Puzzles and Rebuses

This is a general category for brain-teasers that require cleverness, lateral thinking, or pattern recognition. Rebuses are word puzzles using pictures, symbols, or letters to represent words or phrases. Math-related versions might involve numerical or operational clues hidden in a visual format.

Matchstick Puzzles Reconstruct the Exercise / Cryptarithmetic-

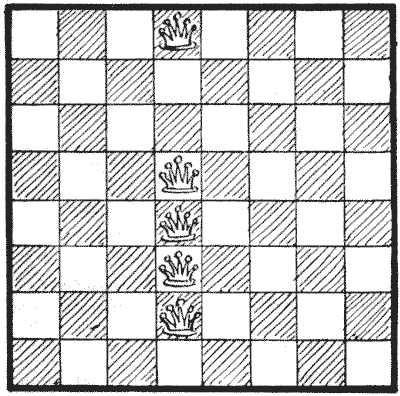

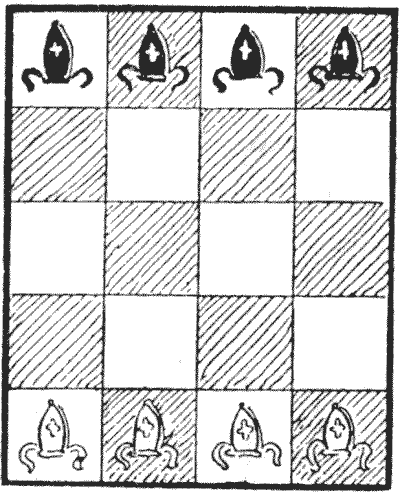

THE HAT-PEG PUZZLE

Here is a five-queen puzzle that I gave in a fanciful dress in `1897`. As the queens were there represented as hats on sixty-four pegs, I will keep to the title, "The Hat-Peg Puzzle." It will be seen that every square is occupied or attacked. The puzzle is to remove one queen to a different square so that still every square is occupied or attacked, then move a second queen under a similar condition, then a third queen, and finally a fourth queen. After the fourth move every square must be attacked or occupied, but no queen must then attack another. Of course, the moves need not be "queen moves;" you can move a queen to any part of the board.

Sources:Topics:Combinatorics -> Case Analysis / Checking Cases -> Processes / Procedures Puzzles and Rebuses

to a different square so that still every square is occupied or attacked, then move a second queen under a similar condition, then a third queen, and finally a fourth queen. After the fourth move every square must be attacked or occupied, but no queen must then attack another. Of course, the moves need not be "queen moves;" you can move a queen to any part of the board.

Sources:Topics:Combinatorics -> Case Analysis / Checking Cases -> Processes / Procedures Puzzles and Rebuses- Amusements in Mathematics, Henry Ernest Dudeney Question 315

-

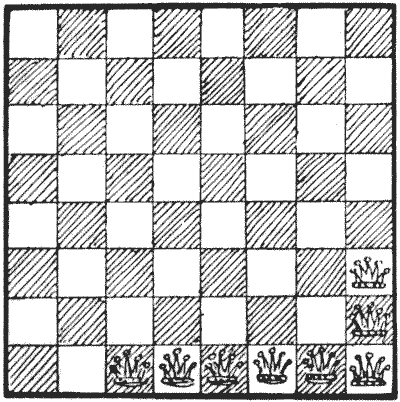

THE AMAZONS

This puzzle is based on one by Captain Turton. Remove three of the queens to other squares so that there shall be eleven squares on the board that are not attacked. The removal of the three queens need not be by "queen moves." You may take them up and place them anywhere. There is only one solution.

Sources:Topics:Puzzles and Rebuses

This puzzle is based on one by Captain Turton. Remove three of the queens to other squares so that there shall be eleven squares on the board that are not attacked. The removal of the three queens need not be by "queen moves." You may take them up and place them anywhere. There is only one solution.

Sources:Topics:Puzzles and Rebuses- Amusements in Mathematics, Henry Ernest Dudeney Question 316

-

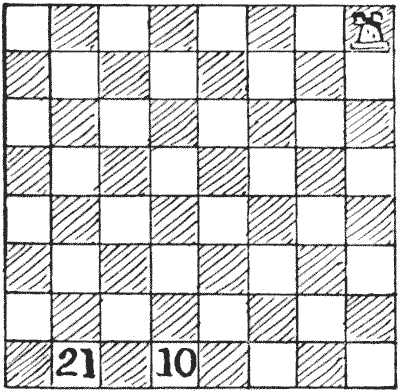

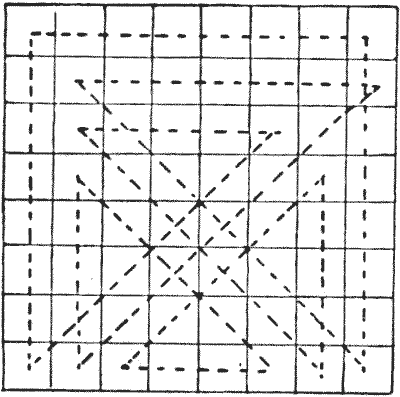

THE ROOK'S JOURNEY

This puzzle I call "The Rook's Journey," because the word "tour" (derived from a turner's wheel) implies that we return to the point from which we set out, and we do not do this in the present case. We should not be satisfied with a personally conducted holiday tour that ended by leaving us, say, in the middle of the Sahara. The rook here makes twenty-one moves, in the course of which journey it visits every square of the board once and only once, stopping at the square marked `10` at the end of its tenth move, and ending at the square marked `21`. Two consecutive moves cannot be made in the same direction—that is to say, you must make a turn after every move. Sources:Topics:Logic -> Reasoning / Logic Combinatorics -> Case Analysis / Checking Cases -> Processes / Procedures Combinatorics -> Combinatorial Geometry -> Grid Paper Geometry / Lattice Geometry Puzzles and Rebuses

Sources:Topics:Logic -> Reasoning / Logic Combinatorics -> Case Analysis / Checking Cases -> Processes / Procedures Combinatorics -> Combinatorial Geometry -> Grid Paper Geometry / Lattice Geometry Puzzles and Rebuses- Amusements in Mathematics, Henry Ernest Dudeney Question 321

-

AN EPISCOPAL VISITATION

The white squares on the chessboard represent the parishes of a diocese. Place the bishop on any square you like, and so contrive that (using the ordinary bishop's move of chess) he shall visit every one of his parishes in the fewest possible moves. Of course, all the parishes passed through on any move are regarded as "visited." You can visit any squares more than once, but you are not allowed to move twice between the same two adjoining squares. What are the fewest possible moves? The bishop need not end his visitation at the parish from which he first set out.Sources:Topics:Combinatorics -> Graph Theory Combinatorics -> Game Theory Combinatorics -> Colorings -> Chessboard Coloring Puzzles and Rebuses- Amusements in Mathematics, Henry Ernest Dudeney Question 325

-

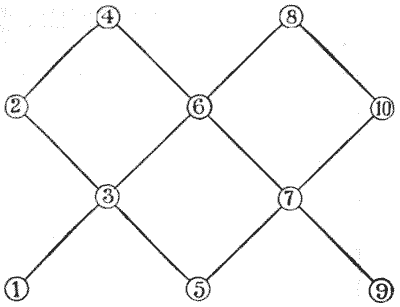

A NEW COUNTER PUZZLE

Here is a new puzzle with moving counters, or coins, that at first glance looks as if it must be absurdly simple. But it will be found quite a little perplexity. I give it in this place for a reason that I will explain when we come to the next puzzle. Copy the simple diagram, enlarged, on a sheet of paper; then place two white counters on the points `1` and `2`, and two red counters on `9` and `10`, The puzzle is to make the red and white change places. You may move the counters one at a time in any order you like, along the lines from point to point, with the only restriction that a red and a white counter may never stand at once on the same straight line. Thus the first move can only be from `1` or `2` to `3`, or from `9` or `10` to `7`. Sources:

Sources:

- Amusements in Mathematics, Henry Ernest Dudeney Question 326

-

A NEW BISHOP'S PUZZLE

This is quite a fascinating little puzzle. Place eight bishops (four black and four white) on the reduced chessboard, as shown in the illustration. The problem is to make the black bishops change places with the white ones, no bishop ever attacking another of the opposite colour. They must move alternately—first a white, then a black, then a white, and so on. When you have succeeded in doing it at all, try to find the fewest possible moves.

If you leave out the bishops standing on black squares, and only play on the white squares, you will discover my last puzzle turned on its side.

Sources:Topics:Combinatorics -> Combinatorial Geometry Combinatorics -> Graph Theory Combinatorics -> Game Theory Logic -> Reasoning / Logic Puzzles and Rebuses- Amusements in Mathematics, Henry Ernest Dudeney Question 327

-

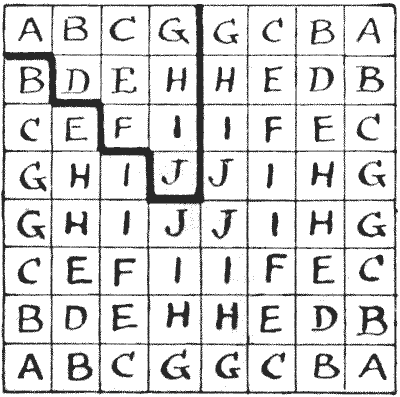

THE QUEEN'S TOUR

The puzzle of making a complete tour of the chessboard with the queen in the fewest possible moves (in which squares may be visited more than once) was first given by the late Sam Loyd in his Chess Strategy. But the solution shown below is the one he gave in American Chess-Nuts in `1868`. I have recorded at least six different solutions in the minimum number of moves—fourteen—but this one is the best of all, for reasons I will explain. If you will look at the lettered square you will understand that there are only ten really differently placed squares on a chessboard—those enclosed by a dark line—all the others are mere reversals or reflections. For example, every A is a corner square, and every J a central square. Consequently, as the solution shown has a turning-point at the enclosed D square, we can obtain a solution starting from and ending at any square marked D—by just turning the board about. Now, this scheme will give you a tour starting from any A, B, C, D, E, F, or H, while no other route that I know can be adapted to more than five different starting-points. There is no Queen's Tour in fourteen moves (remember a tour must be re-entrant) that may start from a G, I, or J. But we can have a non-re-entrant path over the whole board in fourteen moves, starting from any given square. Hence the following puzzle:—

If you will look at the lettered square you will understand that there are only ten really differently placed squares on a chessboard—those enclosed by a dark line—all the others are mere reversals or reflections. For example, every A is a corner square, and every J a central square. Consequently, as the solution shown has a turning-point at the enclosed D square, we can obtain a solution starting from and ending at any square marked D—by just turning the board about. Now, this scheme will give you a tour starting from any A, B, C, D, E, F, or H, while no other route that I know can be adapted to more than five different starting-points. There is no Queen's Tour in fourteen moves (remember a tour must be re-entrant) that may start from a G, I, or J. But we can have a non-re-entrant path over the whole board in fourteen moves, starting from any given square. Hence the following puzzle:—  Start from the J in the enclosed part of the lettered diagram and visit every square of the board in fourteen moves, ending wherever you like.

Sources:Topics:Combinatorics -> Combinatorial Geometry Combinatorics -> Game Theory Combinatorics -> Colorings -> Chessboard Coloring Puzzles and Rebuses

Start from the J in the enclosed part of the lettered diagram and visit every square of the board in fourteen moves, ending wherever you like.

Sources:Topics:Combinatorics -> Combinatorial Geometry Combinatorics -> Game Theory Combinatorics -> Colorings -> Chessboard Coloring Puzzles and Rebuses- Amusements in Mathematics, Henry Ernest Dudeney Question 328

-

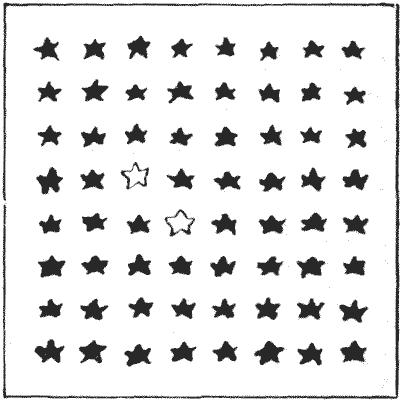

THE STAR PUZZLE

Put the point of your pencil on one of the white stars and (without ever lifting your pencil from the paper) strike out all the stars in fourteen continuous straight strokes, ending at the second white star. Your straight strokes may be in any direction you like, only every turning must be made on a star. There is no objection to striking out any star more than once.

In this case, where both your starting and ending squares are fixed inconveniently, you cannot obtain a solution by breaking a Queen's Tour, or in any other way by queen moves alone. But you are allowed to use oblique straight lines—such as from the upper white star direct to a corner star.

Sources:Topics:Combinatorics -> Combinatorial Geometry Combinatorics -> Graph Theory Logic -> Reasoning / Logic Puzzles and Rebuses- Amusements in Mathematics, Henry Ernest Dudeney Question 329

-

THE SCIENTIFIC SKATER

It will be seen that this skater has marked on the ice sixty-four points or stars, and he proposes to start from his present position near the corner and enter every one of the points in fourteen straight lines. How will he do it? Of course there is no objection to his passing over any point more than once, but his last straight stroke must bring him back to the position from which he started.

It is merely a matter of taking your pencil and starting from the spot on which the skater's foot is at present resting, and striking out all the stars in fourteen continuous straight lines, returning to the point from which you set out.

Sources:- Amusements in Mathematics, Henry Ernest Dudeney Question 331

-

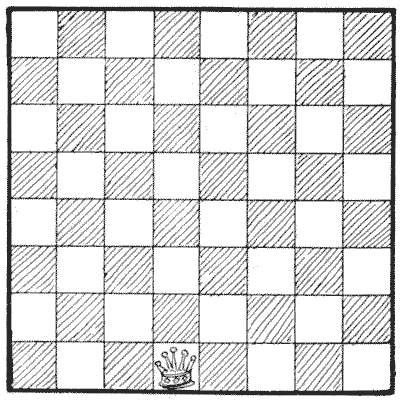

THE QUEEN'S JOURNEY

Place the queen on her own square, as shown in the illustration, and then try to discover the greatest distance that she can travel over the board in five queen's moves without passing over any square a second time. Mark the queen's path on the board, and note carefully also that she must never cross her own track. It seems simple enough, but the reader may find that he has tripped.

Sources:

Place the queen on her own square, as shown in the illustration, and then try to discover the greatest distance that she can travel over the board in five queen's moves without passing over any square a second time. Mark the queen's path on the board, and note carefully also that she must never cross her own track. It seems simple enough, but the reader may find that he has tripped.

Sources:

- Amusements in Mathematics, Henry Ernest Dudeney Question 333