Number Theory

Number Theory is a branch of mathematics concerned with the properties of integers. Topics include prime numbers, divisibility, congruences (modular arithmetic), Diophantine equations, and functions of integers. Questions often require analytical and creative thinking about numbers.

Prime Numbers Chinese Remainder Theorem Modular Arithmetic / Remainder Arithmetic Greatest Common Divisor (GCD) and Least Common Multiple (LCM) Triangular Numbers Division-

THE NINE TREASURE BOXES

The following puzzle will illustrate the importance on occasions of being able to fix the minimum and maximum limits of a required number. This can very frequently be done. For example, it has not yet been ascertained in how many different ways the knight's tour can be performed on the chess board; but we know that it is fewer than the number of combinations of `168` things taken `63` at a time and is greater than `31,054,144`—for the latter is the number of routes of a particular type. Or, to take a more familiar case, if you ask a man how many coins he has in his pocket, he may tell you that he has not the slightest idea. But on further questioning you will get out of him some such statement as the following: "Yes, I am positive that I have more than three coins, and equally certain that there are not so many as twenty-five." Now, the knowledge that a certain number lies between `2` and `12` in my puzzle will enable the solver to find the exact answer; without that information there would be an infinite number of answers, from which it would be impossible to select the correct one.

This is another puzzle received from my friend Don Manuel Rodriguez, the cranky miser of New Castile. On New Year's Eve in `1879` he showed me nine treasure boxes, and after informing me that every box contained a square number of golden doubloons, and that the difference between the contents of A and B was the same as between B and C, D and E, E and F, G and H, or H and I, he requested me to tell him the number of coins in every one of the boxes. At first I thought this was impossible, as there would be an infinite number of different answers, but on consideration I found that this was not the case. I discovered that while every box contained coins, the contents of A, B, C increased in weight in alphabetical order; so did D, E, F; and so did G, H, I; but D or E need not be heavier than C, nor G or H heavier than F. It was also perfectly certain that box A could not contain more than a dozen coins at the outside; there might not be half that number, but I was positive that there were not more than twelve. With this knowledge I was able to arrive at the correct answer.

In short, we have to discover nine square numbers such that A, B, C; and D, E, F; and G, H, I are three groups in arithmetical progression, the common difference being the same in each group, and A being less than `12`. How many doubloons were there in every one of the nine boxes?

Sources:Topics:Number Theory Algebra -> Sequences -> Arithmetic Progression / Arithmetic Sequence Algebra -> Equations -> Diophantine Equations- Amusements in Mathematics, Henry Ernest Dudeney Question 132

-

THE FIVE BRIGANDS

The five Spanish brigands, Alfonso, Benito, Carlos, Diego, and Esteban, were counting their spoils after a raid, when it was found that they had captured altogether exactly `200` doubloons. One of the band pointed out that if Alfonso had twelve times as much, Benito three times as much, Carlos the same amount, Diego half as much, and Esteban one-third as much, they would still have altogether just `200` doubloons. How many doubloons had each?

There are a good many equally correct answers to this question. Here is one of them:

A 6 × 12 = 72 B 12 × 3 = 36 C 17 × 1 = 17 D 120 × ½ = 60 E 45 × 1/3 = 15 200 200 The puzzle is to discover exactly how many different answers there are, it being understood that every man had something and that there is to be no fractional money—only doubloons in every case.

This problem, worded somewhat differently, was propounded by Tartaglia (died `1559`), and he flattered himself that he had found one solution; but a French mathematician of note (M.A. Labosne), in a recent work, says that his readers will be astonished when he assures them that there are `6,639` different correct answers to the question. Is this so? How many answers are there?

Sources:Topics:Number Theory Arithmetic Algebra -> Word Problems Algebra -> Sequences -> Arithmetic Progression / Arithmetic Sequence Combinatorics -> Case Analysis / Checking Cases -> Processes / Procedures Algebra -> Equations -> Diophantine Equations- Amusements in Mathematics, Henry Ernest Dudeney Question 133

-

THE STONEMASON'S PROBLEM

A stonemason once had a large number of cubic blocks of stone in his yard, all of exactly the same size. He had some very fanciful little ways, and one of his queer notions was to keep these blocks piled in cubical heaps, no two heaps containing the same number of blocks. He had discovered for himself (a fact that is well known to mathematicians) that if he took all the blocks contained in any number of heaps in regular order, beginning with the single cube, he could always arrange those on the ground so as to form a perfect square. This will be clear to the reader, because one block is a square, `1+8 = 9` is a square, `1+8+27=36` is a square, `1+8+27+64=100` is a square, and so on. In fact, the sum of any number of consecutive cubes, beginning always with `1`, is in every case a square number.

One day a gentleman entered the mason's yard and offered him a certain price if he would supply him with a consecutive number of these cubical heaps which should contain altogether a number of blocks that could be laid out to form a square, but the buyer insisted on more than three heaps and declined to take the single block because it contained a flaw. What was the smallest possible number of blocks of stone that the mason had to supply?

Sources:- Amusements in Mathematics, Henry Ernest Dudeney Question 135

-

MRS. SMILEY'S CHRISTMAS PRESENT

Mrs. Smiley's expression of pleasure was sincere when her six granddaughters sent to her, as a Christmas present, a very pretty patchwork quilt, which they had made with their own hands. It was constructed of square pieces of silk material, all of one size, and as they made a large quilt with fourteen of these little squares on each side, it is obvious that just `196` pieces had been stitched into it. Now, the six granddaughters each contributed a part of the work in the form of a perfect square (all six portions being different in size), but in order to join them up to form the square quilt it was necessary that the work of one girl should be unpicked into three separate pieces. Can you show how the joins might have been made? Of course, no portion can be turned over. Sources:Topics:Geometry Number Theory Arithmetic Combinatorics -> Combinatorial Geometry -> Cut a Shape / Dissection Problems

Sources:Topics:Geometry Number Theory Arithmetic Combinatorics -> Combinatorial Geometry -> Cut a Shape / Dissection Problems- Amusements in Mathematics, Henry Ernest Dudeney Question 172

-

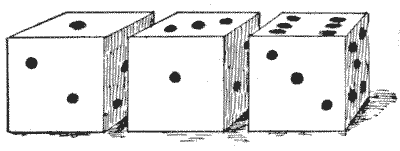

A TRICK WITH DICE

Here is a neat little trick with three dice. I ask you to throw the dice without my seeing them. Then I tell you to multiply the points of the first die by `2` and add `5`; then multiply the result by `5` and add the points of the second die; then multiply the result by `10` and add the points of the third die. You then give me the total, and I can at once tell you the points thrown with the three dice. How do I do it? As an example, if you threw `1, 3`, and `6`, as in the illustration, the result you would give me would be `386`, from which I could at once say what you had thrown.

Sources:

Here is a neat little trick with three dice. I ask you to throw the dice without my seeing them. Then I tell you to multiply the points of the first die by `2` and add `5`; then multiply the result by `5` and add the points of the second die; then multiply the result by `10` and add the points of the third die. You then give me the total, and I can at once tell you the points thrown with the three dice. How do I do it? As an example, if you threw `1, 3`, and `6`, as in the illustration, the result you would give me would be `386`, from which I could at once say what you had thrown.

Sources:

- Amusements in Mathematics, Henry Ernest Dudeney Question 386

-

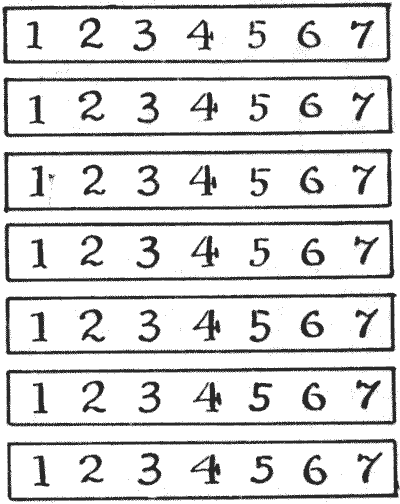

THE MAGIC STRIPS

I happened to have lying on my table a number of strips of cardboard, with numbers printed on them from `1` upwards in numerical order. The idea suddenly came to me, as ideas have a way of unexpectedly coming, to make a little puzzle of this. I wonder whether many readers will arrive at the same solution that I did.

Take seven strips of cardboard and lay them together as above. Then write on each of them the numbers `1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7`, as shown, so that the numbers shall form seven rows and seven columns.

Now, the puzzle is to cut these strips into the fewest possible pieces so that they may be placed together and form a magic square, the seven rows, seven columns, and two diagonals adding up the same number. No figures may be turned upside down or placed on their sides—that is, all the strips must lie in their original direction.

Of course you could cut each strip into seven separate pieces, each piece containing a number, and the puzzle would then be very easy, but I need hardly say that forty-nine pieces is a long way from being the fewest possible.

Sources:- Amusements in Mathematics, Henry Ernest Dudeney Question 400

-

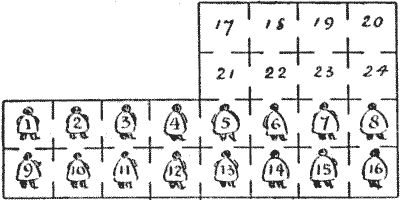

THE SIBERIAN DUNGEONS

The above is a trustworthy plan of a certain Russian prison in Siberia. All the cells are numbered, and the prisoners are numbered the same as the cells they occupy. The prison diet is so fattening that these political prisoners are in perpetual fear lest, should their pardon arrive, they might not be able to squeeze themselves through the narrow doorways and get out. And of course it would be an unreasonable thing to ask any government to pull down the walls of a prison just to liberate the prisoners, however innocent they might be. Therefore these men take all the healthy exercise they can in order to retard their increasing obesity, and one of their recreations will serve to furnish us with the following puzzle.

Show, in the fewest possible moves, how the sixteen men may form themselves into a magic square, so that the numbers on their backs shall add up the same in each of the four columns, four rows, and two diagonals without two prisoners having been at any time in the same cell together. I had better say, for the information of those who have not yet been made acquainted with these places, that it is a peculiarity of prisons that you are not allowed to go outside their walls. Any prisoner may go any distance that is possible in a single move.

Sources:Topics:Number Theory Combinatorics -> Case Analysis / Checking Cases -> Processes / Procedures Combinatorics -> Number Tables- Amusements in Mathematics, Henry Ernest Dudeney Question 404

-

Question

Given a three-digit prime number with all its digits distinct. It is known that its last digit is equal to the sum of the other two digits. Find all the possibilities for the last digit of this number.

Sources:Topics:Number Theory -> Prime Numbers Number Theory -> Modular Arithmetic / Remainder Arithmetic -> Divisibility Rules -> Divisibility Rules by 2, 4, and 8 Number Theory -> Modular Arithmetic / Remainder Arithmetic -> Divisibility Rules -> Divisibility Rules by 3 and 9 Logic -> Reasoning / Logic Combinatorics -> Case Analysis / Checking Cases -> Processes / Procedures -

Question

Find all pairs of prime numbers whose difference is `17`.

Sources: -

Question

Given the polynomial `P(n)=n^2+n+41`. Is it true that this polynomial yields prime numbers for all natural numbers `n`?

Sources: