Puzzles and Rebuses

This is a general category for brain-teasers that require cleverness, lateral thinking, or pattern recognition. Rebuses are word puzzles using pictures, symbols, or letters to represent words or phrases. Math-related versions might involve numerical or operational clues hidden in a visual format.

Matchstick Puzzles Reconstruct the Exercise / Cryptarithmetic-

THE BOARD IN COMPARTMENTS

We cannot divide the ordinary chessboard into four equal square compartments, and describe a complete tour, or even path, in each compartment. But we may divide it into four compartments, as in the illustration, two containing each twenty squares, and the other two each twelve squares, and so obtain an interesting puzzle. You are asked to describe a complete re-entrant tour on this board, starting where you like, but visiting every square in each successive compartment before passing into another one, and making the final leap back to the square from which the knight set out. It is not difficult, but will be found very entertaining and not uninstructive.

Whether a re-entrant "tour" or a complete knight's "path" is possible or not on a rectangular board of given dimensions depends not only on its dimensions, but also on its shape. A tour is obviously not possible on a board containing an odd number of cells, such as `5` by `5` or `7` by `7`, for this reason: Every successive leap of the knight must be from a white square to a black and a black to a white alternately. But if there be an odd number of cells or squares there must be one more square of one colour than of the other, therefore the path must begin from a square of the colour that is in excess, and end on a similar colour, and as a knight's move from one colour to a similar colour is impossible the path cannot be re-entrant. But a perfect tour may be made on a rectangular board of any dimensions provided the number of squares be even, and that the number of squares on one side be not less than `6` and on the other not less than `5`. In other words, the smallest rectangular board on which a re-entrant tour is possible is one that is `6` by `5`.

A complete knight's path (not re-entrant) over all the squares of a board is never possible if there be only two squares on one side; nor is it possible on a square board of smaller dimensions than `5` by `5`. So that on a board `4` by `4` we can neither describe a knight's tour nor a complete knight's path; we must leave one square unvisited. Yet on a board `4` by `3` (containing four squares fewer) a complete path may be described in sixteen different ways. It may interest the reader to discover all these. Every path that starts from and ends at different squares is here counted as a different solution, and even reverse routes are called different.

Sources:- Amusements in Mathematics, Henry Ernest Dudeney Question 338

-

THE CUBIC KNIGHT'S TOUR

Some few years ago I happened to read somewhere that Abnit Vandermonde, a clever mathematician, who was born in `1736` and died in `1793`, had devoted a good deal of study to the question of knight's tours. Beyond what may be gathered from a few fragmentary references, I am not aware of the exact nature or results of his investigations, but one thing attracted my attention, and that was the statement that he had proposed the question of a tour of the knight over the six surfaces of a cube, each surface being a chessboard. Whether he obtained a solution or not I do not know, but I have never seen one published. So I at once set to work to master this interesting problem. Perhaps the reader may like to attempt it. Sources:- Amusements in Mathematics, Henry Ernest Dudeney Question 340

-

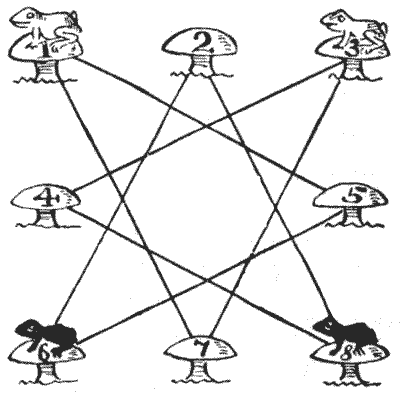

THE FOUR FROGS

In the illustration we have eight toadstools, with white frogs on `1` and `3` and black frogs on `6` and `8`. The puzzle is to move one frog at a time, in any order, along one of the straight lines from toadstool to toadstool, until they have exchanged places, the white frogs being left on `6` and `8` and the black ones on `1` and `3`. If you use four counters on a simple diagram, you will find this quite easy, but it is a little more puzzling to do it in only seven plays, any number of successive moves by one frog counting as one play. Of course, more than one frog cannot be on a toadstool at the same time.

Sources:

In the illustration we have eight toadstools, with white frogs on `1` and `3` and black frogs on `6` and `8`. The puzzle is to move one frog at a time, in any order, along one of the straight lines from toadstool to toadstool, until they have exchanged places, the white frogs being left on `6` and `8` and the black ones on `1` and `3`. If you use four counters on a simple diagram, you will find this quite easy, but it is a little more puzzling to do it in only seven plays, any number of successive moves by one frog counting as one play. Of course, more than one frog cannot be on a toadstool at the same time.

Sources:

- Amusements in Mathematics, Henry Ernest Dudeney Question 341

-

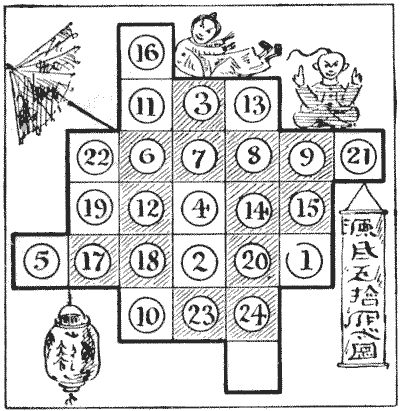

THE MANDARIN'S PUZZLE

The following puzzle has an added interest from the circumstance that a correct solution of it secured for a certain young Chinaman the hand of his charming bride. The wealthiest mandarin within a radius of a hundred miles of Peking was Hi-Chum-Chop, and his beautiful daughter, Peeky-Bo, had innumerable admirers. One of her most ardent lovers was Winky-Hi, and when he asked the old mandarin for his consent to their marriage, Hi-Chum-Chop presented him with the following puzzle and promised his consent if the youth brought him the correct answer within a week. Winky-Hi, following a habit which obtains among certain solvers to this day, gave it to all his friends, and when he had compared their solutions he handed in the best one as his own. Luckily it was quite right. The mandarin thereupon fulfilled his promise. The fatted pup was killed for the wedding feast, and when Hi-Chum-Chop passed Winky-Hi the liver wing all present knew that it was a token of eternal goodwill, in accordance with Chinese custom from time immemorial.

The mandarin had a table divided into twenty-five squares, as shown in the diagram. On each of twenty-four of these squares was placed a numbered counter, just as I have indicated. The puzzle is to get the counters in numerical order by moving them one at a time in what we call "knight's moves." Counter `1` should be where `16` is, `2` where `11` is, `4` where `13` now is, and so on. It will be seen that all the counters on shaded squares are in their proper positions. Of course, two counters may never be on a square at the same time. Can you perform the feat in the fewest possible moves?

In order to make the manner of moving perfectly clear I will point out that the first knight's move can only be made by `1` or by `2` or by `10`. Supposing `1` moves, then the next move must be by `23, 4, 8`, or `21`. As there is never more than one square vacant, the order in which the counters move may be written out as follows: `1`—`21`—`14`—`18`—`22`, etc. A rough diagram should be made on a larger scale for practice, and numbered counters or pieces of cardboard used.

Sources:Topics:Puzzles and Rebuses- Amusements in Mathematics, Henry Ernest Dudeney Question 342

-

STALEMATE

Some years ago the puzzle was proposed to construct an imaginary game of chess, in which White shall be stalemated in the fewest possible moves with all the thirty-two pieces on the board. Can you build up such a position in fewer than twenty moves? Sources:- Amusements in Mathematics, Henry Ernest Dudeney Question 349

-

THE CRUSADER

The following is a prize puzzle propounded by me some years ago. Produce a game of chess which, after sixteen moves, shall leave White with all his sixteen men on their original squares and Black in possession of his king alone (not necessarily on his own square). White is then to force mate in three moves. Sources:- Amusements in Mathematics, Henry Ernest Dudeney Question 351

-

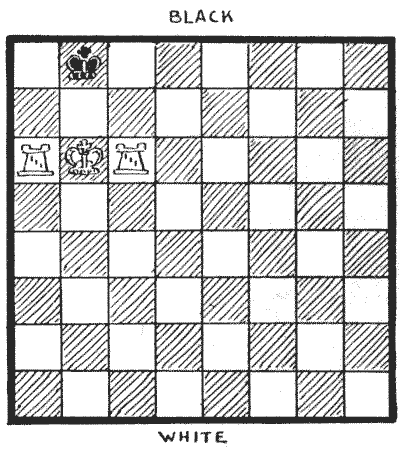

AN AMAZING DILEMMA

In a game of chess between Mr. Black and Mr. White, Black was in difficulties, and as usual was obliged to catch a train. So he proposed that White should complete the game in his absence on condition that no moves whatever should be made for Black, but only with the White pieces. Mr. White accepted, but to his dismay found it utterly impossible to win the game under such conditions. Try as he would, he could not checkmate his opponent. On which square did Mr. Black leave his king? The other pieces are in their proper positions in the diagram. White may leave Black in check as often as he likes, for it makes no difference, as he can never arrive at a checkmate position. Sources:

Sources:

- Amusements in Mathematics, Henry Ernest Dudeney Question 354

-

QUEER CHESS

Can you place two White rooks and a White knight on the board so that the Black king (who must be on one of the four squares in the middle of the board) shall be in check with no possible move open to him? "In other words," the reader will say, "the king is to be shown checkmated." Well, you can use the term if you wish, though I intentionally do not employ it myself. The mere fact that there is no White king on the board would be a sufficient reason for my not doing so. Sources:- Amusements in Mathematics, Henry Ernest Dudeney Question 356

-

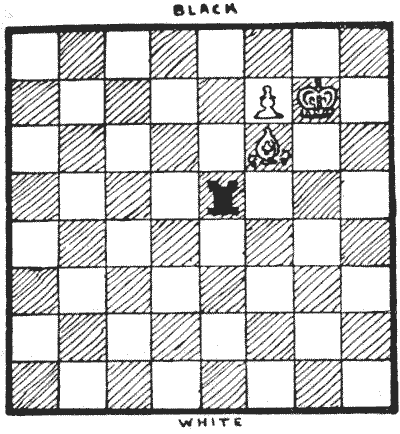

ANCIENT CHINESE PUZZLE

My next puzzle is supposed to be Chinese, many hundreds of years old, and never fails to interest. White to play and mate, moving each of the three pieces once, and once only.

Sources:

My next puzzle is supposed to be Chinese, many hundreds of years old, and never fails to interest. White to play and mate, moving each of the three pieces once, and once only.

Sources:

- Amusements in Mathematics, Henry Ernest Dudeney Question 357

-

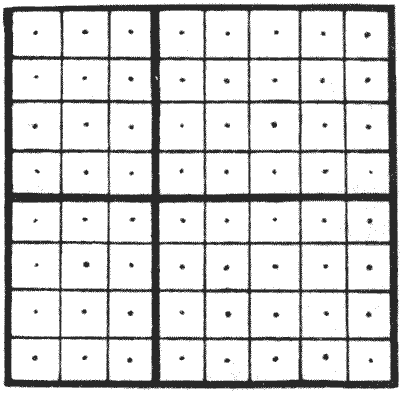

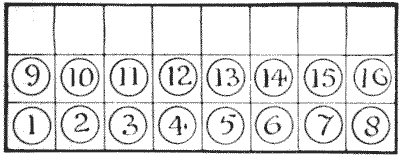

COUNTER SOLITAIRE

Here is a little game of solitaire that is quite easy, but not so easy as to be uninteresting. You can either rule out the squares on a sheet of cardboard or paper, or you can use a portion of your chessboard. I have shown numbered counters in the illustration so as to make the solution easy and intelligible to all, but chess pawns or draughts will serve just as well in practice. The puzzle is to remove all the counters except one, and this one that is left must be No. `1`. You remove a counter by jumping over another counter to the next space beyond, if that square is vacant, but you cannot make a leap in a diagonal direction. The following moves will make the play quite clear: `1-9`, `2-10`, `1-2`, and so on. Here `1` jumps over `9`, and you remove `9` from the board; then `2` jumps over `10`, and you remove `10`; then `1` jumps over `2`, and you remove `2`. Every move is thus a capture, until the last capture of all is made by No. `1`.

Sources:Topics:Combinatorics -> Game Theory Combinatorics -> Case Analysis / Checking Cases -> Processes / Procedures Puzzles and Rebuses

The puzzle is to remove all the counters except one, and this one that is left must be No. `1`. You remove a counter by jumping over another counter to the next space beyond, if that square is vacant, but you cannot make a leap in a diagonal direction. The following moves will make the play quite clear: `1-9`, `2-10`, `1-2`, and so on. Here `1` jumps over `9`, and you remove `9` from the board; then `2` jumps over `10`, and you remove `10`; then `1` jumps over `2`, and you remove `2`. Every move is thus a capture, until the last capture of all is made by No. `1`.

Sources:Topics:Combinatorics -> Game Theory Combinatorics -> Case Analysis / Checking Cases -> Processes / Procedures Puzzles and Rebuses- Amusements in Mathematics, Henry Ernest Dudeney Question 359