Puzzles and Rebuses

This is a general category for brain-teasers that require cleverness, lateral thinking, or pattern recognition. Rebuses are word puzzles using pictures, symbols, or letters to represent words or phrases. Math-related versions might involve numerical or operational clues hidden in a visual format.

Matchstick Puzzles Reconstruct the Exercise / Cryptarithmetic-

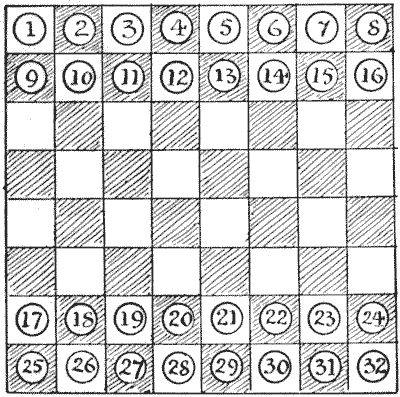

CHESSBOARD SOLITAIRE

Here is an extension of the last game of solitaire. All you need is a chessboard and the thirty-two pieces, or the same number of draughts or counters. In the illustration numbered counters are used. The puzzle is to remove all the counters except two, and these two must have originally been on the same side of the board; that is, the two left must either belong to the group `1` to `16` or to the other group, `17` to `32`. You remove a counter by jumping over it with another counter to the next square beyond, if that square is vacant, but you cannot make a leap in a diagonal direction. The following moves will make the play quite clear: `3-11`, `4-12`, `3-4`, `13-3`. Here `3` jumps over `11`, and you remove `11`; `4` jumps over `12`, and you remove `12`; and so on. It will be found a fascinating little game of patience, and the solution requires the exercise of some ingenuity.

Sources:Topics:Combinatorics -> Game Theory Logic -> Reasoning / Logic Combinatorics -> Case Analysis / Checking Cases -> Processes / Procedures Puzzles and Rebuses

Here is an extension of the last game of solitaire. All you need is a chessboard and the thirty-two pieces, or the same number of draughts or counters. In the illustration numbered counters are used. The puzzle is to remove all the counters except two, and these two must have originally been on the same side of the board; that is, the two left must either belong to the group `1` to `16` or to the other group, `17` to `32`. You remove a counter by jumping over it with another counter to the next square beyond, if that square is vacant, but you cannot make a leap in a diagonal direction. The following moves will make the play quite clear: `3-11`, `4-12`, `3-4`, `13-3`. Here `3` jumps over `11`, and you remove `11`; `4` jumps over `12`, and you remove `12`; and so on. It will be found a fascinating little game of patience, and the solution requires the exercise of some ingenuity.

Sources:Topics:Combinatorics -> Game Theory Logic -> Reasoning / Logic Combinatorics -> Case Analysis / Checking Cases -> Processes / Procedures Puzzles and Rebuses- Amusements in Mathematics, Henry Ernest Dudeney Question 360

-

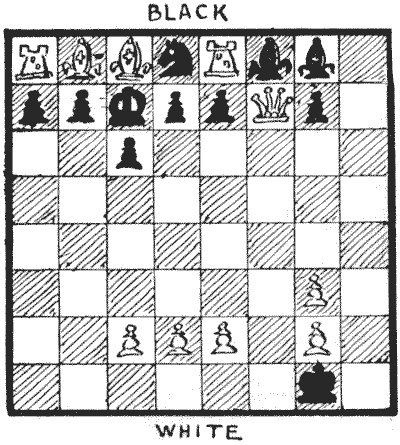

THE MONSTROSITY

One Christmas Eve I was travelling by rail to a little place in one of the southern counties. The compartment was very full, and the passengers were wedged in very tightly. My neighbour in one of the corner seats was closely studying a position set up on one of those little folding chessboards that can be carried conveniently in the pocket, and I could scarcely avoid looking at it myself. Here is the position:—

My fellow-passenger suddenly turned his head and caught the look of bewilderment on my face.

"Do you play chess?" he asked.

"Yes, a little. What is that? A problem?"

"Problem? No; a game."

"Impossible!" I exclaimed rather rudely. "The position is a perfect monstrosity!"

He took from his pocket a postcard and handed it to me. It bore an address at one side and on the other the words "`43`. K to Kt `8`."

"It is a correspondence game." he exclaimed. "That is my friend's last move, and I am considering my reply."

"But you really must excuse me; the position seems utterly impossible. How on earth, for example—"

"Ah!" he broke in smilingly. "I see; you are a beginner; you play to win."

"Of course you wouldn't play to lose or draw!"

He laughed aloud."You have much to learn. My friend and myself do not play for results of that antiquated kind. We seek in chess the wonderful, the whimsical, the weird. Did you ever see a position like that?"

I inwardly congratulated myself that I never had.

"That position, sir, materializes the sinuous evolvements and syncretic, synthetic, and synchronous concatenations of two cerebral individualities. It is the product of an amphoteric and intercalatory interchange of—"

"Have you seen the evening paper, sir?" interrupted the man opposite, holding out a newspaper. I noticed on the margin beside his thumb some pencilled writing. Thanking him, I took the paper and read—"Insane, but quite harmless. He is in my charge."

After that I let the poor fellow run on in his wild way until both got out at the next station.

But that queer position became fixed indelibly in my mind, with Black's last move `43`. K to Kt `8`; and a short time afterwards I found it actually possible to arrive at such a position in forty-three moves. Can the reader construct such a sequence? How did White get his rooks and king's bishop into their present positions, considering Black can never have moved his king's bishop? No odds were given, and every move was perfectly legitimate.

Sources:- Amusements in Mathematics, Henry Ernest Dudeney Question 361

-

THE FOUR ELOPEMENTS

Colonel B—— was a widower of a very taciturn disposition. His treatment of his four daughters was unusually severe, almost cruel, and they not unnaturally felt disposed to resent it. Being charming girls with every virtue and many accomplishments, it is not surprising that each had a fond admirer. But the father forbade the young men to call at his house, intercepted all letters, and placed his daughters under stricter supervision than ever. But love, which scorns locks and keys and garden walls, was equal to the occasion, and the four youths conspired together and planned a general elopement.

At the foot of the tennis lawn at the bottom of the garden ran the silver Thames, and one night, after the four girls had been safely conducted from a dormitory window to terra firma, they all crept softly down to the bank of the river, where a small boat belonging to the Colonel was moored. With this they proposed to cross to the opposite side and make their way to a lane where conveyances were waiting to carry them in their flight. Alas! here at the water's brink their difficulties already began.

The young men were so extremely jealous that not one of them would allow his prospective bride to remain at any time in the company of another man, or men, unless he himself were present also. Now, the boat would only hold two persons, though it could, of course, be rowed by one, and it seemed impossible that the four couples would ever get across. But midway in the stream was a small island, and this seemed to present a way out of the difficulty, because a person or persons could be left there while the boat was rowed back or to the opposite shore. If they had been prepared for their difficulty they could have easily worked out a solution to the little poser at any other time. But they were now so hurried and excited in their flight that the confusion they soon got into was exceedingly amusing—or would have been to any one except themselves.

As a consequence they took twice as long and crossed the river twice as often as was really necessary. Meanwhile, the Colonel, who was a very light sleeper, thought he heard a splash of oars. He quickly raised the alarm among his household, and the young ladies were found to be missing. Somebody was sent to the police-station, and a number of officers soon aided in the pursuit of the fugitives, who, in consequence of that delay in crossing the river, were quickly overtaken. The four girls returned sadly to their homes, and afterwards broke off their engagements in disgust.

For a considerable time it was a mystery how the party of eight managed to cross the river in that little boat without any girl being ever left with a man, unless her betrothed was also present. The favourite method is to take eight counters or pieces of cardboard and mark them A, B, C, D, a, b, c, d, to represent the four men and their prospective brides, and carry them from one side of a table to the other in a matchbox (to represent the boat), a penny being placed in the middle of the table as the island.

Readers are now asked to find the quickest method of getting the party across the river. How many passages are necessary from land to land? By "land" is understood either shore or island. Though the boat would not necessarily call at the island every time of crossing, the possibility of its doing so must be provided for. For example, it would not do for a man to be alone in the boat (though it were understood that he intended merely to cross from one bank to the opposite one) if there happened to be a girl alone on the island other than the one to whom he was engaged.

Sources:Topics:Logic -> Reasoning / Logic Combinatorics -> Case Analysis / Checking Cases -> Processes / Procedures Combinatorics -> Case Analysis / Checking Cases -> Processes / Procedures Puzzles and Rebuses- Amusements in Mathematics, Henry Ernest Dudeney Question 376

-

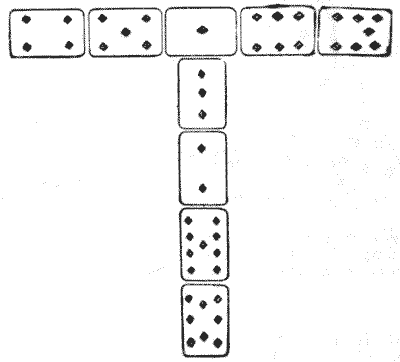

THE "T" CARD PUZZLE

An entertaining little puzzle with cards is to take the nine cards of a suit, from ace to nine inclusive, and arrange them in the form of the letter "T," as shown in the illustration, so that the pips in the horizontal line shall count the same as those in the column. In the example given they add up twenty-three both ways. Now, it is quite easy to get a single correct arrangement. The puzzle is to discover in just how many different ways it may be done. Though the number is high, the solution is not really difficult if we attack the puzzle in the right manner. The reverse way obtained by reflecting the illustration in a mirror we will not count as different, but all other changes in the relative positions of the cards will here count. How many different ways are there?

Sources:Topics:Combinatorics -> Case Analysis / Checking Cases -> Processes / Procedures Puzzles and Rebuses

An entertaining little puzzle with cards is to take the nine cards of a suit, from ace to nine inclusive, and arrange them in the form of the letter "T," as shown in the illustration, so that the pips in the horizontal line shall count the same as those in the column. In the example given they add up twenty-three both ways. Now, it is quite easy to get a single correct arrangement. The puzzle is to discover in just how many different ways it may be done. Though the number is high, the solution is not really difficult if we attack the puzzle in the right manner. The reverse way obtained by reflecting the illustration in a mirror we will not count as different, but all other changes in the relative positions of the cards will here count. How many different ways are there?

Sources:Topics:Combinatorics -> Case Analysis / Checking Cases -> Processes / Procedures Puzzles and Rebuses- Amusements in Mathematics, Henry Ernest Dudeney Question 383

-

"STRAND" PATIENCE

The idea for this came to me when considering the game of Patience that I gave in the Strand Magazine for December, `1910`, which has been reprinted in Ernest Bergholt's Second Book of Patience Games, under the new name of "King Albert."

Make two piles of cards as follows: `9` D, `8` S, `7` D, `6` S, `5` D, `4` S, `3` D, `2` S, `1` D, and `9` H, `8` C, `7` H, `6` C, `5` H, `4` C, `3` H, `2` C, `1` H, with the `9` of diamonds at the bottom of one pile and the `9` of hearts at the bottom of the other. The point is to exchange the spades with the clubs, so that the diamonds and clubs are still in numerical order in one pile and the hearts and spades in the other. There are four vacant spaces in addition to the two spaces occupied by the piles, and any card may be laid on a space, but a card can only be laid on another of the next higher value—an ace on a two, a two on a three, and so on. Patience is required to discover the shortest way of doing this. When there are four vacant spaces you can pile four cards in seven moves, with only three spaces you can pile them in nine moves, and with two spaces you cannot pile more than two cards. When you have a grasp of these and similar facts you will be able to remove a number of cards bodily and write down `7, 9`, or whatever the number of moves may be. The gradual shortening of play is fascinating, and first attempts are surprisingly lengthy.

Sources:Topics:Logic -> Reasoning / Logic Combinatorics -> Case Analysis / Checking Cases -> Processes / Procedures Combinatorics -> Case Analysis / Checking Cases -> Processes / Procedures Puzzles and Rebuses- Amusements in Mathematics, Henry Ernest Dudeney Question 385

-

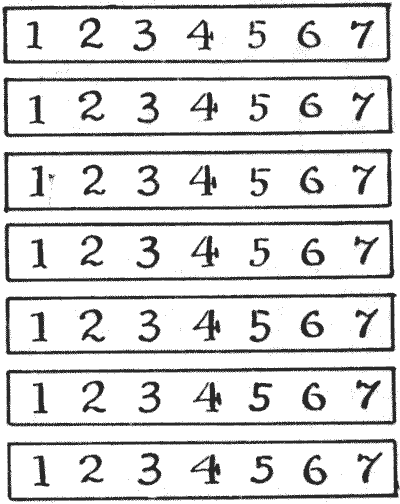

THE MAGIC STRIPS

I happened to have lying on my table a number of strips of cardboard, with numbers printed on them from `1` upwards in numerical order. The idea suddenly came to me, as ideas have a way of unexpectedly coming, to make a little puzzle of this. I wonder whether many readers will arrive at the same solution that I did.

Take seven strips of cardboard and lay them together as above. Then write on each of them the numbers `1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7`, as shown, so that the numbers shall form seven rows and seven columns.

Now, the puzzle is to cut these strips into the fewest possible pieces so that they may be placed together and form a magic square, the seven rows, seven columns, and two diagonals adding up the same number. No figures may be turned upside down or placed on their sides—that is, all the strips must lie in their original direction.

Of course you could cut each strip into seven separate pieces, each piece containing a number, and the puzzle would then be very easy, but I need hardly say that forty-nine pieces is a long way from being the fewest possible.

Sources:- Amusements in Mathematics, Henry Ernest Dudeney Question 400

-

EIGHT JOLLY GAOL BIRDS

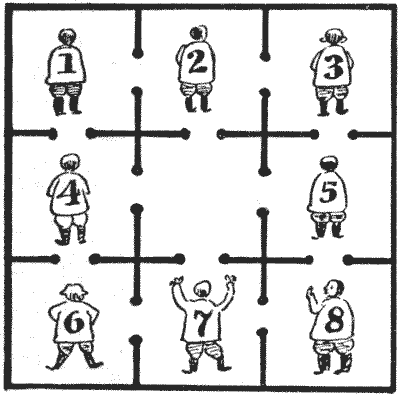

The illustration shows the plan of a prison of nine cells all communicating with one another by doorways. The eight prisoners have their numbers on their backs, and any one of them is allowed to exercise himself in whichever cell may happen to be vacant, subject to the rule that at no time shall two prisoners be in the same cell. The merry monarch in whose dominions the prison was situated offered them special comforts one Christmas Eve if, without breaking that rule, they could so place themselves that their numbers should form a magic square.

Now, prisoner No. `7` happened to know a good deal about magic squares, so he worked out a scheme and naturally selected the method that was most expeditious—that is, one involving the fewest possible moves from cell to cell. But one man was a surly, obstinate fellow (quite unfit for the society of his jovial companions), and he refused to move out of his cell or take any part in the proceedings. But No. `7` was quite equal to the emergency, and found that he could still do what was required in the fewest possible moves without troubling the brute to leave his cell. The puzzle is to show how he did it and, incidentally, to discover which prisoner was so stupidly obstinate. Can you find the fellow?

Sources:- Amusements in Mathematics, Henry Ernest Dudeney Question 401

-

THE EIGHTEEN DOMINOES

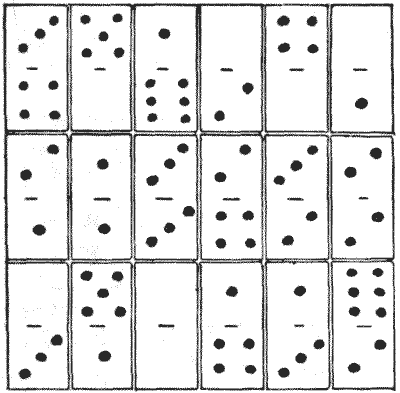

The illustration shows eighteen dominoes arranged in the form of a square so that the pips in every one of the six columns, six rows, and two long diagonals add up `13`. This is the smallest summation possible with any selection of dominoes from an ordinary box of twenty-eight. The greatest possible summation is `23`, and a solution for this number may be easily obtained by substituting for every number its complement to `6`. Thus for every blank substitute a `6`, for every `1` a `5`, for every `2` a `4`, for `3` a `3`, for `4` a `2`, for `5` a `1`, and for `6` a blank. But the puzzle is to make a selection of eighteen dominoes and arrange them (in exactly the form shown) so that the summations shall be `18` in all the fourteen directions mentioned.

Sources:Topics:Puzzles and Rebuses

Sources:Topics:Puzzles and Rebuses- Amusements in Mathematics, Henry Ernest Dudeney Question 406

-

THE MANDARIN'S "T" PUZZLE

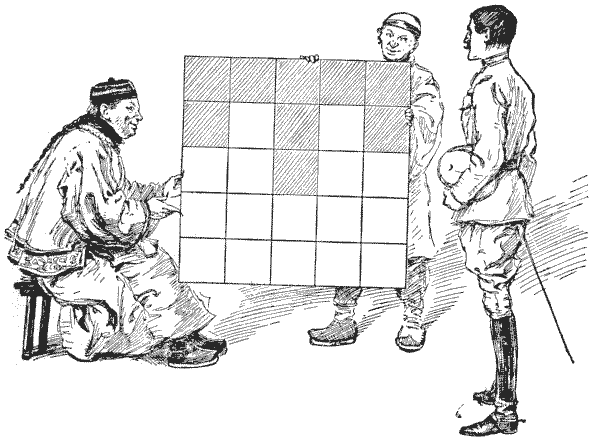

Before Mr. Beauchamp Cholmondely Marjoribanks set out on his tour in the Far East, he prided himself on his knowledge of magic squares, a subject that he had made his special hobby; but he soon discovered that he had never really touched more than the fringe of the subject, and that the wily Chinee could beat him easily. I present a little problem that one learned mandarin propounded to our traveller, as depicted on the last page.

The Chinaman, after remarking that the construction of the ordinary magic square of twenty-five cells is "too velly muchee easy," asked our countryman so to place the numbers `1` to `25` in the square that every column, every row, and each of the two diagonals should add up `65`, with only prime numbers on the shaded "T." Of course the prime numbers available are `1, 2, 3, 5, 7, 11, 13, 17, 19`, and `23`, so you are at liberty to select any nine of these that will serve your purpose. Can you construct this curious little magic square?

Sources:- Amusements in Mathematics, Henry Ernest Dudeney Question 410

-

THE SABBATH PUZZLE

I have come across the following little poser in an old book. I wonder how many readers will see the author's intended solution to the riddle.

Christians the week's first day for Sabbath hold;

Sources:

The Jews the seventh, as they did of old;

The Turks the sixth, as we have oft been told.

How can these three, in the same place and day,

Have each his own true Sabbath? tell, I pray.- Amusements in Mathematics, Henry Ernest Dudeney Question 422