of the puzzle is to go round the table as few times as possible. It does not matter whether the two coins passed over are in one or two plates, nor how many empty plates you pass a coin over. But you must always go in one direction round the table and end at the point from which you set out. Your hand, that is to say, goes steadily forward in one direction, without ever moving backwards. Sources:Topics:Puzzles and Rebuses

Sources:Topics:Puzzles and Rebuses- Amusements in Mathematics, Henry Ernest Dudeney Question 231

-

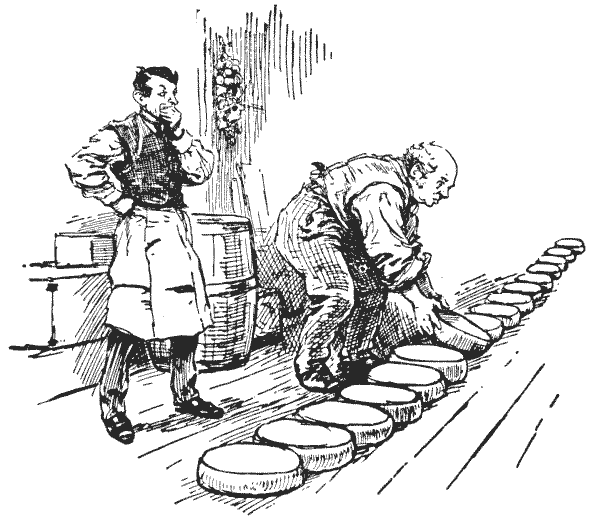

THE ECCENTRIC CHEESEMONGER

The cheesemonger depicted in the illustration is an inveterate puzzle lover. One of his favourite puzzles is the piling of cheeses in his warehouse, an amusement that he finds good exercise for the body as well as for the mind. He places sixteen cheeses on the floor in a straight row and then makes them into four piles, with four cheeses in every pile, by always passing a cheese over four others. If you use sixteen counters and number them in order from `1` to `16`, then you may place `1` on `6, 11` on `1, 7` on `4`, and so on, until there are four in every pile. It will be seen that it does not matter whether the four passed over are standing alone or piled; they count just the same, and you can always carry a cheese in either direction. There are a great many different ways of doing it in twelve moves, so it makes a good game of "patience" to try to solve it so that the four piles shall be left in different stipulated places. For example, try to leave the piles at the extreme ends of the row, on Nos. `1, 2, 15` and `16`; this is quite easy. Then try to leave three piles together, on Nos. `13, 14`, and `15`. Then again play so that they shall be left on Nos. `3, 5, 12`, and `14`.

Sources:Topics:Puzzles and Rebuses

The cheesemonger depicted in the illustration is an inveterate puzzle lover. One of his favourite puzzles is the piling of cheeses in his warehouse, an amusement that he finds good exercise for the body as well as for the mind. He places sixteen cheeses on the floor in a straight row and then makes them into four piles, with four cheeses in every pile, by always passing a cheese over four others. If you use sixteen counters and number them in order from `1` to `16`, then you may place `1` on `6, 11` on `1, 7` on `4`, and so on, until there are four in every pile. It will be seen that it does not matter whether the four passed over are standing alone or piled; they count just the same, and you can always carry a cheese in either direction. There are a great many different ways of doing it in twelve moves, so it makes a good game of "patience" to try to solve it so that the four piles shall be left in different stipulated places. For example, try to leave the piles at the extreme ends of the row, on Nos. `1, 2, 15` and `16`; this is quite easy. Then try to leave three piles together, on Nos. `13, 14`, and `15`. Then again play so that they shall be left on Nos. `3, 5, 12`, and `14`.

Sources:Topics:Puzzles and Rebuses- Amusements in Mathematics, Henry Ernest Dudeney Question 233

-

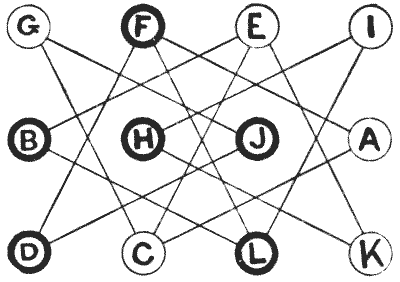

THE EXCHANGE PUZZLE

Here is a rather entertaining little puzzle with moving counters. You only need twelve counters—six of one colour, marked A, C, E, G, I, and K, and the other six marked B, D, F, H, J, and L. You first place them on the diagram, as shown in the illustration, and the puzzle is to get them into regular alphabetical order, as follows:—

A B C D E F G H I J K L The moves are made by exchanges of opposite colours standing on the same line. Thus, G and J may exchange places, or F and A, but you cannot exchange G and C, or F and D, because in one case they are both white and in the other case both black. Can you bring about the required arrangement in seventeen exchanges?

It cannot be done in fewer moves. The puzzle is really much easier than it looks, if properly attacked.

Sources:Topics:Combinatorics -> Invariants Logic -> Reasoning / Logic Combinatorics -> Case Analysis / Checking Cases -> Processes / Procedures Combinatorics -> Case Analysis / Checking Cases -> Processes / Procedures Puzzles and Rebuses- Amusements in Mathematics, Henry Ernest Dudeney Question 234

-

THE HAT PUZZLE

Ten hats were hung on pegs as shown in the illustration—five silk hats and five felt "bowlers," alternately silk and felt. The two pegs at the end of the row were empty.

The puzzle is to remove two contiguous hats to the vacant pegs, then two other adjoining hats to the pegs now unoccupied, and so on until five pairs have been moved and the hats again hang in an unbroken row, but with all the silk ones together and all the felt hats together.

Remember, the two hats removed must always be contiguous ones, and you must take one in each hand and place them on their new pegs without reversing their relative position. You are not allowed to cross your hands, nor to hang up one at a time.

Can you solve this old puzzle, which I give as introductory to the next? Try it with counters of two colours or with coins, and remember that the two empty pegs must be left at one end of the row.

Sources:Topics:Puzzles and Rebuses- Amusements in Mathematics, Henry Ernest Dudeney Question 236

-

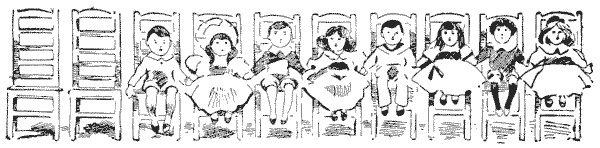

BOYS AND GIRLS

If you mark off ten divisions on a sheet of paper to represent the chairs, and use eight numbered counters for the children, you will have a fascinating pastime. Let the odd numbers represent boys and even numbers girls, or you can use counters of two colours, or coins.

The puzzle is to remove two children who are occupying adjoining chairs and place them in two empty chairs, making them first change sides; then remove a second pair of children from adjoining chairs and place them in the two now vacant, making them change sides; and so on, until all the boys are together and all the girls together, with the two vacant chairs at one end as at present. To solve the puzzle you must do this in five moves. The two children must always be taken from chairs that are next to one another; and remember the important point of making the two children change sides, as this latter is the distinctive feature of the puzzle. By "change sides" I simply mean that if, for example, you first move `1` and `2` to the vacant chairs, then the first (the outside) chair will be occupied by `2` and the second one by `1`.

Sources:

- Amusements in Mathematics, Henry Ernest Dudeney Question 237

-

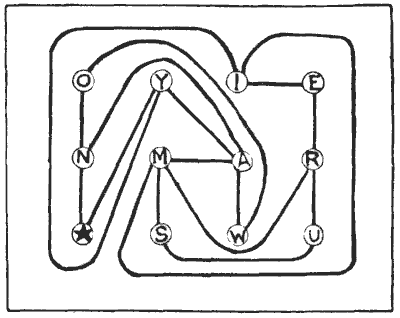

THE CYCLISTS' TOUR

Two cyclists were consulting a road map in preparation for a little tour together. The circles represent towns, and all the good roads are represented by lines. They are starting from the town with a star, and must complete their tour at E. But before arriving there they want to visit every other town once, and only once. That is the difficulty. Mr. Spicer said, "I am certain we can find a way of doing it;" but Mr. Maggs replied, "No way, I'm sure." Now, which of them was correct? Take your pencil and see if you can find any way of doing it. Of course you must keep to the roads indicated. Sources:

Sources:

- Amusements in Mathematics, Henry Ernest Dudeney Question 248

-

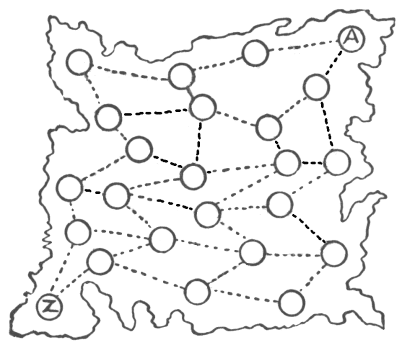

THE GRAND TOUR

One of the everyday puzzles of life is the working out of routes. If you are taking a holiday on your bicycle, or a motor tour, there always arises the question of how you are to make the best of your time and other resources. You have determined to get as far as some particular place, to include visits to such-and-such a town, to try to see something of special interest elsewhere, and perhaps to try to look up an old friend at a spot that will not take you much out of your way. Then you have to plan your route so as to avoid bad roads, uninteresting country, and, if possible, the necessity of a return by the same way that you went. With a map before you, the interesting puzzle is attacked and solved. I will present a little poser based on these lines.

I give a rough map of a country—it is not necessary to say what particular country—the circles representing towns and the dotted lines the railways connecting them. Now there lived in the town marked A a man who was born there, and during the whole of his life had never once left his native place. From his youth upwards he had been very industrious, sticking incessantly to his trade, and had no desire whatever to roam abroad. However, on attaining his fiftieth birthday he decided to see something of his country, and especially to pay a visit to a very old friend living at the town marked Z. What he proposed was this: that he would start from his home, enter every town once and only once, and finish his journey at Z. As he made up his mind to perform this grand tour by rail only, he found it rather a puzzle to work out his route, but he at length succeeded in doing so. How did he manage it? Do not forget that every town has to be visited once, and not more than once.

Sources:Topics:Combinatorics -> Combinatorial Geometry Combinatorics -> Graph Theory Logic -> Reasoning / Logic Combinatorics -> Case Analysis / Checking Cases -> Processes / Procedures Puzzles and Rebuses

Sources:Topics:Combinatorics -> Combinatorial Geometry Combinatorics -> Graph Theory Logic -> Reasoning / Logic Combinatorics -> Case Analysis / Checking Cases -> Processes / Procedures Puzzles and Rebuses- Amusements in Mathematics, Henry Ernest Dudeney Question 250

-

THE HONEYCOMB PUZZLE

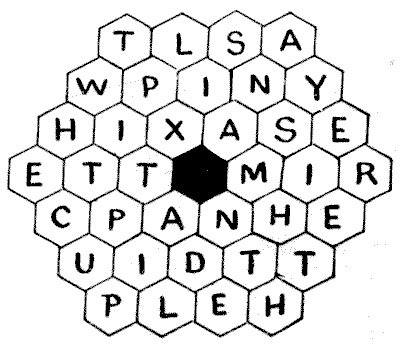

Here is a little puzzle with the simplest possible conditions. Place the point of your pencil on a letter in one of the cells of the honeycomb, and trace out a very familiar proverb by passing always from a cell to one that is contiguous to it. If you take the right route you will have visited every cell once, and only once. The puzzle is much easier than it looks.

Sources:Topics:Puzzles and Rebuses

Here is a little puzzle with the simplest possible conditions. Place the point of your pencil on a letter in one of the cells of the honeycomb, and trace out a very familiar proverb by passing always from a cell to one that is contiguous to it. If you take the right route you will have visited every cell once, and only once. The puzzle is much easier than it looks.

Sources:Topics:Puzzles and Rebuses- Amusements in Mathematics, Henry Ernest Dudeney Question 260

-

THOSE FIFTEEN SHEEP

A certain cyclopædia has the following curious problem, I am told: "Place fifteen sheep in four pens so that there shall be the same number of sheep in each pen." No answer whatever is vouchsafed, so I thought I would investigate the matter. I saw that in dealing with apples or bricks the thing would appear to be quite impossible, since four times any number must be an even number, while fifteen is an odd number. I thought, therefore, that there must be some quality peculiar to the sheep that was not generally known. So I decided to interview some farmers on the subject. The first one pointed out that if we put one pen inside another, like the rings of a target, and placed all sheep in the smallest pen, it would be all right. But I objected to this, because you admittedly place all the sheep in one pen, not in four pens. The second man said that if I placed four sheep in each of three pens and three sheep in the last pen (that is fifteen sheep in all), and one of the ewes in the last pen had a lamb during the night, there would be the same number in each pen in the morning. This also failed to satisfy me. The third farmer said, "I've got four hurdle pens down in one of my fields, and a small flock of wethers, so if you will just step down with me I will show you how it is done." The illustration depicts my friend as he is about to demonstrate the matter to me. His lucid explanation was evidently that which was in the mind of the writer of the article in the cyclopædia. What was it? Can you place those fifteen sheep?

Sources:Topics:Algebra -> Word Problems Logic -> Reasoning / Logic Combinatorics -> Case Analysis / Checking Cases -> Processes / Procedures Puzzles and Rebuses

The third farmer said, "I've got four hurdle pens down in one of my fields, and a small flock of wethers, so if you will just step down with me I will show you how it is done." The illustration depicts my friend as he is about to demonstrate the matter to me. His lucid explanation was evidently that which was in the mind of the writer of the article in the cyclopædia. What was it? Can you place those fifteen sheep?

Sources:Topics:Algebra -> Word Problems Logic -> Reasoning / Logic Combinatorics -> Case Analysis / Checking Cases -> Processes / Procedures Puzzles and Rebuses- Amusements in Mathematics, Henry Ernest Dudeney Question 262